Unfolding lost circus posters - #2

The Bennington Museum exhibits once-lost print fragments of shows from the turn of the 20th century. The risky preservation effort picked apart dozens of layers pasted atop one another to reveal scenes of wild animals, acrobats, and Wild West shows.

The Bennington Museum exhibits once-lost print fragments of shows that passed through at the turn of the 20th century

In summer 1972 Nicholas Whitman was a young photographer just out of high school, traveling around the area looking for things to photograph. In North Petersburg on Route 22 he noticed an uncanny image of what looked like a tiger seeming to peek out from the wall of recessed alcove at an old yellow barn on the corner.

That had been an important intersection, and from the 1890s to 1910s every circus and Wild West show that passed through the area pasted up lithographs advertising their shows, a kind of early mass media for the first mass entertainments. The cheap posters were intricately designed, but never meant to last and few survive.

Thirty years after that first photo Whitman revisited the site and found it had become an antique store. He asked about that wall, and they pointed him to the attic, where he found two panels, each about three feet by five feet in size and about ¾ of an inch thick. He took them home. He wasn’t quite sure what to do with them, and even professionals who worked on prints and circuses seemed interested in what might have been hiding in its folds.

To conserve the fragile images, Whitman consulted with Leslie Paisley, a recently retired paper conservator. Over email they had a lengthy and honest discussion about the ethics of attempting such a delicate restoration. “We knew it was risky to disassemble it,” Whitman said. “But if it stayed together, it was just a sandwich of paste and paper. It wasn’t good, and it wasn’t going to last. The gamble was whether to take a shot and risk destroying it or leave it as good as destroyed because you couldn’t see it.”

The process they devised involved building a shallow tub to soak the panels, periodically flushing out the water. After about a week, the water began to run clear, and the paste loosened. The pieces were carefully unrolled and placed on acetate, using spatulas to assist. “There was a lot of triage,” Whitman said. “We could never know what we had. Sometimes, things wouldn’t come apart. Sometimes, they were just hopelessly damaged.”

The exhibit in Bennington includes photographs documenting the conservation process. Whitman said he did no color enhancement or editing, aiming only to restore how they originally looked. The 40 images are tantalizing snapshots of what was passing through in those years — from animal acts with hippos and monkeys on ponies to acrobatic feats and traveling productions of Uncle Tom’s Cabin. Mixed in were advertisements for products like horse medicine and political campaigns for local offices. Advance teams would paste these posters around the area, usually near railroad tracks, along with date sheets advertising the shows.

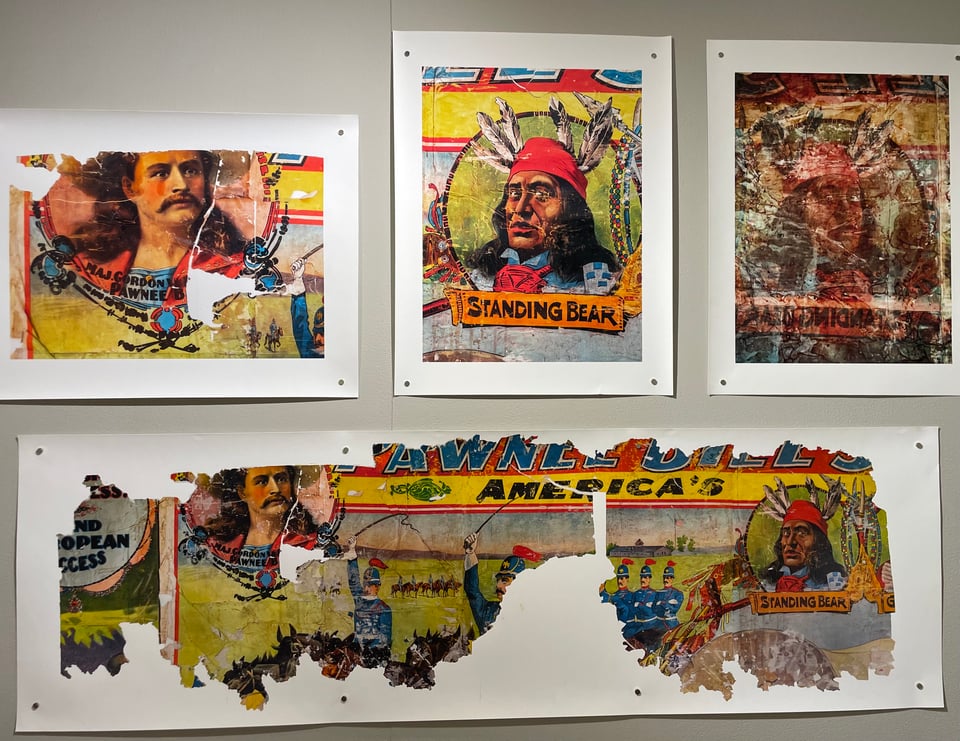

One of the most complete and striking fragments is a part of a notice for Pawnee Bill’s Western show, which was one of the most popular of the era and a friendly rival of Buffalo Bill who also toured with similar shows. This one featured Standing Bear, a leader of Ponca nation in the 1870s who was the plaintiff in a federal lawsuit that established Native Americans as people with legal standing in the eyes of the law. By the time the traveling show rolled through upstate New York he was making money by appearing in these kinds of shows.

Remarkably, this is the only fragment for which a complete finished copy exists. A sun-faded version is on display at the Pawnee Bill Museum in Pawnee, Oklahoma, and Whitman sent images of his copy to them. “They were excited because this one has the correct color,” Whitman said.

On another level, the fragments also exist as a kind of collage art. The layers of bright colors, jagged lines, and abstract kaleidoscopic images create an artistic experience in themselves. As the pieces emerged, Whitman often photographed them. He sometimes climbed a ladder to capture the transitory beauty of these fragments, recording the delicate process of unrolling and revealing images that were “so fugitive and transitory.”

Whitman hopes that the originals will find a home in some kind of collection, and they captured their process and the images in a book.