The OctoPost: Mining for Squid and Plant-Based Octopus

Happy Cephalopod Week, Science Friday’s annual celebration of our suckered pals! Several friends (thank you, K and Cherilyn) tipped me off that Monarchs of the Sea was featured in the Cephalopod Week newsletter:

Check out the discussion guide!

Science Friday was one of the first media outlets to endorse my writing, back in 2017 when they chose Squid Empire (the first edition of Monarchs of the Sea) as one of the best science books of the year. Since then, I’ve been honored and delighted to join many wonderful SciFri people for many splendid events (e.g., Book Club). Love you, Science Friday!

Cephalopod News

One of the most fascinating facts that I learned while researching Squid Empire/Monarchs of the Sea was that squid “evolved themselves out of the fossil record.”

This is somewhat true of all soft-bodied cephalopods. After losing their shells, they didn’t have many hard parts left, and soft tissue rarely fossilizes. Squid, however, took it a step further. To provide the same buoyancy that once came from gas-filled shells, they began filling their bodies with lightweight ammonia, which changed their pH after death such that they were even less likely to fossilize.

As a result, scientists had very little idea when modern squid first evolved, where they lived, or how abundant they were. People knew that some early squid swam around Cretaceous seas, but figured that the group didn’t really take off until after the end-Cretaceous extinction (the one that nixed the dinosaurs).

But paleontologists are nothing if not persistent. They kept looking for squid fossils, and this year Yasuhiro Iba and colleagues published results from a technique called “digital fossil mining” that revealed some of the few hard parts squid leave behind—their beaks.

Although beaks are hard, they’re also fragile, and typically destroyed by conventional fossil mining with picks and chisels. Digital fossil mining, by contrast, involves grinding off a thin layer of rock, taking a photo, then grinding off another thin layer, then taking another photo, and so on all through the rock. Finally, all the photos are stacked to create a 3D model of the rock’s contents.

With this technique, Iba and colleagues found hundreds of beaks from dozens of squid in 100-million-year old rocks. This suggests that squid proliferated smack in the middle of the Cretaceous, when Giganotosaurus and Argentinosaurus were still tromping around happily on land. In the sea, squid were growing as big as fish and even more abundant—”a larger biomass than any other coexisting nektonic [swimming] organism.”

In other words, squid were shaping marine ecosystems before primates were even a twinkle in the eyes of our mammalian ancestors.

Meanwhile in other cephalo-news, amidst of turmoil in octopus fishing and farming arrives this interesting tidbit: an Austrian company developed plant-based octopus arms that let people “enjoy the culinary experience of octopus, without any of the ethical or environmental downsides.”

As a lifelong vegetarian, I’m not personally drawn to consume hyper-realistic fake meat, but I think it would be cool if octopus-eaters find this a compelling substitute! What do you think?

My News

October 10, 2025: I’ll be a panelist on "The Power of Children's Nonfiction" at the California Reading Association Conference (virtual)

October 25-31: I’ll be at the Cephalopod International Advisory Council in Okinawa, Japan!

Did you know I have an online shop where you can buy nerdy t-shirts and cards that I designed? It’s true! Some lovely person recently purchased a squid size comparison shirt, which reminded me that they exist. Just in time for Squidtember!

Funny Pages

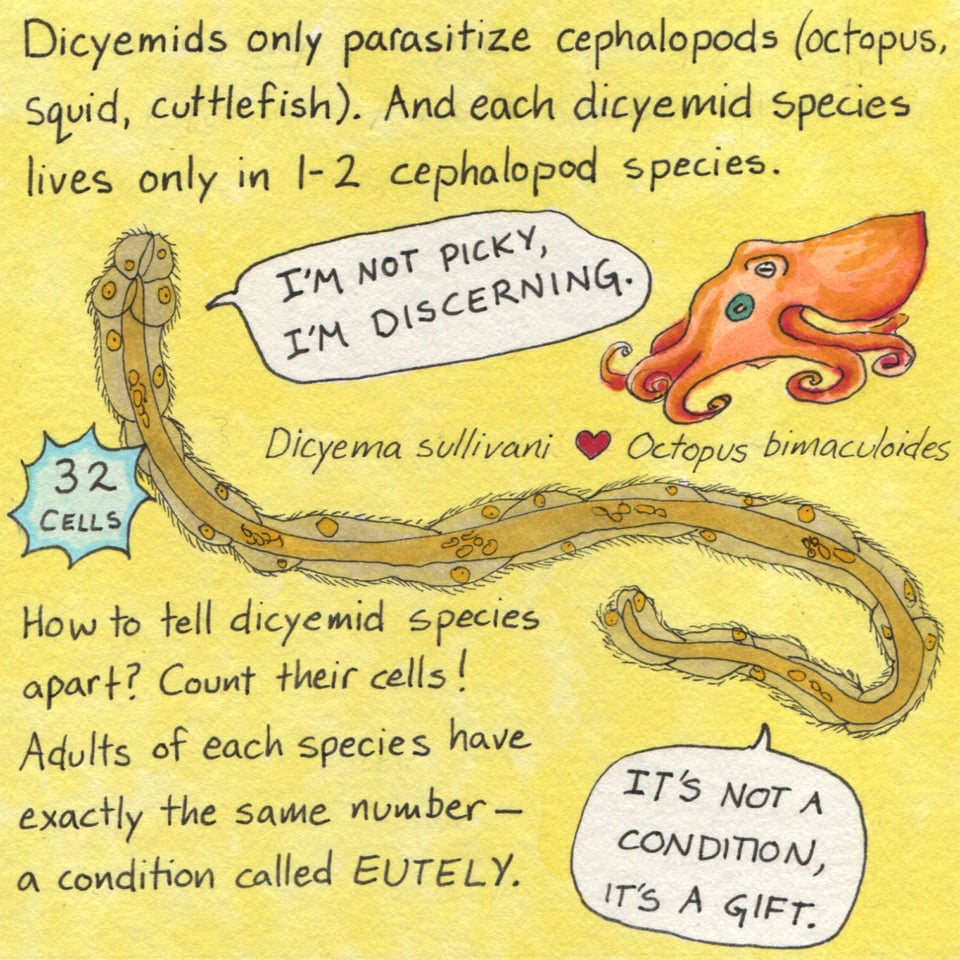

In May I shared the title page for a comic about my favorite under-appreciated parasitic worms (yes, that is a large enough category from which to choose a favorite). I have finally produced the first panel.

-

Fascinating entries! Digital paleontology sounds like it could also reveal more about animals with cartilage skeletons (Megalodon, Dunkleosteus) where only small bits of the body with high density may become fossils.

Add a comment: