Friendship, MOONBOUND, and next Monday in NYC

My dear readers!

It is summer here in New York City. That means I must attempt to solve one of the enduring tensions of scholarship in the molten city: how to wear as little as possible when roaming the streets, and yet somehow fend off goosebumps in libraries and archives. (I was frozen out of the NYPL reading room the other day. I will do better.)

The summer season also brings the beginning of BEACH READING. Now, I personally am more of an admirer of the idea of a beach; I leave the actually sandy and wet places to others who will enjoy them more. But surely one can beach-read anywhere when the sun is this hot. No?

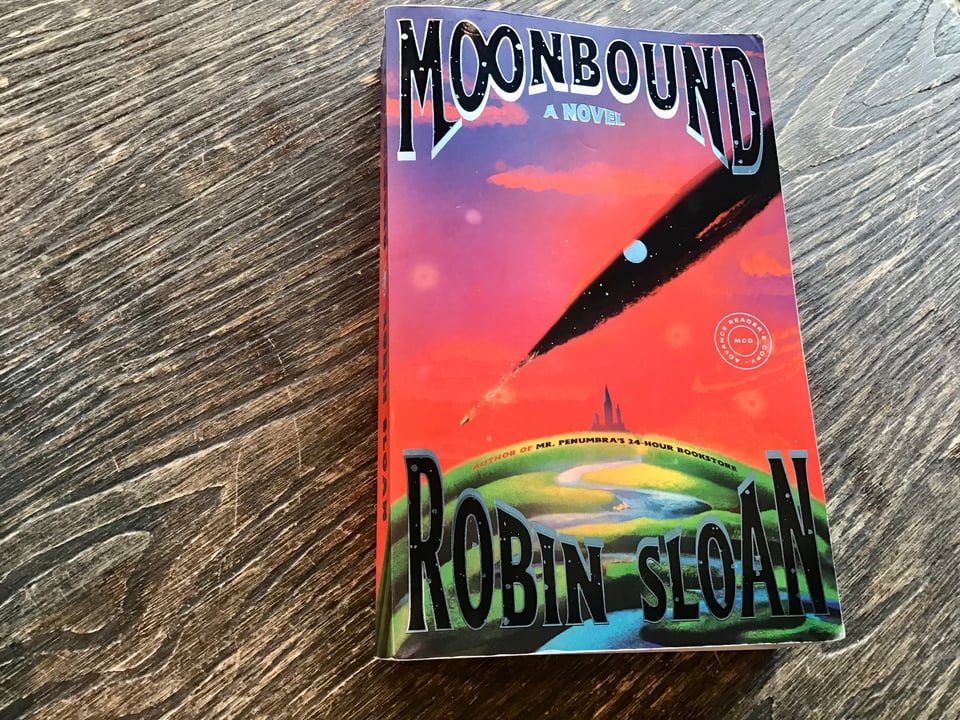

And you, my newsletter people, should luxuriate in MOONBOUND, which is coming out on Tuesday. (That gives you a few more precious hours to pre-order!)

If you're in NYC, come to Brooklyn's Greenlight Bookstore on Monday, June 17 at 7:30pm to geek out with the author, Robin Sloan, and with me.

Let me tell you a story. It is about friendship.

Early in this recently-concluded semester, I noticed two students passing notes back and forth in class. They were two among under a dozen in the room--a truly tiny class. There was no place to hide.

So, what were they doing passing notes with no apparent shame?

These two young people never wavered, even as my gaze lingered, telepathically warning them: "I see you!".

They handed a phone back and forth, gesturing and making ancillary notes on paper. Then one raised a hand, and responded with surprising clarity to a question posed by another classmate. The note-passers were, it turns out, listening.

I grew more intrigued: What were they doing?

I had my suspicions.

Looking at these two early-twenty-somethings taking American intellectual and cultural history, I saw myself and my best friend. We had been at Michigan State in a course called American intellectual history. We passed notes constantly. We giggled; we smirked.

What were our notes about?

Approximately 100% of them were about history. More specifically, they treated American intellectual history, as told by our beloved professor: a story-teller who lumbered in every day, wrote three words on the board and proceeded to summon a lost world for us. His name was David Bailey. We were entirely in his historical thrall.

I remember one day when my friend and I skipped class. We had what we thought was a good excuse: we'd been up all night seeding the campus with a total of 5,000 copies of our literary magazine (called OATS, but not about the "champion of cover crops"). This was our first time printing at so grand a scale, in newsprint, and it turned out that simply moving that much paper took a long time. We were exhausted. We decided to sleep. Bailey would understand.

But he didn't. "Where were you," he asked. That day he had prepared something special to talk about, for us. I don't remember now what it was. But he was disappointed. I get it now: we were an eager audience, and he needed us just as much as we needed him.

I felt the same way about those two students last semester, the note-passers in my class.

At the end of the semester, we read Gabrielle Zevin's Tomorrow, and Tomorrow, and Tomorrow. It is a devastatingly beautiful book about friendship and about a very particular kind of love: the love that comes from building something with other people. (My teenager was in the car with me on a long trip listening to the novel. He kept saying "why are they like this? why can't they work things out?" I sat there, blinking back tears, and answered: "Can't you see... They just love each other so much...")

It turned out that my note-passers were not just sharing historical jokes. They were planning out their weekly radio show: a romp through the past set to contemporary tunes. It seems that they had discovered the love of working alongside a friend too.

For those who have not guessed this already, the friend I was passing notes to at the turn of the millennium was Robin Sloan.

Remember him? He is the author of that book MOONBOUND that you're pre-ordering this very moment. (Quite a few of you are reading this because of his newsletter, and so to you I say: thanks for joining us! For the rest of you, I apologize for the relative dearth of content shrouded-in-cloaks-of-boringness in this edition. It is Robin's fault.)

And remember that people near NYC can see Robin and I talk about stories that cross dimensions and genres and centuries and species. That's next Monday, 7:30pm on June 17 at Greenlight Bookstore.

Here's another story about friendship.

When we were in college, Robin and I would eat lunch once a week at the Snyder-Phillips dormitory. They offered free paper copies of the daily New York Times at the door and we would grab one to share. As we munched on french fries, we read. Every few minutes, one of us would say "oh hey, listen to this." Eventually we'd pass one another an article: "you've got to read this one next." Every great blog is an attempt to capture (and perhaps scale up) that perfect way of reading together.

The other day I was reading an article by another friend, the economist Manal Shehabi's piece on "Just Energy Transitions" in the Middle East. It's a fascinating piece, one that explains how possible paths to energy transition will create more diverse economies, if existing oligopolies don't prevent transition, and it shows how the paths to greener economies will require both water and energy, in deeply dry, hopefully decarbonizing places. Perplexing problems litter all paths forward, in other words, though Manal still manages to offer some concrete recommendations. As I read the piece, I sent Manal a stream of my responses and exclamations: like how clarifying it is to talk about "hydrocarbon-dependent welfare states" or how astounding it is to think that Oman desalinates 86% of its water. 86%!! How are those desalination plants not considered a wonder of the world?

Robin has always been alert to the miracle of human creativity. He will read this and I am sure he'll agree with me: definitely a wonder of the world.

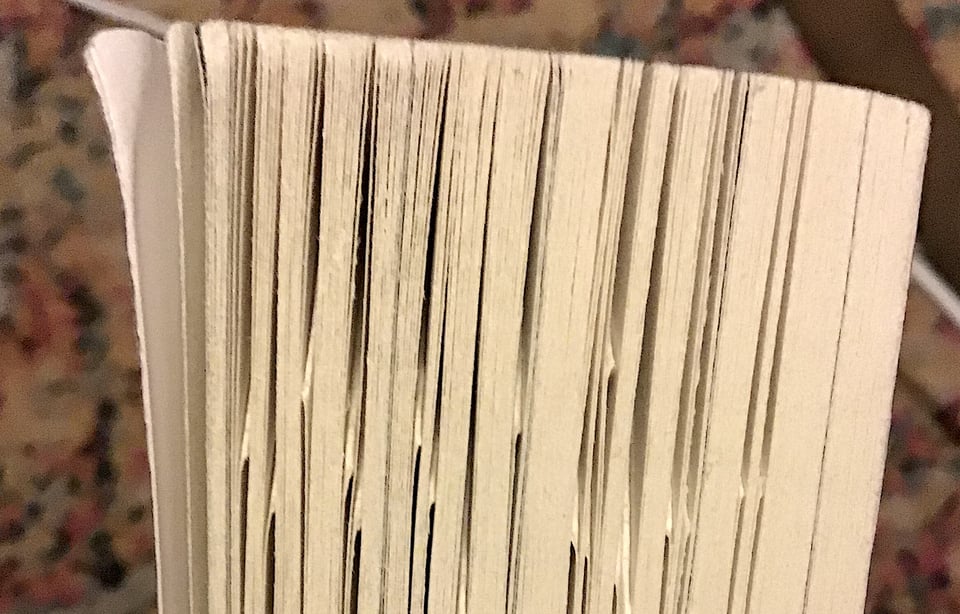

Reading an advance copy of MOONBOUND, I dogged the ears of so many pages. These were the spots I wanted to share with someone, as I would have with Robin twenty years ago. Imagine...

Robin, check this out, there's an incredibly pedantic beaver:

“Swamp! It is no swamp. A swamp is a low-lying wetland fed by an external inflow, generally inundated, often dominated by trees. This is a bog! Its water source is primarily rainwater, which results in a highly acidic and mineral-poor environment.”

Beavers are truly astounding creatures and MOONBOUND gives them their due. I was at the American Museum of Natural History recently and noticed a tree showing relationships among species. I had never realized that mice are close cousins to beavers. It makes me feel bad for mice: it must really suck to show up to the evolutionary family reunion and have to be constantly compared to your cladistic cousin the greatest mammalian terraformer!

Or, Robin, check this out, one character asks

"Where are you bound?"

and the other, a robot (of sorts) gives the perfect answer:

"I am not bound. I am walking. Are you not walking."

Reader, you better believe that I am walking (as much as possible) and I am definitely not bound when I'm doing it.

Or, Robin, check this out, in this one city in MOONBOUND,

"no one would ever go without food and shelter; these were always in surplus, freely given. The bathhouses were open to everyone."

Doesn't that just seem right? But/and: the city has also invented a new kind of economy, a new form of money, one premised on the capacity to endlessly recycle materials. As MOONBOUND explains further: "Beyond those essentials, any frivolities required a balance of matter."

Or, Robin, this is the last one for now, but these are a few perfect lines:

"So the representatives of the planet’s most successful civilization were a capacious fungus and a talking sword. More than a few philosophers of the Anth [the aforementioned 'most successful civilization'] would have found it appropriate, even funny. That was something."

Something, indeed!

Part of the pleasure of being friends with Robin is keeping up with his curiosity and his hunger for beautiful new ideas, for creative possibility. The world gives us so many reasons to be jaded and suspicious---so many very good reasons!---and yet Robin insists that good things are still possible; in fact, good things abound. In 2018, for instance, while I remained (and remain!) wary of machine learning, Robin built the most delightful not-too-large language model and used it to explore "sentence space": the imaginary planes of human creativity that link two sentences in an English-language corpus. The result was a strange and compelling kind of poetry.

MOONBOUND is a novel populated by beavers who believe in rigorous, reasoned argument (and organic, analog computing), by yeasty microbes devoted to historical narrative (no offense taken, Sloan), and by a profound devotion to our shared potential to make magnificent, beautiful, and salubrious futures.

Read MOONBOUND for the story, for the plot, and for the delightful characters (and all their friendships)! But it is also a great novel of ideas, a novel tempting us to imagine what might be. Consider this description of language in the human future, a language that has no "I":

The language of the Anth at their apex was far too circumspect to plant such a flag. In that language, there was no first person: their narratives swarmed and glistened, many-angled, shimmering with contradiction. That’s how the world is, a lot of the time...

What, I wonder, would it be like to live without the "I"? What a blooming, buzzing confusion befitting our world.

That "blooming, buzzing confusion" line is from William James's Principles of Psychology, but I want to close this newsletter with another apt line from James: one of his most famous from the essay, "The Will to Believe."

Objective evidence and certitude are doubtless very fine ideals to play with, but where on this moonlit and dream-visited planet are they found?

MOONBOUND is the perfect book for a moonlit and dream-visited planet. And it shares with James this too:

I am, therefore, myself a complete empiricist so far as my theory of human knowledge goes. I live, to be sure, by the practical faith that we must go on experiencing and thinking over our experience, for only thus can our opinions grow more true; but to hold any one of them--I absolutely do not care which--as if it never could be reinterpretable or corrigible, I believe to be a tremendously mistaken attitude...

Go read MOONBOUND, and prepare to reinterpret your experience, and gird your loins for the dragons too!

your friend in "beach" reading,

Dan

(and here I am, just a bit too cold, at the NYPL...)