McKinley, Tariffs, and Trump - #6

How a bronze monument in Adams connects Gilded Age protectionism to today's trade wars… and the personalities of two very different presidents

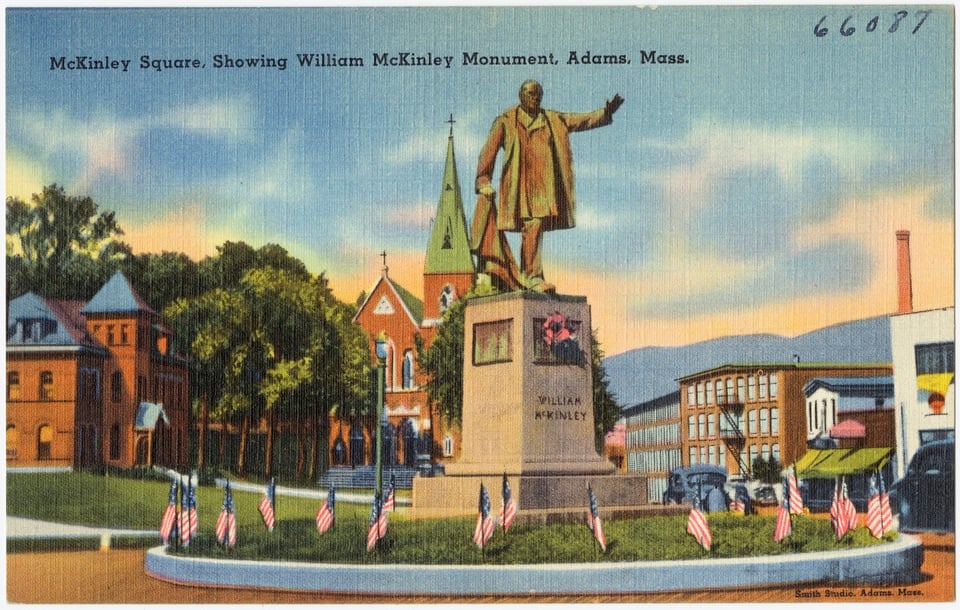

One of my first assignments for the Eagle was in October 2003 to cover a centennial rededication ceremony of the statue of William McKinley in the center of town. Town officials got all dressed up in Gilded Age finery, and they even brought an impersonator over all the way from McKinley’s hometown in Ohio. An organizer of the event told me they planned it because they couldn’t believe how few people knew who the statue was.

I've been thinking about the statue this week as our national political psychodrama landed on Tariff Week, with debates from the late 1800s suddenly reemerging. Today the statue still stands opposite the Free Library, capturing the president in oratorical rapture. But why he's there is as strange as how the current president decided McKinley was a genius ahead of his time.

McKinley, a Republican from Ohio with deep ties to Northeast money, engineered a major tariff bill in 1890. It wasn't just a blunt instrument to protect native industries, but also a tool that gave the president power to establish "reciprocity" with specific nations and goods (since everything echoes, the subsequent Republican refusal to negotiate with Canada was suspected to be a plot to annex Canada). It wasn’t the pure protectionism hardliners thought necessary to protect America’s fragile infant industries — many realized America was already an industrial world power and free markets were more important. Even McKinley eventually came around.

In Adams, the impact was immediate for the Plunkett family, who had just opened their first textile mill. With English competition priced out, they made a fortune and built more mills, eventually employing nearly half the town's workforce. But for almost everyone else it was a disaster. Prices soared, trade wars followed, and the economy staggered. Republicans got washed in the 1890 elections — even McKinley lost his seat. But the Plunketts were personally grateful, and struck up a personal friendship with McKinley. In 1892 when he had become governor of Ohio he visited Adams for the first time. After getting elected president in 1896 he came two more times and stayed at their mansion. Each visit in 1897 and 1899 was a huge even in the northern Berkshires. In 1899 he told the crowd he was “wholly unprepared to witness its splendid progress and prosperity,” and wished the crowd “increased prosperity in your mills and workshops and contentment in your homes.”

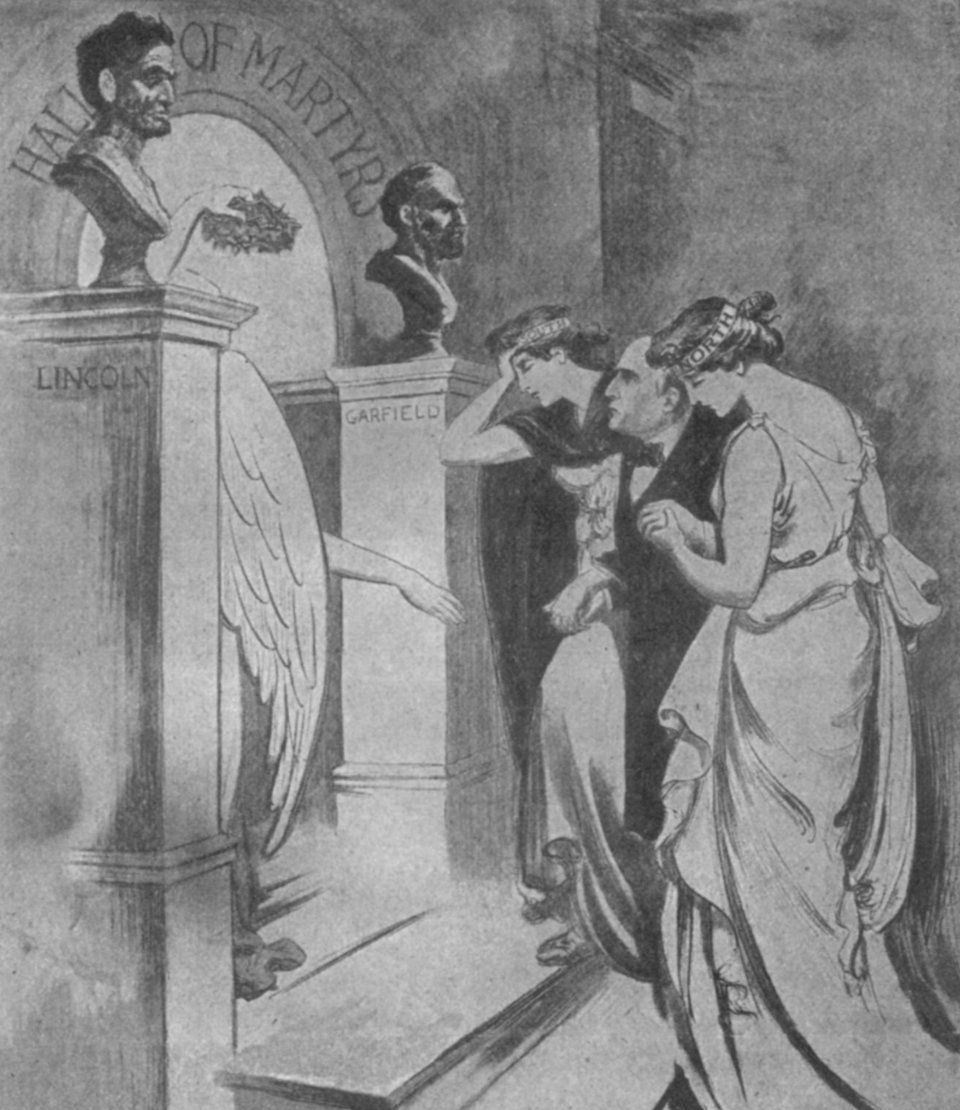

McKinley might be remembered as more transformative if he hadn't been assassinated. While greeting people at the Pan-American Exposition in Buffalo, a native-born anarchist shot him. A huge wave of grief and monument building followed (check out his mausoleum in Canton). As the statue outside his tomb reads, he was “a statesman singularly gifted to unite the discordant forces of government and mould the diverse purposes of men toward progressive and salutary action.” Of course, none of that applied to Blacks consigned to Jim Crow oppression, dispossessed Native Americans, and Filipinos uninterested in trading one colonial power for another.

The Plunketts paid for a statue unveiled in October 1903, and it instantly blurred into the background. But a closer look at the bronze bas-reliefs around the pedestal tell an interesting story. One shows McKinley driving a cart at the Battle of Antietam, another his inauguration, and a third, most notably, celebrates his tariff victory in 1890.

If you go around back, you’ll notice his hand rests on a pillar draped with a flag—actually a fasces, the Roman ceremonial staff that symbolized state order in Neoclassical design and was later adopted by Mussolini's fascist movement.

McKinley faded from memory because he wasn't particularly interesting — he was devoted to his epileptic wife, and by most accounts was simply a decent and kind guy. As such, he was overshadowed by the giant personality of his flamboyant successor Teddy Roosevelt, and the big thinking of Woodrow Wilson’s vision of internationalism. There have been attempts to revive his memory — Karl Rove wrote a book in 2015 celebrating him as a model of GOP hegemony — but nothing really stuck until now.

Trump somehow decided McKinley is his presidential role model. “President McKinley made our country very rich through tariffs and talent,” he claimed at a rally. “He was a natural businessman.” It would be interesting to know who introduced him to this idea, but surely no deeper thought went into it. In personality, Trump is miles from McKinley — bombastic and resentful, enriched by family money and tactical bankruptcies. This admiration could be as basic as that McKinley was the last president to really add territory to the map, as Trump fantasizes about Greenland and Canada.

McKinley's economic order lasted until the Depression. After World War II, different leaders with different politics built a new one with the U.S. at center — which Trump is now dismantling to enrich himself and billionaires. The McKinley statue's fourth panel quotes his Pan-American Exposition speech: "Let us remember that our interest is in concord not conflict and that our real eminence rests in the victories of peace not those of war." How quaint.