Conspiracy or Complexity and the 4th of July

Dear Reader,

Hello! It has been a while. You're receiving this because at some point you signed up for this newsletter. If you want, you can unsubscribe at any time. You can also, at any time, buy a copy of DEMOCRACY'S DATA from your local bookseller and give it to a friend. Can you think of a better gift to bring along to your 4th of July celebration? (Sure. Of course you can. But this "endearingly nerdy" book would be so surprising!)

You're reading "Shrouded and Cloaked, a Boring Newsletter." My website is www.shroudedincloaksofboringness.com. My bio says I am interested in "bureaucracies, quantification, and other modern things shrouded in cloaks of boringness." I am, if nothing else, consistent in my branding.

Last December, I showed up at ABC's studios in midtown New York for an interview with Galen Druke of FiveThirtyEight and Galen pressed me on the question of boringness. Click here and go to 1 minute, 30 seconds (1:30) in the video to see for yourself.

Check out my face as Galen frames the question.

I'm smirking with my eyes. I know what is coming, but people don't usually ask it outright.

Then at 2:15 we get there: Galen asks me exactly how much of a conspiracy theorist I am.

Here's that moment.

I've been thinking about that question a lot, ever since. It is such a good question.

You can watch and see how I answered back then. Basically, I said that I believe the people who design big, complex social or technological systems often engineer in some extra boringness. To be boring might be a feature, not a bug. Amping up the arcana and juggling extra jargon can make it easier for those in power to avoid scrutiny or interference. So: I am a bit of a conspiracy theorist.

Looking around since then, I've discovered that I am not alone.

Consider this, from the voiceover of Ryan Gosling's character (the cool banker guy) in the movie The Big Short:

Mortgage-backed securities, subprime loans, tranches. It's pretty confusing, right? Does it make you feel bored, or stupid? Well, it's supposed to. Wall Street loves to use confusing terms to make you think that only they do what they do. Or even better, for you to just leave them the f*#! alone.

Or, consider this excerpt from a conversation about ad tech, between reporters Charlie Warzel and Shoshana Wodinsky:

Warzel: "I think it’s this way on most beats but I find it especially true in covering privacy and data issues. A lot of this stuff is like, purposefully dense and dull. And the most interesting stuff is always the most impenetrable s*#!. You basically need almost like an advanced degree to understand how your data moves across the internet...."

Warzel: "Do you think that a lot of the adtech stuff is actually complex because it needs to be? Or do you feel like it's complex because it's the wild west and people are making it up as they go?"

Wodinsky: "I feel like some of the technique is hiding the incriminating stuff in the boring stuff. I think the field is incomprehensible on purpose for two reasons. The first is that, when you talk to people who work in adtech candidly, almost all of them know that the field is rampant with fraud and abuse and really just grifters. I don’t think it would be as complex if it weren’t trying to hide a lot of that fraud. Second, many of these ad companies and data exchanges know investors, shareholders, and hedge funds (which use a lot of this data as corporate intelligence) don’t understand this stuff either. All our personal data is ricocheting back and forth in a giant Russian nesting doll of black boxes and algorithms and nobody is cracking it open because who has the time?"

Or, from Evan Osnos in "Trust Issues: A Disgruntled Wealth Manager Exposes Her Clients' Tax Secrets," New Yorker 23 January 2023:

But perhaps nothing has contributed more to the latest revival of dynastic fortunes than a spate of innovation around trusts, known by such recondite acronyms as SLATs, CRUTs, and BDITs. (The opacity is no accident. The late U.S. senator Carl Levin, a critic of finance abuses, accused the industry of deflecting attention with MEGOS---'My Eyes Glaze Over' schemes.)

And yet!

I also believe that operating expansive, elaborate systems necessarily results in the sort of technical minutiae that is, for lack of a better word, boring: both for the uninitiated and even for the skilled practitioner.

Here's an example, for this 4th of July, from the debates over expanding the House of Representatives.

The political theorist (and recent candidate for Massachusetts governor) Danielle Allen has been beating the drum in a series of Washington Post columns in favor of adding seats to the House. (Readers may recall that I also think this is an idea that is long, long, long overdue.) As Allen puts it, "growing the House of Representatives is the key to unlocking our present paralysis and leaning into some serious democracy renovation."

Looking back at the moment of the nation's founding, Allen argues that the framers intended for Congress to keep pace with the country. Instead: we've let the people's branch fall farther and farther behind.

The expectation was that good, responsive representation required allowing representatives to meaningfully know their constituents, constituents to know and reach their representatives, and Congress to get its business done.

Today, House members represent roughly 762,000 people each. That number is on track to reach 1 million by mid-century.

How this happened is something I investigated in depth in House Arrest, a Data & Society report in 2021. You'll also find more in Democracy's Data.

A stagnant House is a problem, according to Allen, because

- members of Congress are less likely to know or be able to care for their constituents;

- they need more money (and so more fundraising) to run in larger districts;

- it offers a limited number of opportunities for new voices to enter the government;

- and that fixed number of representatives has a growing federal bureaucracy to oversee.

I agree with Allen on all those points. And what's more, I think this is a relatively painless way to shake up our political system and infuse it with more democracy. I'm coming to you here on this 4th of July and I'm saying more democracy is a good thing.

(This might also be a good moment to recommend Allen's book on the Declaration of Independence, which is one of the best: Danielle Allen, Our Declaration, published in 2014 by Liveright/Norton.)

So far, so good. But what does this have to do with the boring stuff?

I'm getting there.

In Allen's next Washington Post column, she got down to numbers. "Democracy," she wrote, "is about words and law, oratory and policy." It "is also about math."

The question is: how much bigger should the House be?

Allen considers a variety of possible principles or rules that might be used to settle on an appropriate size for the House of Representatives. I won't go into them all here. The one that Allen lands on, for the moment, is what she calls "the Deferred Maintenance Rule." Here's her description:

When the size of the House was capped in 1929, new seats could shift to growing areas only by taking them away from other areas. The number of seats lost by particular states since 1929 through this method is 149. If we restored those seats and added one more to keep the total an odd number, then reallocated to achieve even districts, we would have a new base of 585 seats. This method is clean and yields districts slightly smaller than the current population of Wyoming. However, we would still need to figure out a principle of growth under this method. Would we take district sizes after such a reform as the standard ratio, and simply let the House grow in relation to it? This, too, would result in relatively fast growth

We would expect Allen to land here. She chaired an American Academy of Arts and Sciences commission on the future of democracy, which put out a bipartisan report, by Lee Drutman, Jonathan D. Cohen, Yuval Levin, and Norman J. Ornstein. That report included the calculations that got to 149 seats "lost" by states and put that forward as a good first step.

I'm fine with adding 150 seats.

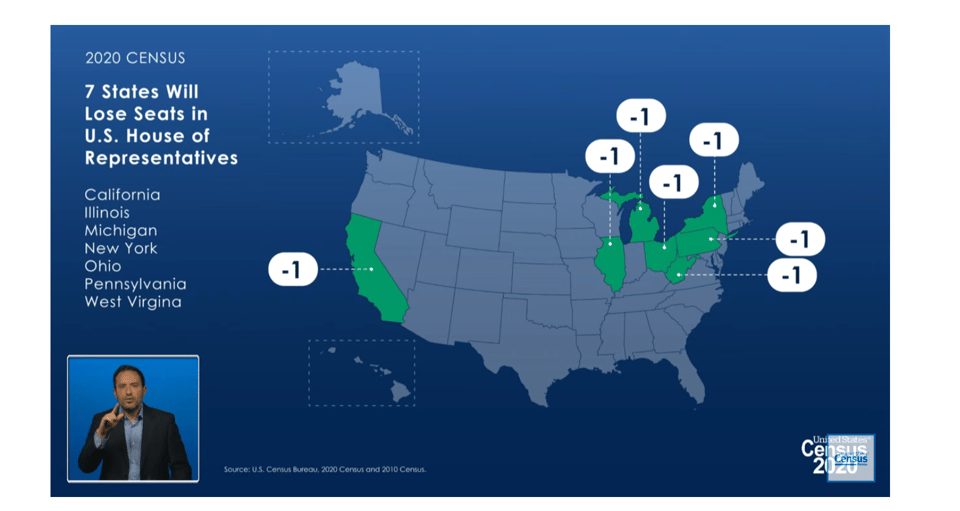

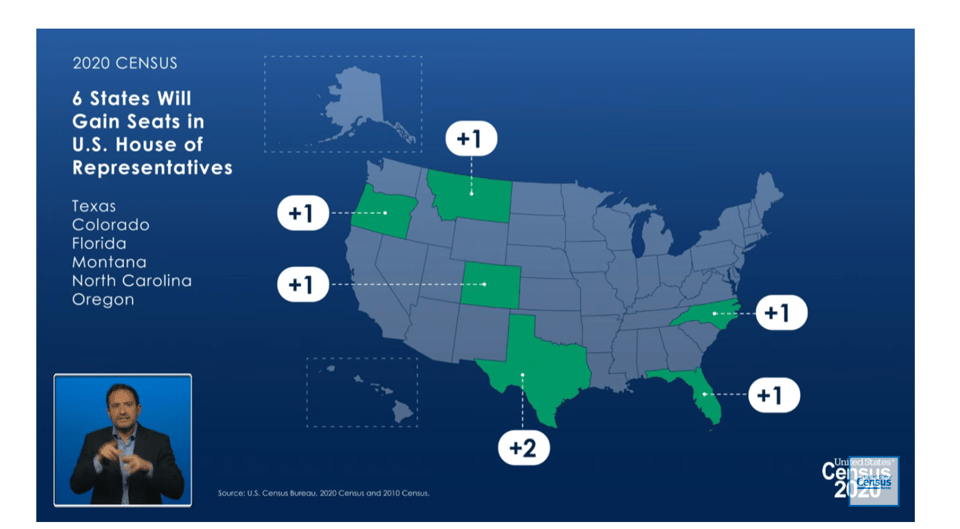

The thing is that the number 149 is mostly arbitrary. It comes from adding up the number of seats that were taken away from any state in the process of apportioning representatives every ten years. So, for instance, after the 2020 census, the apportionment process resulted in seven states losing a single seat each: California, Illinois, Michigan, New York, Ohio, Pennsylvania, West Virginia.

Six states simultaneously gained a seat: Colorado, Florida, Montana, North Carolina, Oregon, Texas (gains 2).

The reason Texas got two was because it was growing so much faster than other states. It got one seat and then it's "turn" came around again to get a second seat before any other state in line.

Now, if the Academy logic held true, then adding seven seats would prevent any losses of seats. Let's see if that would have worked. To do so, I'll fire up my spreadsheet where I have the apportionment algorithm programmed in with some macros. The result, (as I previously calculated here) is that a House of 442 seats would result in this allocation:

House Size: 442 seats Seats gained: 11 / Seats lost: 4

Gainers: Arizona, Colorado, Florida (gains 2), Montana, North Carolina, Oregon, Texas (gains 3), Virginia

Losers: Illinois, Michigan, Pennsylvania, West Virginia

Whoops! There are still four states losing seats. That's because they grew so much more slowly than Texas and Florida that those two states lapped them again, and some other states jumped into the gainers bracket before the slow-growers worked their way out of the losers bracket.

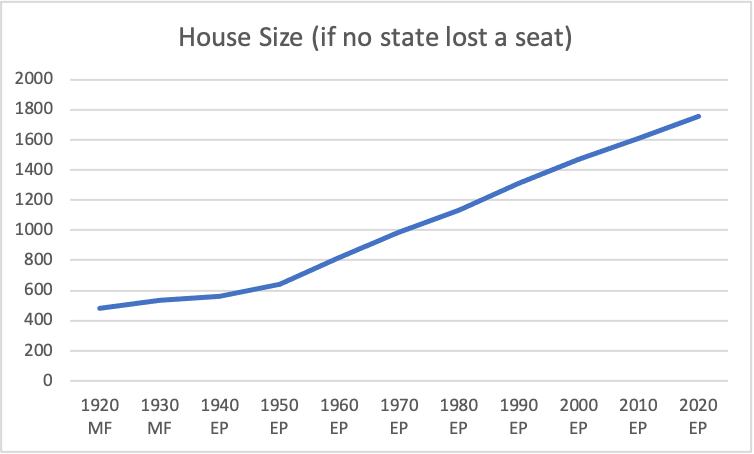

It turns out that you would have had to add 19 seats after the 2020 census to get to a place where there were no seats taken away. And, by my calculations, if we really wanted to practice "deferred maintenance," returning the House to the size it would have been at if none of the seats were ever taken away from a state since 1920...well, that is a much bigger number (so big that I'm not sure I've ever published it): 1,752 seats. That means we'd be adding 1,317 seats---roughly triple the current membership.

Here's what my model says the size of the House would have looked like every ten years with no losses to any states:

(Note: someone should check my math on this!)

Is that the right solution? Probably not. I don't think so myself. I think 150 new seats sounds more doable. I'm also in favor of just getting rid of our automated apportionment system entirely, which I think would result in a natural growth of the House every ten years. I made that case in WIRED last year.

My point is this: Allen and I agree on the principle. The House should grow.

Now, say we also agreed on a principle for that growth: the House should grow such that it "defers maintenance," restoring seats that had been lost.

Ah, here we've run into a problem. Turning that principle into a number of seats to add mires us in a sea of spreadsheets, Excel macros, and a lot of historical census data. We've jumped the shark from simple and interesting to complicated and...well, maybe...boring?

What do you think? Be honest, was this getting boring?

No one built the apportionment system to make it boring. We just need mathematical principles to ensure that representation is proportional. The problem is that it is slow-going to get through all the math and the data. This, it seems to me, is boringness resulting from complexity, not conspiracy.

What do you think?

Toward the end of that FiveThirtyEight interview, we got into some of these questions about apportionment. Jump forward here to about 47 minutes in. Then, at 49:48, Galen asked me what the most American number is. It took me a second, but then I realized the "correct" answer.

538, naturally. (Which is the number of electoral college votes, arrived at by adding up 435 House seats, 100 Senate seats, and 3 electors for Washington, D.C. So if the House were made larger, the number of electors would increase by the same amount.)

538, that's an American number now and one that seems natural, timeless, and inevitable. Here's hoping that Danielle Allen wins enough people over and we make a new (higher) American number. 688, anyone?

I'll leave you all with a few recommendations.

If you're looking for a different way to understand the American founding, check out Hannah Farber's Underwriters of the United States. It turns out your revolt against a globe-spanning empire may require some assistance from a globe-spanning network of insurers. (It just won the prize for the best book in business history, too.)

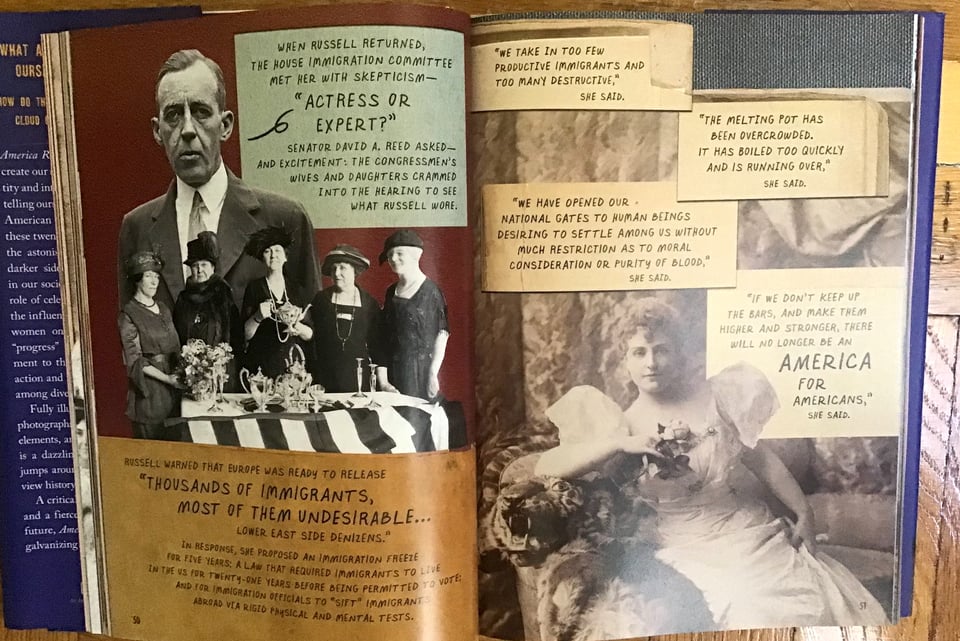

I also recently received Ariel Aberg-Riger's new book, America Redux: Visual Stories from our Dynamic History. It is an inspiring, provocative, infuriating, and immediate interpretation of cascading historical moments, a presentation of history tuned to our times---indeed, it opens with a story about the Daughters of the Confederacy and about conservative backlash against liberation that feels ripped from the headlines. And it is all beautifully built, history as art.

About her method, Aberg-Riger writes:

It wasn't until I was well into my thirties that I fell into a relationship with history, and it happened through images. I began searching historical archives for photographs and objects and artifacts I could collage into my art, and they called me in. I found myself wanting to know more about who the people in the portraits were. I wanted to know their stories.

Over at the blog, I wrote about "#NYCPride, data systems edition."

Last Sunday was the NYC pride march, which I celebrated (as one does) by digging into my pile of reading on queer data.

First, I opened up the Biden administration’s Federal Evidence Agenda on LGBTQI+ Equity....It turned out to be surprisingly good....

In my #NYCPride celebrating, I also picked up an article I had been meaning to read for a while, by one of the most important and original voices among historians of computers, Mar Hicks. In a 2019 article, “Hacking the Cis-tem,” Hicks explained how their diligent FOIAing of British government pension-office documents had revealed a very early example of what we now call computerized algorithmic bias....

Here is an inspiring point. No one wants to spend time fighting to get their name or gender corrected in a pension ledger—that so many people did so is a testament to their resolve, and an expression of queer activism that deserves our celebration.

Want a refresher on why the census matters? Check out this interview with the folks at the Leadership Conference on Civil and Human Rights.

Long before I attached myself to the boring label, Susan Leigh Star, Charlotte Linde, Geof Bowker and others joined together in a "Society of People Interested in Boring Things." (See the note to Star's classic "Ethnography of Infrastructure" paper.)

So, I was thrilled to join Geof Bowker in this conversation about CLASSIFICATION, hosted by Sareeta Amrute and organized by Mona Sloane as part of the Co-Opting AI series.

That's all for now folks. Coming up this summer, I will wax enthusiastic about spreadsheets, dig into municipal infrastructure and budgets, write about housing, maybe some AI and dataset politics, and much, much more.

Until then, take care all, Dan