Thomas Paine, Englishman

The American Revolution was an event in British history. Remembering the English roots of revolutionaries like Paine helps put the story in its transatlantic frame.

250 years ago last Friday, the first copies of Thomas Paine’s Common Sense went on sale in Philadelphia. In a certain shorthand version of the American Revolutionary story, it was the pamphlet that changed the world. Paine’s total disdain for the vaunted British constitution, and his knack for a rhetoric that combined the exalted with the earthy, finally freed the patriot colonists from a sort of imperial spell. Having read (or more likely, heard someone else read) Common Sense, they were ready to declare their independence.

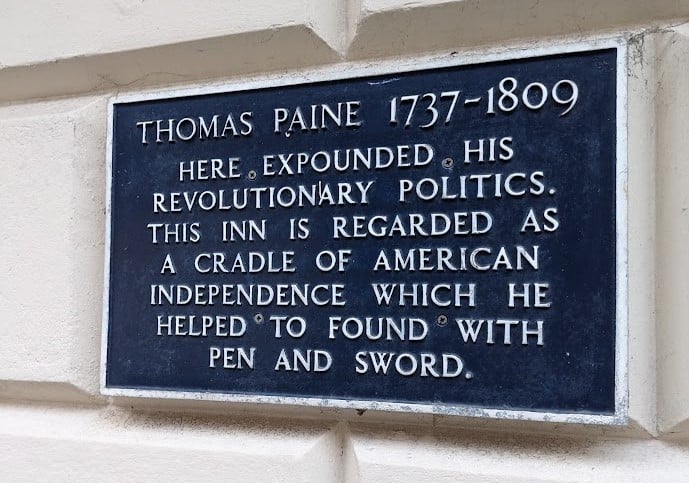

To celebrate the anniversary, I was in Sussex for the Institute for Thomas Paine Studies’ “Common Sense at 250” conference. Paine lived in Lewes for a few years, mostly while working as an excise officer, before he decamped to Pennsylvania in 1774. Now, the house he lived in (first as a tenant, then as proprietor, having married his landlady’s daughter) is being transformed into a heritage site promoting Paine’s significance, his democratic ideas, and his thoroughly English roots.

In truth, my own paper went slightly against the grain of the proceedings. It dealt with the Welsh polymath and dissenting preacher Richard Price, and his own 1776 pamphlet, Observations on the Nature of Civil Liberty. Far less well-remembered today, Price hugely outsold Paine in Britain that year. The success of the Observations shaped discourse in the metropole such that Common Sense barely got a look-in. And it was “Dr Price’s tract,” not Paine’s, that James Aitken took inspiration from when he conceived his plan to burn down Portsmouth Royal Dockyard.

Price’s pamphlet lacked two of the features that made Common Sense stand out in 1776: its furious condemnation of “the evil of monarchy” and hereditary succession, and its confident call for total colonial independence. But what Price did offer in Observations was a reminder to British readers that most of the same injustice and oppression that was motivating American anger applied just as much to people “in this country.” Price saw in the American crisis the chance for a “revolution in the affairs of this kingdom,” one that could purge corruption and reform the constitution on the basis of more equal liberty.

The focus of Price’s work, in other words, was on the struggle shared by revolutionaries on both sides of the Atlantic. Rather than advocating the separation of the colonies, he saw the crisis as a moment for empire-wide transformation from below. According to sneering critics, his ideas were soon taken up by London’s working-class rabble — and by “female patriots,” too. Aitken was just one of many who associated Price with the revolutionary project of redistributing power.

Placing Thomas Paine in his Sussex surroundings, and in the wider struggles he took part in since the 1750s (as we heard from Gregory Claeys, the new Princeton Collected Writings makes a swathe of new attributions to Paine in the decade before Common Sense), helps make the point that the American Revolution was an event in British history, not just the birth of the United States. If colonial independence was the most notable outcome of the crisis, Price and Paine both belonged to a transatlantic movement whose real goal was something else: political liberty.

For the rest of 2026, I’m hoping to write at least two entries per month here. The next will be on the changing meanings of “revolution” itself, stimulated by Dan Edelstein’s recent The Revolution to Come. Please subscribe if you haven’t already, and share this newsletter with others. Empire Ablaze is coming this July, from Verso.