Oceans of Power and a Tincture of Reproof

Readers of this newsletter know that my favored subject is that which we are often fooled into believing will be boring. I am drawn to boring things because they are so often so significant. I am also drawn to boring things because I am suspicious of excitement. I know, I know: hard to believe.

My first book explored how life insurers created powerful means for describing human lives and justifying inequality in society. While many of the practices of the insurers disgusted me, their larger project of sharing risk seemed to me to be worth more attention. I don't much like the measurement of "risk" in private institutions, but I believe a great deal in spreading risk through state-sponsored systems like Social Security or Medicare. The same goes for my second book, on the census, which in its execution has sometimes been a tool for doing much harm, and yet which is also fundamental to the project of building a mass democracy.

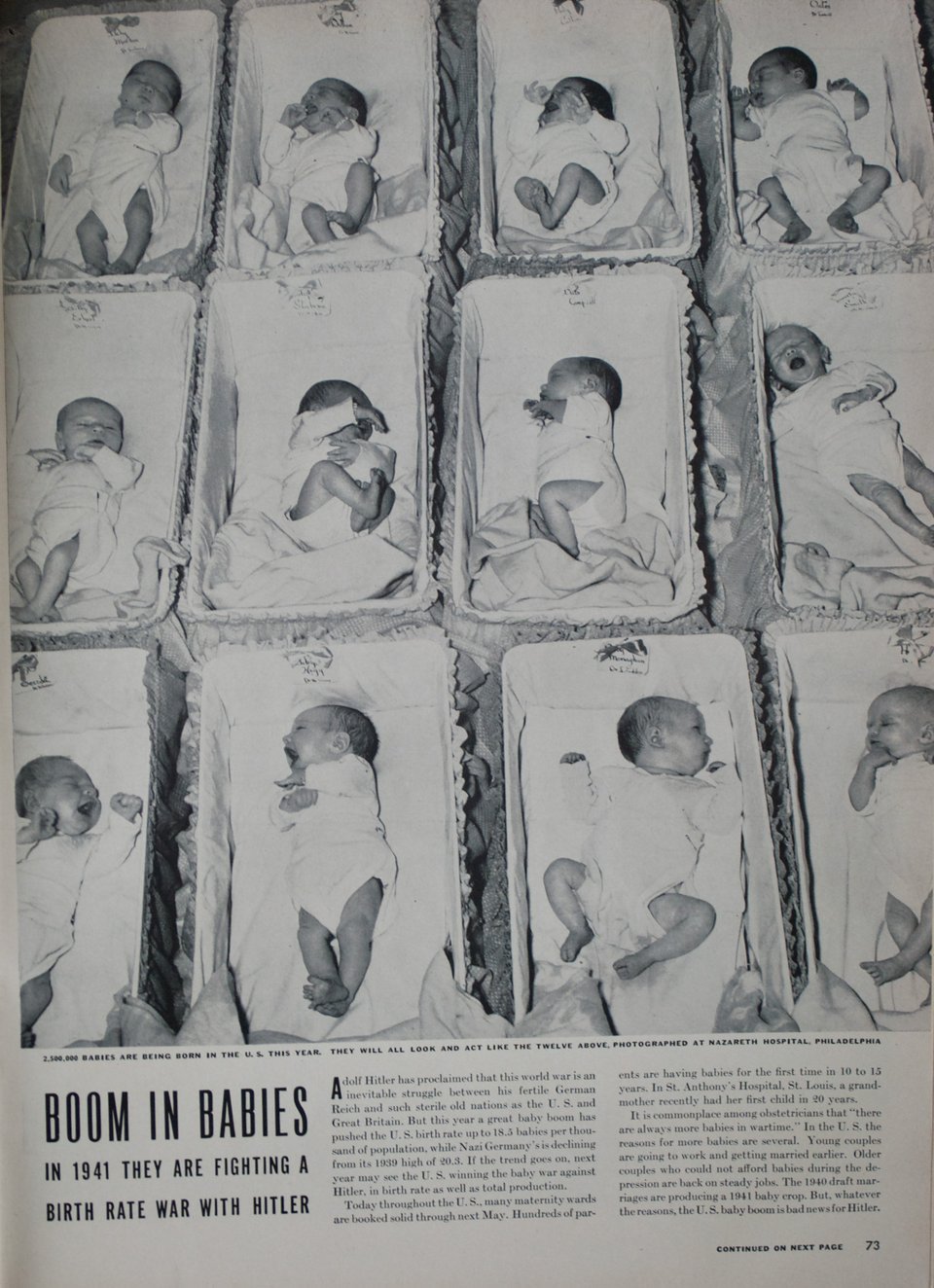

In between those books, I toyed with writing a history of the idea of the "baby boom generation." I wrote this article, called "Generation Crisis: How Population Research Defined the Baby Boomers." (Shoot me a note if you're interested and can't access a copy.) But I gave up on writing the book because it was too exciting. I really, really, really do not think it is helpful to talk about generations. But even if I wrote a book offering a blistering critique of the generational concept, I feared that readers would come away more invested in the idea of the Baby Boomers, whether they loved them or hated them. So, I just didn't write that book.

In this issue of the newsletter, I consider some truly excellent writers who made a different choice. Stay tuned for Ralph Waldo Emerson, Robert Caro, and Jack London.

I guess I am wondering if I made the right choice, and if I should stick to my suspicions in the future. What do you think?

I imagine Ralph Waldo Emerson (Waldo, to this friends) entering a lecture hall in the mid-nineteenth century. His listeners packed tightly against one another, the better to fend off the winter cold. The old sat alongside the young, "bald heads and flowing transcendental locks" abutting "misanthropists and lovers." This would have been the sixth day and the sixth lecture on this leg of a five-year-long tour for Emerson. Those in the audience who had stuck it out this far would have already heard the great man Emerson explain PHILOSOPHY by explaining Plato, and MYSTICISM with the (now forgotten) Emanuel Swedenborg, and SKEPTICISM through Montaigne, and POETRY via Shakespeare. The critic Andrew Delbanco reports the crowds were "rapt and grateful," and so we can presume that most in fact stuck it out to the end. Recall that there was no internet to distract them. And so on the final day of the lecture series, Emerson turned his audiences' attention to the "man of the world," the practical man, the person who could GET THINGS DONE. His subject was Napoleon Bonaparte, a subject he had every reason to believe would fascinate the entire auditorium.

As Emerson said:

Emerson, in the late 1840s, could presume that his audience already knew a lot about Napoleon, that they were likely among the "million readers of anecdotes or memoirs or lives" of the great man. People in the mid-nineteenth century US read about Napoleon for many reasons, and yet it seems that many treated him as a hero. The great social thinker, activist, and feminist of the turn of the twentieth century, Jane Addams, also studied Napoleon's life. According to her biographer, Louise Knight, Addams spent much of her childhood reading from her father's library. He paid her a nickel for every book she read and discussed with him. According to Knight, "Great men such as Washington, Jefferson, Franklin, Cromwell, and Napoleon were heavily featured." Napoleon sat alongside the American founders. These were the lives that Addams would later try to emulate. When she founded the settlement project Hull House in Chicago, she was seeking a way to overcome the limits society put on her because of her sex. She too could get things done. Knight says that the biographies of great men taught Addams that "her gender was irrelevant to heroic dreams."

Emerson's or Addams' contemporaries read about the life of Napoleon the way that people today read biographies of Steve Jobs or Elon Musk, and, well,...Napoleon, I guess. Just perusing the recent releases, I see multiple Napoleon biographies out in English in the last decade, as well as books that treat the great warrior as a key to leadership or business success. And then, of course, we all recall that Ridley Scott made waves with a major motion picture, Napoleon, out just last year. (Most importantly for my own intellectual development, Napoleon ranked an appearance as a true GREAT MAN in Bill and Ted's Excellent Adventure, one of the foundational texts of my youth.)

And Napoleon lives on today very prominently in the tech world too. Napoleon's monumental military catastrophes lost the battle and the war two centuries ago, but they conquered the data visualization world's imagination, through this iconic nineteenth century exemplar:

In the wonderful new website Data By Design, Lauren Klein says of the chart: "For if the story told in the chart is one of hubris and of the horrors of war, the story told about the chart is nothing short of heroic." Prepared by the engineer Charles Minard in 1869, the "Carte Figurative" recounts Napoleon's 1812-1813 campaign to Moscow. The advance of Napoleon's French forces proceeds left to right, west to east in a peach hued column, and then the terrible retreat from Russia, in black reveals the army's decimation from right to left, while a graph beneath the chart shows plummeting temperatures freezing the fleeing troops. The chart has become iconic (in no small part thanks to Edward Tufte.) It is not only beautiful, but as Klein sees so clearly, its sheer scale and grandeur awes the viewer, even when the subject is such an unmitigated defeat and disaster.

Emerson took these same ingredients: amazing ambition and unparalleled power, blended with the undeniable fact of failure, and he brewed his own fascinating potion for listeners twenty years earlier. Published in 1849, in a book called Representative Men, his lecture leans into Napoleon's myth, making him at once a superhuman and an everyman.

According to Emerson,

He controlled France, because he literally embodied its ambitions, and the French people embodied his:

Emerson doesn't even seem to mean this as a metaphor. Rather, he sees in Napoleon an accomplishment of the latent possibility that one man can draw on his connections to those around him and so attain otherwise impossible capacities:

My favorite line is this one:

What was modernity in the mid-nineteenth century? It was the newspapers. Napoleon and the newspapers, like Jobs and the smartphone, or Musk and the corporate rocketship...

As the thoroughly modern representative of the striving middle classes, Napoleon possesses extraordinary capacities:

He doesn't just fight and win on the battlefields. He remakes the world. "He builds the road."

Napoleon accomplished this, according to Emerson, by renouncing "once for all, sentiments and affections":

To hear Emerson tell it, Napoleon performed miracles by modern means:

And in what is easily the most poetic homage to logistical mastery ever written:

In sum, Emerson deemed Napoleon "the agent or attorney of the middle class of modern society;" (what Emerson's contemporary, Karl Marx, might have called the bannerman of the bourgeoisie):

I have, over the last fourteen years, assigned this lecture to students many times. I give it to them because it is fascinating, and also because it is confounding. As I seek to get them to think about how and why an author might lead an audience in a strange or unexpected direction, there is no better text, nor a more frustrating one. Because the reader sticks with Emerson for 30 pages; we are pummeled by story upon story and assertion atop assertion of Napoleon's greatness; then, in the last five pages, Emerson takes it all away from us, and makes the sudden forceful case for the opposite of everything we've just been reading.

Early in the lecture, Emerson explained that Napoleon "wrought, in common with that great class he represented, for power and wealth." His advantage was always that he cared nothing for feelings or morals: "all the sentiments which embarrass men's pursuit of these objects, he set aside." And yet, it is still shocking when Emerson turns on Napoleon with full force and asks us to sit with exactly what it meant to be untroubled by sentiment:

He would steal, slander, assassinate, drown and poison, as his interest dictated.

For thirty pages, Napoleon surpassed all in his abilities and powers.

For the final five pages, he is revealed to surpass all in sociopathy.

What does it all mean?

IMMENSE ARMIES.

BURNED CITIES.

SQUANDERED TREASURES.

IMMOLATED MILLIONS.

no result.

...........no result?!

Here is a recapitulation of the entire lecture: an accounting of unbelievable effects, and then somehow the assertion that NONE OF IT MATTERED.

My students have almost universally found this essay frustrating. Why, they ask, did we read about Napoleon for 30 pages, only to hear that his power had "no result"? Emerson's contemporary, Thomas Carlyle, the Scottish essayist and the writer of his own book of essays about "Great Men" shared their frustration. While he praised the lectures generally, he lamented what critic Andrew Delbanco reports to be their "fickleness." Delbanco's 1996 introduction to Representative Men quotes Carlyle: "I generally dissented a little about the end of all these Essays; which was notable, and not without instructive interest to me, as I had so lustily shouted, 'Hear, Hear!' all the way from the beginning up to that stage." My students were unlikely to be chanting "Hear! Hear!" as they read, but they widely shared the dissent.

Maybe you're wondering why I just dragged you, my dear readers, through a similar experience in this newsletter. Didn't torturing my students with this exercise satiate my cruel academic sadism?

Not at all. And, in fact, I am not nearly done with you.

The thing is that I think you all willingly subject yourself to this sort of perverse prose all the time. Emerson appealed to the allure of naked power so that he could condemn it: his listeners might have seen in Napoleon a great achiever who they wanted to either emulate or exalt, and Emerson lured the multitudes in by giving them the spectacle of imperial ascent before plunging them into the utter hopelessness of power devoid of spirit or sentiment. If the criticism lands and sticks, the gambit succeeds. Yet what if Emerson's disdain is more like the salt in the stew? What if a bit of moral outrage simply makes the pleasure of worshipping the powerful a bit more palatable?

This year we celebrate the 50th anniversary of Robert Caro's masterpiece, The Power Broker: Robert Moses and the Fall of New York. Dan Cohen described the book beautifully in his own recent 50th anniversary reflection. He wrote:

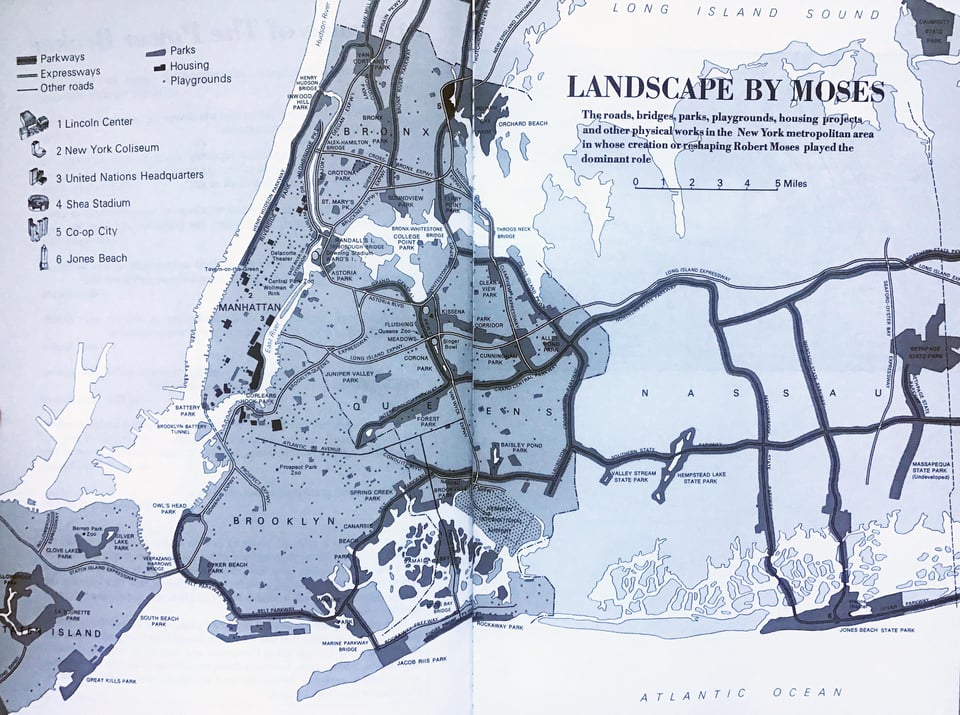

The Power Broker is a history of New York and a biography of Moses, who so irrevocably altered the region through parks, playgrounds, housing, bridges, and especially his beloved roadways, that a journey across New York is a passage through his realized dreams. The book is also a vivid nightmare: an unflinching account of the loss of neighborhoods to pavement, good government idealism to corrupt dealing, the possibility of integration to the reality of segregation.

A book filled with dreams, which are eventually revealed to be nightmares.

Dear reader, do you see the kind of story we're talking about it?

Do you recognize it?

Cohen explains that the book's primary subject is "the allure of power and how it persists." He laments how little we've learned from exposure to those lessons. But what if the most effective way to get people to understand the dangers of power is to bathe them in its allure? As Cohen points out, the way that Moses himself gained power was by immersing himself in the details and minutiae that others overlooked.

Cohen reads a clear tension in Caro's story. I do too. It seems, often, as though Caro admires his supposed villain: "The Power Broker may be a brutal indictment of Moses, but Caro also beams with admiration — and invites the reader to stand in awe, as well — at what Moses was able to accomplish, and with such speed." Does Caro admire Moses? Did Emerson admire Napoleon? Or is this part of the genre, the tactic?

A few months ago, a Colgate colleague told me about a special podcast series from 99% Invisible that is reading and discussing Caro's 1,200 page book over the course the entirety of 2024. The July episode (a real banger about the power of the state-created public "authority" and featuring a cameo by rumored vice-presidential candidate Pete Buttigieg) saw the hosts, Roman Mars and Elliott Kalan, breach the book's second half. Mars and Kalan read the text closely and admiringly, summarizing it for those who haven't read, while generally expressing glee at Moses's accomplishments while turning to gallows humor as they mordantly survey the so-called master builder's growing list of misdeeds. They know the book well and pick up on Caro's writerly ticks, from the unaccountably effective way he uses long lists of roads or projects, to the way he cannot help but praise a historical character who likes research in the library as much as Caro evidently enjoys it himself. Yet they do not acknowledge the dangerous bargain undergirding the book, probably because their podcast depends on it as well.

In fact, I have yet to see anyone point out the Emersonian genius of The Power Broker, even though I think it explains a significant part of the book's success. Robert Moses emerges for the story as the most powerful of people, or even as more powerful than a person can be. Readers (like me) desire proximity to his power, his greatness. They wallow in his filthy successes and murky compromises, marveling at the things he got done. Then they read that it was terrible---so terrible, and perhaps they learn a lesson, or maybe they are merely cleansed of the guilt of their voyeuristic pleasure.

The 99% Invisible folks are 100% right about Caro and lists. Take this example, in which we learn about an annus mirabilis in Robert Moses's early career:

By the end of the summer of 1928, the watershed properties off Merrick Road had been filled with bathhouses, baseball fields and bridle paths. Picnic areas with thousands of tables sat under their trees. Slides, swings and jungle gyms spotted their clearings. Their lakes were decorated with floats, diving boards, sliding ponds, rowboats and canoes. Heckscher State Park contained miles of paved roads for cars and dirt roads for horseback riders, acres of athletic fields, bathhouses holding five thousand lockers, a boardwalk, a bathing pavilion with restaurants and snack bars, an inland canal for row-boating, and a marina at which sailboats could be moored. There were more picnic areas, more campsites at Sunken Meadow, Wildwood, Orient Beach, Montauk Point and Hither Hills state parks. On Jones Beach, two years before a desolate sand bar, there stood now, awaiting only the finishing touches that would be added in 1929, a bathhouse like a medieval castle, a water tower like the campanile of Venice, a boardwalk, a restaurant and parking fields that held ten thousand cards each. In the history of public works in America, it is probable that never had so much been built so fast. (238)

Riding along in Caro's lists we find alliteration: "bathhouses, baseball fields, and bridle paths"; mixed with near-rhyming: "slides, swings, and jungle gyms." And it is all meant to convey both the beauty of the result and the unprecedented scope of Moses's achievement. In two years, "a desolate sand bar" blossomed. Like Napoleon, Moses somehow made matter and people bend to his will. "In the history of public works in America, it is probable that never had so much been built so fast." Like Napoleon, if Moses could think of a thing, he could do it: "Robert Moses had dreamed a dream immense in scope. By the end of the summer of 1928, the dream...was either reality or well on its way to becoming reality."(240)

The reader learns, early on in the book, that Moses's legacy is muddy, murky, or maybe even mostly malevolent. The book's subtitle pairs Robert Moses with "the Fall of New York." Yet it's hard to maintain one's disapproval of Moses in the face of his extraordinary powers and abilities.

We as readers are 800 pages into this book, 2/3s of the way, when we reach the point where Caro makes his Emersonian renunciation most completely.

It begins by building up Moses, making him something more than a man, making him more than an entire era, making him a "force of nature":

To compare the works of Robert Moses to the works of man, one has to compare them not to the works of individual men but to the combined total work of an era. The yardstick by which his public housing and Title I feats can best be measured, for example, is the Age of Skyscrapers, which reared up the great masses of stone and steel and concrete over Manhattan in quantity comparable to his. The yardstick by which the influence of his highways can be gauged is the Age of Railroads. But Robert Moses did not build only housing projects and highways. Robert Moses built parks and playgrounds and beaches and parking lots and cultural centers and civic centers and a United Nations Building and a Shea Stadium and a Coliseum and swept away neighborhoods to clear the way for a Lincoln Center and the mid-city campuses of four separate universities. He was a shaper not of sections of a city but of a city. He was, for the greatest city in the Western world, the city shaper, the only city shaper. In sheer physical impact on New York and the entire New York metropolitan region, he is comparable not to the works of any man or group of men or even generations of men. In the shaping of New York, Robert Moses was comparable only to some elemental force of nature. (830)

The maps that open the book convey the majesty of Moses as this "elemental" figure, as a "city shaper" over and over and over.

Having elevated Moses above all other mortals, Caro makes his most sustained indictment of the efforts of this superhuman actor.

But if in the shaping of New York Robert Moses was an elemental force, he was also a blind force: blind and deaf, blind and deaf to reason, to argument, to new ideas, to any ideas except his own. (830)

And he continues his indictment in the succeeding paragraphs:

He possessed vision in a measure possessed by few men. But he wouldn’t use it. (830)

No rules, not even the most innocuous, could apply to him. (831)

As he was above rules, he was above the law. He had always felt himself above it, ignored its spirit whenever possible, but now there was a new depth to this feeling, a new intensity to this particular manifestation of arrogance. (831)

Power, without morality, doomed Napoleon to meaningless conquest. Power, without democracy, rationality, or law, doomed Moses to destroy a city.

(Caro's eventual argument is that Moses, with one hand, built sprawling highways as monuments to the automobile. But with the other hand he underfunded public transit, destroyed neighborhoods, and corrupted political systems by creating public "authorities" that he alone controlled.)

If the fable of Moses's power is still widely known, thanks to Caro's book, then a similar fictional story from a century ago has been almost entirely forgotten. Up until about a year ago, I had never even heard of Jack London's Burning Daylight, and I certainly had never read it. But then Robin Sloan hinted to me that a character in his new novel Moonbound (available wherever you buy books!) was based on an indelible image of Burning Daylight's larger-than-life title character, whose given name was Elam Harnish, but who was universally known for the way he'd rouse a camp of Alaskan gold prospectors by hollering that he and his fellow miners were "burning daylight!"

So I picked up London's novel from 1910 and indeed I succumbed to its muscular, propulsive narrative. The novel had been written to be serialized, with each chapter printed separately in the New York Herald. That makes it read a lot like a TV series, where each chapter is an episode, complete unto itself while ending with cliffhangers and unresolved mysteries aimed at getting readers to shell out another nickel to purchase the Herald when the next chapter dropped. (I'm assuming the stories came out in the Sunday papers, which were usually more expensive than the ordinary penny dailies. I have tried, but so far failed to find the originals.)

The book opens with a contest on a quiet night in Circle City, Alaska. Daylight bets his entire fortune of $40,000 on a hand of cards in an epic, glorious round of poker: "it was the moment of moments that men wait weeks for in a poker game." He contests bravely until the final draw falls against him. I would just roll up in a ball at that point. Actually: I would have never bet everything in the first place on a hand of cards. But Daylight is different.

He basically just shrugs the loss off and determines he will replenish his nearly empty purse by delivering the mail by dogsled across miles of harrowing, freezing terrain--and he is determined to accomplish the task in record time, because he can.

But first, Jack London makes clear that for Daylight, all life is a competition or ought to be made into one. It is hard not to root for him as he keeps winning, even or especially when facing seemingly impossible odds. And it's hard not to root for him when he loses, often spectacularly, and just gets right back up to gamble again.

Having lightened his purse of gold dust until it weighed nearly nothing at all, Burning Daylight followed his poker disaster with contests of strength: "At six the next morning, scorching with whiskey, yet ever himself, he stood at the bar putting every man's hand down." When Daylight bested at arm wrestling even the two biggest men in the camp, a massive French Canadian and his distinctly nordic business partner, the losers cried foul. Daylight wagered his final grains of gold on a test of sheer muscular power: they would lash together 50-pound sacks of flour, straddle two chairs, and heft hundreds of pounds into the air.

Many men in the camp cleared 400 or 500 pounds before their strength failed them. French Louis and Olaf Henderson, the two giants, reached 750. Daylight set out to beat them, not by a single sack, not by two, but by three. And so he strained to hoist 900 pounds of flour, early in the morning, having already lost all his money, danced all night, and drunk himself silly. This is what happened:

At this point, Daylight refuses to rest with victory and so taunts the room to best him in a round of wrestling. You can bet safely how this too turned out. Going up again against the biggest of the men, Daylight and his opponent:

"The winner pays!" yells Daylight, and he buys a round of drinks for the house. From the very beginning, it's hard not to be drawn into the gravity of Burning Daylight's vigor. We, as readers, want him to win.

All that single-minded vigor breeds enormous success. Yet it comes with costs. Early on, we learn that Daylight is afraid of women. He fears "the apron strings" of domesticated life, that he will be unmanned and stripped of his sovereign freedoms by giving his heart over to a lover. Atop this misogyny rests a celebration of white supremacy, as Daylight outruns his Alaska Native companion, Kama, and two others who Daylight hires when Kama's strength fails. The indigenous people in London's novel are portrayed as noble, but not as real characters and they are distinctly out-manned by the white guy in London's telling. Mix in a disgusting dose of anti-Semitism too, as Daylight bests the Jewish "Guggenhammers" in a massive gold mining scheme and treats them with undisguised, racialized disdain.

Were readers meant to identify with Daylight's white, protestant masculinity, or were these meant to be warning signs? Or, could both interpretations be true at once?

It was amidst Daylight's great Alaskan victory over the Guggenhammers that it first dawned on me how London had drawn up Harnish/"Burning Daylight" in the same way that Emerson treated Napoleon: both were perfect men of the world, men who the reader could not help but root for, and who proved that the world's values pretty much sucked.

One day, having built a small fortune through land claims and by selling supplies and lumber to a flood of greedy prospectors, Daylight surveys the landscape.

Briefly, Daylight recognizes the terrible waste that his own actions have made possible.

But only briefly, for at the same moment, he devises a plan to make this random, haphazard environmental destruction even more efficient: "Organization was what was needed." And Daylight would do the organizing.

"By 1898," wrote London, "sixty thousand men were on the Klondike, and all their fortunes and affairs rocked back and forth and were affected by the battles Daylight fought." Seeing that the Guggenhammers and their English partners sought to create a large industrial mining system, Daylight strategically bought up claims to block their way. Finally at a place called "Ophir", Daylight's claims stymied his opponents, who sold their much larger claims instead to Daylight. They didn't think he could handle so large a territory. They were wrong. Daylight would do the organzing.

Daylight had a vision. He hired engineers, built a reservoir with miles and miles of piping, set up an electric power plant, and used his own network of sawmills to supply his vast building needs. The mining works he created flooded the market with gold, ruining many of Daylight's own one-time compatriots among the small-time prospectors. But by that time, Daylight had already sold-off all his small claims, his sawmills, and supply shops. Soon, he'd sell the industrial mine to the Guggenhammers for a million or more dollars.

What a bleak transformation.

The beauty of Alaska transformed, denuded, even more completely than before, while the men who we had come to see as Daylight's friends and companions are now reduced to faceless workers, doing meaningless work for wages under the harsh electric lights. Daylight's victory here results in devastation for the land and for its inhabitants. And having won, Daylight packs up and heads to San Francisco in search of new opportunities to prove his mettle.

Daylight enters the world of finance. He makes massive deals and out-thinks his opponents. He is fleeced by a few of the leading money men (seemingly stand-ins for John D. Rockefeller, J. Pierpont Morgan, Jay Cooke, and of course Solomon R. Guggenheim), but he gets his revenge on them. We as readers root for his victories.

Then Daylight falls in love and his beloved will not have him, so long as he is driven only by the desire to destroy his opponents. She convinces him to use his money productively. Daylight responds by buying up much of mostly-undeveloped Oakland, California. He consolidates the water company, an electric streetcar company, and a ferry. He ploughs his profits back into the city, building up infrastructure to absorb the population overflowing from across the Bay in San Francisco.

When an economic panic strikes, Daylight somehow manages to hold his major enterprises together. He fends off creditors and employees alike, holding everyone out of bankruptcy. Together they muddle through and come out poised to thrive. All except for Daylight, who has transformed himself from the greatest of gamblers to a master builder.

Still, his ambitions consume him.

The novel concludes when Daylight intentionally drives himself out of business. He marries his beloved, Dede, and moves to a farm in Sonoma. There, one day, he stumbles upon a small vein of gold and imagines that he might start it all again. He could get back into the game.

That's when Dede's voice reaches him, rousing him from his reverie and he resolves to plant a forest of eucalyptus over that gold. No one will know it is there.

What, then, are we to make of all of Daylight's adventures? They were exciting. They were bold. They evidenced the extraordinary capacities of the most extraordinary of men.

And they were meaningless, a "chasing after the wind" as the writer of Ecclesiastes might have put it.

What does this mean for the reader? The most charitable interpretation is that London has provided people a fantasy to protect them. They may delight in Daylight's quest for dominance, saving themselves from that ultimately terrible fate. They can just stay in their farms and read the Herald.

But is that reasonable? Surely, a generation of readers instead read London and decided to get into the streetcar business.

This is the fundamental problem of a well-constructed critical expose. The act of exposure can attract at the same time that it condemns. (See also, every book or film about Wall Street. I'm thinking especially of Michael Lewis' Liar's Poker, which asserted the emptiness of investment banking and still drove masses of its readers to seek out jobs on the street.)

When we swim in the sea, who is prepared to condemn the water?

The dilemma of critique is that it requires using the values of a society to win and keep the attention of readers. But having used those values, what effect can the exposure of their limits really have?

I'll close with one final passage from Emerson:

The story of Napoleon the conqueror excites us. What sort of story inspires a world "with all doors open?"

Thanks for reading, friends.

Dan