Showing up for 2025 - #4

On teaching, hearing from unfamiliar places, and embracing imperfection.

A few ways to think about getting started

Each new year starts at a run for me. I usually teach a short four-week class on journalism for Williams’ Winter Study term, so I spend the last few weeks of the old year worrying about it. What to do better in the new year, guest speakers to line up, how to talk about new developments in the field — which this year meant coming to terms with “legacy media” evaporating before our eyes. Almost every January arrives in a little cloud of dread that lifts once the class gets underway and the students emerge from names on a screen to become real people. By now, I’m always surprised how the experience is a way to reconnect with my profession and the world, and for a little while I remember why I chose this and what I like about it.

This year it unfolds against a particularly dire backdrop. There is plenty to say about this absurd and repulsive moment in history, and it is often hard to find way to think or write about anything else. Fine tuning our senses of self and boundaries in the face of this firehose of garbage will be important work for the next few years, as we come to realize we can’t rely on the long arc of justice.

Thinking about how things come into being brought me back to an exhibit I saw at MASS MoCA a few times that I would have loved to have written about before it closed early this month. Eluding Capture: Three Artists from Central Asia, curated by Jessica Chen, brought work from a region that is persistently overlooked. Central Asia has long been a loosely defined place where different cultures, languages, and ethnicities filled a vast space that didn’t acquire the modern overlay of borders and state structures until Soviet cartographers started drawing them in the 1920s.

It included a film by Uzbek filmmaker Saodat Ismailova, 18,000 Worlds (2023), which explored the ideas of 12th-century Sufi philosopher Shihab al-Din al-Suhrawardi, who believed the material world was just one of thousands of illusory realities. The film lingers on images of the Soviet Baikonur Cosmodrome, wanders over courtyards and walls of old cities, around rivers and deserts. It ends in a long-extended fade out that suggests a very deep dive into a very deep river of meaning.

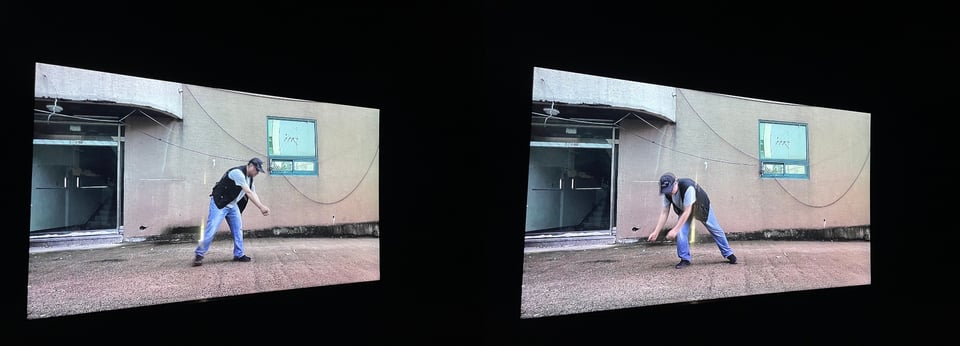

The work of Alexander Ugay considers the lives of the Korean diaspora in the region, and the way many people there — including the artist himself — spend part of the year as guest factory workers in South Korea where they make enough money to support themselves through the rest of the year. His film More than a hundred thousand times (2020) shows some of these workers recreating the motions they perform on factory floors, creating a ghostly pantomime in streets and towns of a place that is just one where they don’t perfectly fit.

But perhaps the center of the show was a series of 75 works from Kazakh artist Gulnur Mukazhanova commissioned by the museum. Each is a portrait-sized panel of colorful stretched felt, with the layers of fabric pulled out with a steel comb and raked into unique patterns of colors and shapes. The inspiration for the series of “portrait-reflections” for the Berlin-based artist were the crisis in her homeland in January 2022, when the state violently suppressed protests against the rising cost of living. The pieces are an evolution in traditional Kazakh textile art, though pointedly not of the decorative sort that since the Soviet period has been elevated by state authorities as the authentic cultural production of the Kazakh people. In it subtlety and variety, and commitment to chance and process the images, arranged like a hall of portraits, suggest the confident abstraction of midcentury Western painting.

But ultimately, it is all about the process, the idea that even now things come into being and are not defined as we think. As one wandered around Mukazhanova’s felt images, some drew you in and others you passed by. Some featured colors that leapt out, in others the very fabric was pulled out and broken like worn out pants. But it is all part of the total effect. It occurred to me some of us have a hesitancy to create imperfect things, as if it were a betrayal of craftsmanship to add to the disorder all around us. I’ve been thinking about that a lot so far this year, as I’ve puzzled out how to finish this first issue of 2025. Best to just let go, there will be another chance soon enough.