Spring Break on the Riverwalk (the one in Tampa) - #7

About a visit to the Tampa Museum of Art, and trying not too hard to take a break from being a snob and just enjoy “a journey through time and imagination”

I had a few hours in Tampa while visiting family last month, and even though going there was to get into the sea and the sun for a while, I was happy to step out of it to visit the Tampa Museum of Art for a few hours. The museum is an anchor of the city’s Riverwalk, a downtown development not to be confused with similar concepts in San Antonio or Detroit or Providence. It’s a 2.6-mile promenade with playgrounds, dog parks, and terraced green spaces to host “downtown festivals” organized by the Chamber of Commerce to breath life into a district of office towers and high-end condos. It’s a very Florida contrast — a perfect tropical paradise outside, high culture within, and growth good and bad everywhere.

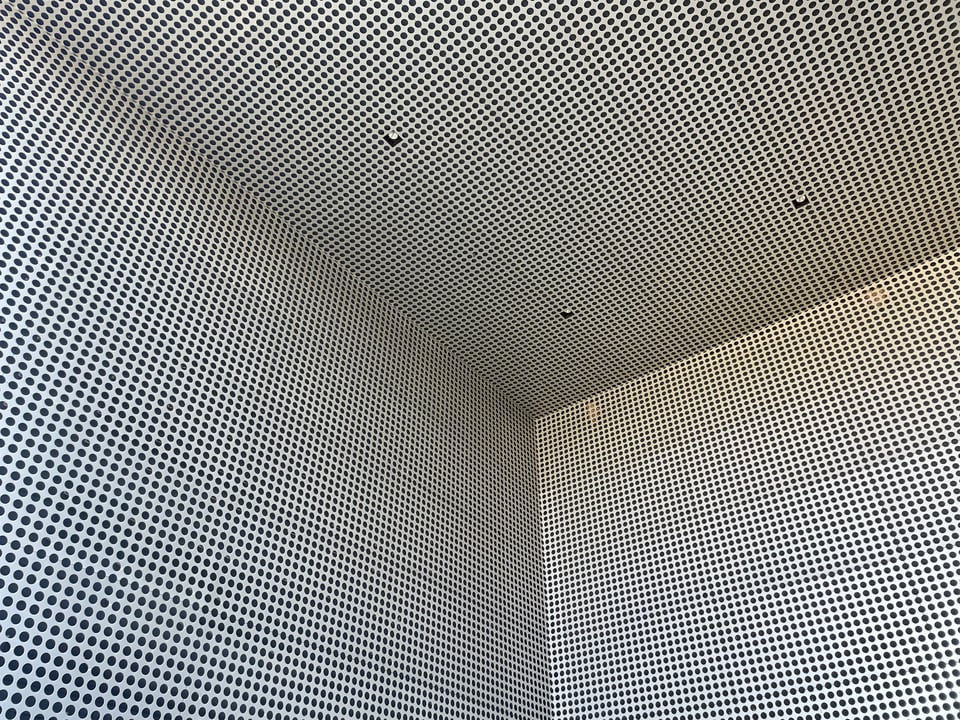

The building itself is a monument to civic optimism —a rectangular box wrapped in an aluminum grid creating an Op Art effect that's apparently irresistible to nesting starlings. San Francisco architect Stanley Saitowitz designed it to sit "almost like clouds or like water, constantly reconfiguring" above its glass lower level.

Reconfiguring extends to the way the museum uses language. Like many regional arts institutions, it employs a kind of high-falutin’ rhetoric that major metropolitan museums avoid. While the MoMA or the Met simply assume you know why they matter, smaller museums have to keep their hustle in plain view, with wall panels that exalt artists and works with a tropism toward superlatives. I couldn’t gather many specific examples — security scolded me for using a pen instead of a pencil, a rookie mistake on my part and eagle-eyed gotcha by them — but consider this line from their visitor’s guide:

Wander through our galleries and engage with a rich array of visual narratives and artistic expressions. This season promises a journey through time and imagination, deepening your connections to our global heritage and the innovative spirit of human creativity shown at TMA.

It's a far cry from grad school jargon about "interrogating" this and "intervening" in that. This is about luring you out of the sunshine for some Art Appreciation 101 — the eternal struggle for an institution claiming encyclopedic authority over a region's art and culture. It's about high culture and family fun, education about the past and prosperity for the here and now, a blank zone that practically whispers, "Wouldn't this be a nice place for a fancy party?"

The lower level offers shiny spaces while the upper galleries boast high ceilings and—when I visited—not many people. It feels open yet somehow exhibits and materials and tones smush together. A huge amount of space showcases their abundant Greek and Roman pottery collection, unfortunately displayed in possibly the most inert way imaginable: pedestals under glass with wall texts more didactic than inspiring.

Their permanent collection seemed mostly tucked away, but a few interesting temporary exhibits caught my eye, about Coptic art from late antiquity and contemporary Voudou-inspired flags from Haiti. Here are a few other things that caught my attention…

Art from Cuba

The biggest exhibit now is a collection of Cuban art (“Under the Spell of the Palm Tree: The Rice Collection of Cuban Art,” until July 6), and the one thing that followed me around the gallery was a collagraph by Belkis Ayón and Ángel Ramírez featuring a mysterious dark figure with piercing eyes handing something to a classic, stylized Byzantine St. George. It is a collagraph, a kind of print collage which Ayón specialized in, including recurring themes about Abakua, a secret men-only society with deep ritual lore and roots in faith practices brought from West Africa with the slave trade. Dando y dando shows the iconic figures exchanging greetings, with radically different presentations in a conversation between two vast globe-spanning systems. You always come away from a museum visit with at least one new obsession, and Ayón is mine, an artist who was making some striking work before her tragic premature death at 32 in 1999.

Suchitra Mattai

Indo-Caribbean artist Suchitra Mattai uses reclaimed fabrics and textiles to tell the story about her family’s life in Guyana as a place where many threads of cultures meet (“Suchitra Mattai: Bodies and Souls,” until April 20). The work is colorful, enormous, systems of braids and weaves, punctuated by symbols and gestures.

Purvis Young

The museum gives over a huge amount of wall space for an artist that defines local — albeit on the other side of Florida. Purvis Young was a self-taught Cuban-American artist in Miami, who created enormous outdoor works that in the 70s filled abandoned commercial spaces in his neighborhood. Using found materials and house paint, and fueled by an autodidactic obsessiveness and work ethic, Young explores an entire cosmology featuring knights and angels, social unrest and domesticity, hope and magic. But it feels a little lost in a sterile gallery space, and makes you feel everyone in the room is speaking too quietly. (“Purvis Young: Redux,” until June 29).

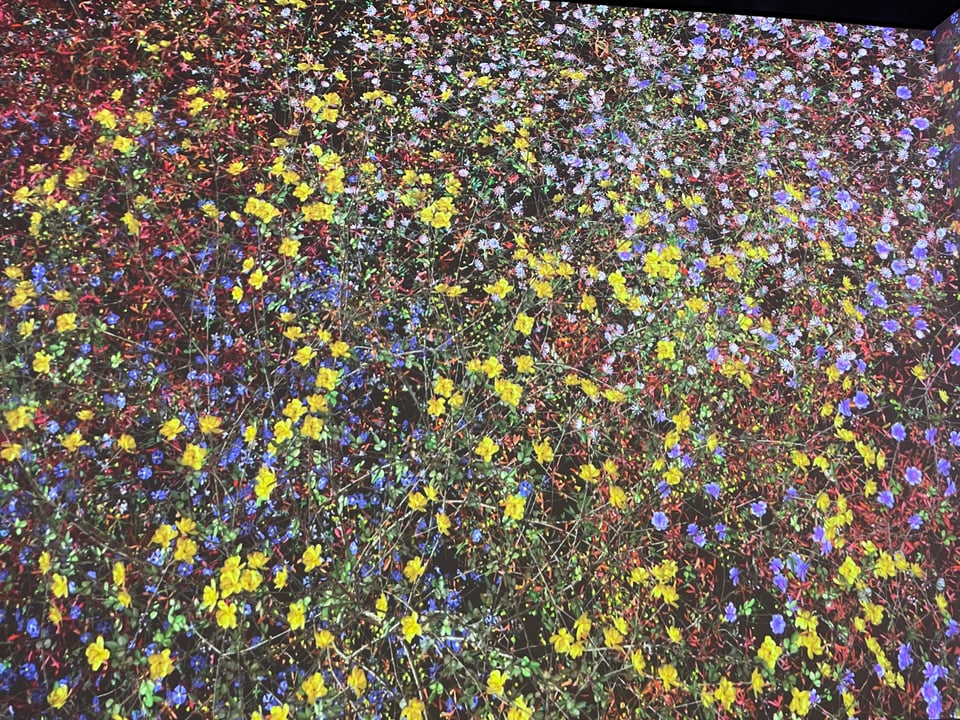

Jennifer Steinkamp

Every art museum needs something with a little ‘wow’ factor, and TMA gets it with a commissioned work from Jennifer Steinkamp (“Madame Curie,” through August 10). This room-sized installation takes a thin premise — that Marie Curie’s personal journals were full of notes about flowers and plants — and spins it into a full-field immersive experience. Images of flowers she mentions are multiplied and entwined, undulating like the sea, defiant of any deeper pattern.

The museum opened its current building in 2010, from a plan with roots deep in the optimism of "the Bilbao Effect." The first idea in the early 2000s was a massive Rafael Viñoly-designed arts district with a multi-block canopy. When costs spiraled, they scaled back and almost settled on the current design, which appeared the same time as the children’s museum next door. Now they're expanding again with a cantilevered structure that will jut over the Riverwalk and double their gallery space.

This prosperity makes me think about home, where we fantasize about billions of dollars magically appearing to merely restore the passenger rail service we gave up 70 years ago. Where we wonder which schools are going to close next, and if we’ll lose another congressman in the next census. Tampa has warmth, sunlight, and the kind of growth Americans once took for granted—yet the politics remain cramped and toxic, with so many atomized, angry DeSantis voters. It feels like cautionary tale, and the saga of the Tampa Bay Rays and their dream of a new stadium, raised to emergency status by hurricane damage last year, suggests nothing can be taken for granted.

This flavor of 21st-century urbanism is disorienting. Outside the museum, a steady stream of folks in athleisure wear ran and walked and pushed strollers by. Across the Hillsborough River, University of Tampa students sunbathed on beach blankets. Boats — those “beautiful boaters” of autocratic lore — puttered up and down. One that caught my eye was a party boat of sorts shaped like a giant barrel, a ridiculous round floating bar. This is a place that can afford a museum in growth mode — and perhaps more than most places, really needs one.