This is the artist, and this is the Art! - #5

David Lynch and the power of personality, with an aside about Édouard Manet

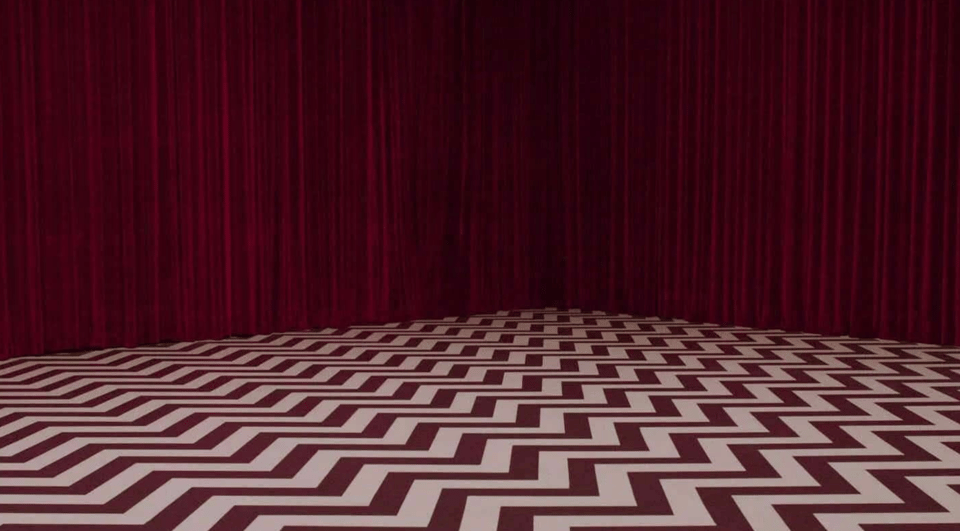

An early lesson for me in the power of art was watching my hockey teammates argue in the locker room before practice about an episode of Twin Peaks from the night before. Now that even the idea of mass media seems to have died, it is hard to believe the kind of cultural penetration this very weird series could achieve. It remains a great mystery it even appeared — this murder mystery, soap opera, afterschool special, and European arthouse film — let alone earned such sincere analysis and debate. Like the best art, it taught you how to look at it.

Of course, I can’t vouch for how long those lessons stayed, as everyone seemed to grow more bored and tired as the mystery of Laura Palmer’s death was resolved. It was gamble for attention that David Lynch turned into something amazing: no other artist lured you into the search for a literal meaning, with the brazen refusal to offer one. It became the point itself, and if I may get poetic for a moment, it led you to realize these assumptions of cause-and-effect and predictability are an illusion. Without them you find yourself in a field of vibes, connected in awe and wonder to the beauty of the world, or alone and stranded in the fear and terror of realizing how small and confused you really are.

Like so many other film lovers I mourn the news that Lynch passed away last month. A death marks the closing of a chapter and is an opportunity to revisit a lot of work — as Images Cinema in Williamstown will be doing over the next few weeks. But I also notice that old narrative trap. There has been an outpouring of affection for the artist, for his Zen weather reports and famous quirks — his love of Bob’s Big Boy and strong black coffee and milkshakes. There is something very appealing about someone so peculiar yet functional (“Jimmy Stewart from Mars” as Mel Brooks put it) who could consistently and confidently produce art that uncompromising. That people loved it makes it magical.

I feel I’ve seen more of the vibe-based persona affection for Lynch than engagement with his work. And there is a lot to think about there. For example, I recently came across an interesting line of though from a piece by Jonathan Rosenbaum in Film Comment in 1990, describing J. Hoberman’s idea of the “conservative avant garde” and how Lynch could easily be included. These were filmmakers like Andrei Tarkovsky, Stan Brakhage, and Hans-Jürgen Syberberg who Hoberman said “see their art — and all of Art — as a quasi-religious calling… [they] tend toward the solipsistic, invoking their parents, mates, and offspring as talismanic elements in their films. All three are natural surrealists, seemingly innocent of official surrealism’s radical social program. All three privilege childhood innocence… and all three are militantly provincial.”

To make a bit of a leap, I’ve been thinking about how the personalities of artists can diminish them in a way. That was what I took away from great exhibit earlier this year at the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum in Boston about Édouard Manet. I don’t know if it still applies, but for a long time the art history survey course shorthand put Manet as one of the first modern painters to really grab you, who along with Gustav Courbet marked the shift into what painting could really be — the voyage away from say Guillaume Lethière to everything that has come since. He was a painter aware of the existence of cameras, that attempting to accurately capture an image was a waste of time, and that anything around you was more interesting than any imaginary Biblical or Classical scene. It placed art as something all around us.

The Gardner show closed last month and was a chance to visit 15 great Manet’s paintings. They are powerful to see in person — each an image you can recognize, if some have an element of ironic strangeness. But it is upon looking closer you see the craft made plain, the dashes and sweeps of paint and color that suggest depth and movement.

At this point, Impressionism is in constant danger of tripping over itself. A review in the New York Times of a big show about Monet and Dégas last year called them “preordained crowd pleasers,” and that loving them puts you in danger of being labelled “basic.” So the Gardner museum finds a new way of framing the paintings, telling a bizarre story about Manet’s puzzling family history. Specifically, it is about Suzanne Leenhoff, a Dutch pianist who was hired to be his music teacher and eventually became his long-time partner. She figures in many of his paintings, as does her son, Léon, whose parentage is uncertain and possibly very complicated (he may have been Édouard’s, or his father’s). The exhibit dwelt on this mystery at length, but for the life of me the story remained unsatisfying, and I could not quite bring myself to care about Manet family gossip.

After Lynch’s death I watched David Lynch: The Art Life (2016). As a documentary it is brave in focusing on the man’s history and ruminations, and stops just before his first feature, Eraserhead. We learn a lot about his work as a visual artist (think Francis Bacon) and his training (though he doesn’t really engage with why he crashed out of other art schools before thriving at the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts — which as the old joke goes is the best 19th century art school in the country). And he seems uncharitable about his disappointments, whether his adaptation of Dune or his four marriages. The final word on it seems to be not much more than that’s Just How Artists Have to Be.

But luckily, most of us don’t have to deal with the man. It is enough that he was a kind and skillful collaborator, that he was a clear advocate for the value of a serious, sustained meditation practice. And that in the end nothing matters as much as the process of making things and putting them in front of people.