This book made me physically dizzy, and now I get to publish it

Announcing Cursed Morsels' strange March 2025 short story collection release, plus a free ebook

Announcing D. Matthew Urban’s Shaky Pictures of Vanished Faces, a collection in which characters twist in the grip of forces and processes beyond their understanding—forces as anonymous as the grind of capitalism, as intimate as the gravity of desire; processes as sudden as a short circuit in a neural implant, as ancient as the turning of the seasons. Infused with the weird and uncanny, ranging from cosmic horror to exurban folk horror to dark science fiction, these stories probe the crannies and dead ends where human intentions collide with the implacable, where even the most familiar faces are liable to change, waver and fade.

If you don’t yet know D. Matthew Urban, he hails from Texas and lives in Queens, NY, where he reads weird books, watches weird movies, and writes weird fiction. His stories have appeared or are forthcoming in No Trouble at All (Cursed Morsels Press), Split Scream Volume 4 (Tenebrous Press), and Monster Lairs (Dark Matter INK), among other venues. Find him on Twitter @breathinghead or on the web at https://dmatthewurban.com.

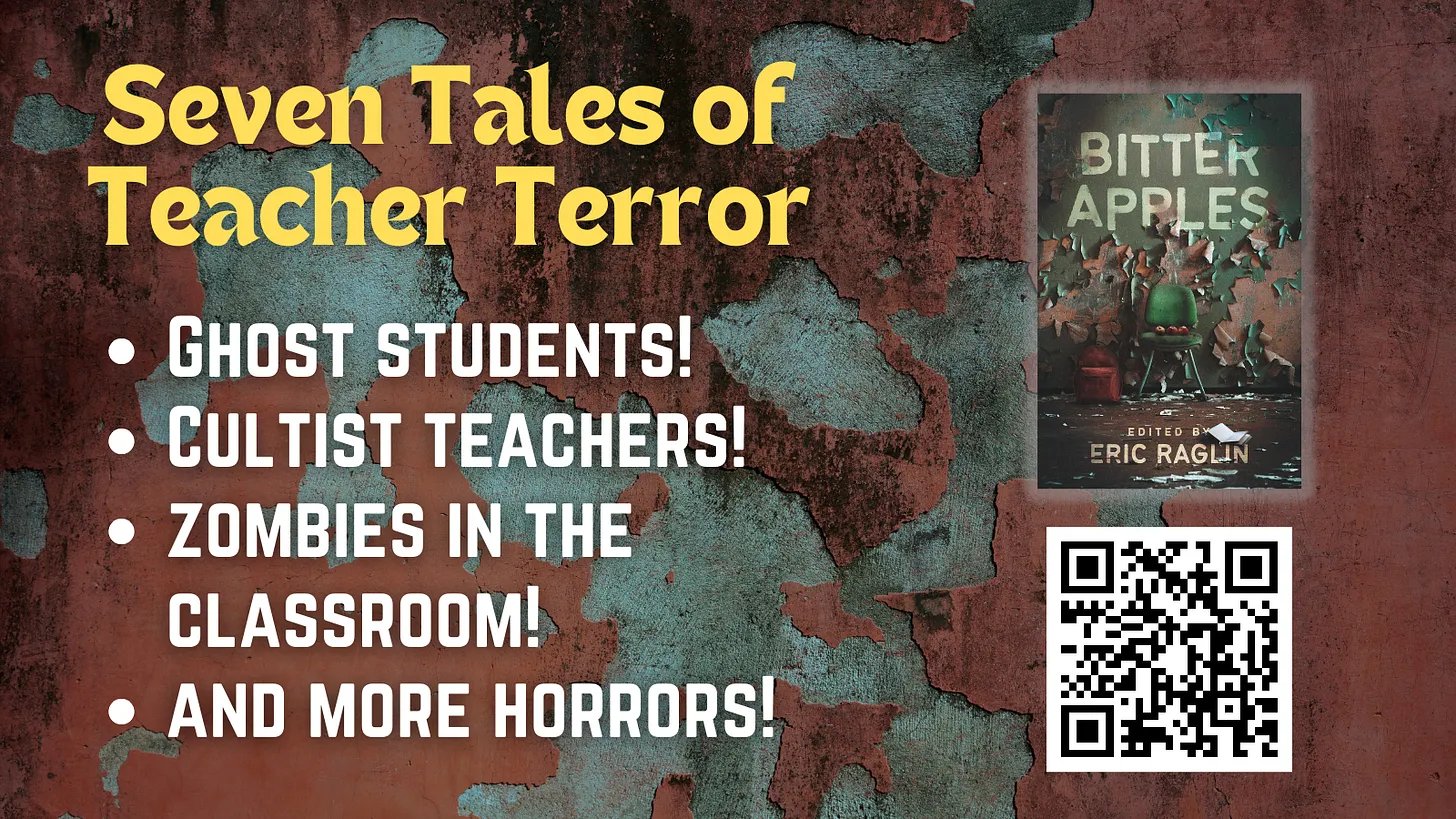

Keep reading for an interview between Dave and Eric Raglin, owner of Cursed Morsels Press, about disorienting fiction, the fragility of the human mind, and the weird joys of insects. At the end, you’ll also get a free download of Bitter Apples, an anthology of teacher horror, which features Dave’s story “The Consultant’s Hand.”

Interview with D. Matthew Urban

Eric Raglin: I love the title of this collection—Shaky Pictures of Vanished Faces. Could you tell us about how you chose this title?

D. Matthew Urban: I brainstormed a long list of potential titles, most of them terrible. This one seemed like a good fit for a couple of reasons. Many of the stories in this collection deal with horrors that unfold both outside and inside, both in the world of the story and in the lens of language and consciousness through which we see that world, and I thought it would be cool to have a title that reflected that twofold strangeness. I liked the idea of a picture that shows something weird and disturbing, but shows it in a way where you’re not quite sure what you’re seeing; you have to squint and use your imagination. And on a more literal level, faces do vanish in a number of these stories, often gruesomely.

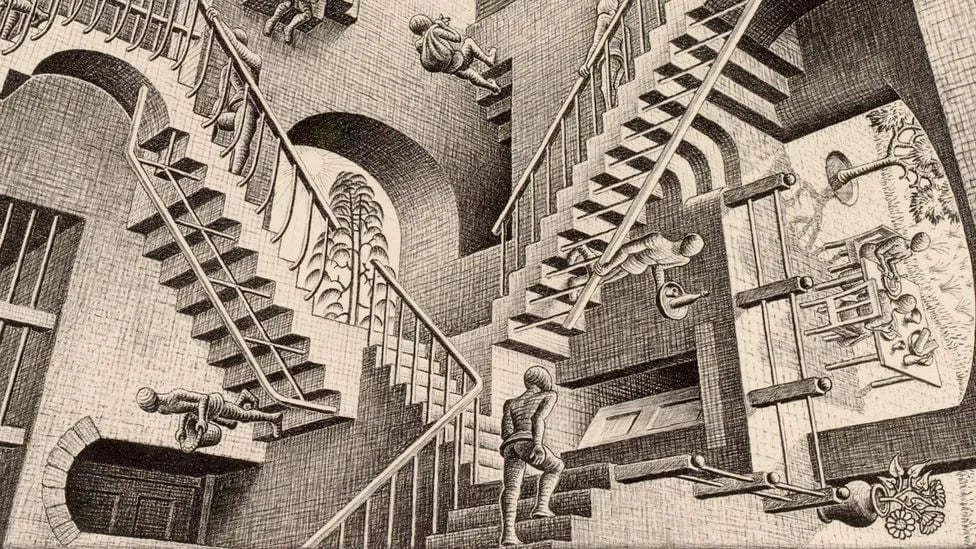

ER: I’ve read lots of disorienting fiction, but it’s rare to read something that makes me physically dizzy. Several stories in your collection did exactly that. How do you craft stories to achieve this effect?

DMU: I love fiction that leaves me feeling off-balance, so it’s great to hear that my own writing induced that sense of vertigo!

Most of the stories in this collection focus on characters who are caught up in strange predicaments they can’t understand; in the rare cases where there’s an explanation for what’s going on, the explanation doesn’t do any good for the person experiencing the horror. That experience is what I tried to capture, the feeling of being unmoored from ordinary reality. I wanted the writing to embody the weirdness instead of containing or contextualizing it, so if there’s exposition or backstory, it often comes in the form of fragmentary memories, dreamlike flashes. The narrative shifts and escalates without warning, following a nightmare logic.

Within that nightmare, I tried to stay close to the character’s immediate thoughts and sensations, not just sights, sounds, smells, but also interoception, the sense of what’s going on inside the body. “Flesh Advent” follows a runner through a long-distance race, going into detail about the natural and supernatural processes playing out inside him; I drew on sense memories from my time as an extremely mediocre cross-country runner to try to convey what it feels like to push your limits in that way. In other stories, I wanted to evoke the unsettling physical sensations that come with overwhelming emotions: terror, confusion, fascination, desire. These highly specific moments play out against the shifting, uncanny background of the narrative; if it works, that combination of the concrete and the unknown generates the off-kilter effect I’m chasing.

ER: Several stories in your collection focus on losing the ability to comprehend reality and contending with the mind’s fragility. What draws you to narratives in which characters’ worlds and even selves become incomprehensible?

DMU: I’m fascinated by how the human mind constructs a predictable world out of the flux of reality, and by the many ways in which that construction can fall apart. We build our lives around things we think are stable; what happens when that stability crumbles? A number of these stories start from a point of breakdown—a warping of perception in “Estrangements,” the death of a spouse in “The German Cousin”—and the narrative unfolds as a kind of contagion, with the breakdown spreading and deepening until the whole world seems chaotic and alien.

I’m drawn to this sort of narrative for a couple of reasons. I think reality is fundamentally strange and elusive; all the categories we impose on it are provisional. So there’s a special appeal in stories where those conceptual lenses get smashed and shattered. Even when the story ends in total mayhem, I see a weird beauty in the process of flux and transformation, a sense of the creative as well as destructive potential of chaos, which I hope comes through for the reader. Also, worlds in collapse are just fun to write about, especially when the consciousness of the describer is also collapsing. You get to play in the ruins.

ER: Some stories in this collection (“Exuviae” and “Winter Savory”) almost feel like anthropological studies of societies and families that operate in bizarre, sometimes difficult to comprehend ways (at least from my perspective). What I love about your approach to these stories is that you immerse us in their worlds without much judgment or explanation of how these societies and families operate. Could you tell us more about your approach to exploring societies and families like these ones in your fiction?

DMU: I’m glad you compared them to anthropological studies, because in those stories I was hoping to convey the sense of how a particular social group operates, its key practices and relationships; some aspects were inspired by actual anthropology books, The Dawn of Everything by David Graeber and David Wengrow, and Homo Necans by Walter Burkert. But instead of being described in a supposedly objective way by outsiders, the groups in these stories are shown from the inside, through the eyes of characters who are participating in their practices for the first time. In that sense, these are stories about rites of passage, initiations. The main characters start out confused and afraid, fixated on the strange, off-putting details of their surroundings, but as the narrative continues, they become more and more deeply enmeshed, gradually internalizing the values of the group they’re joining.

In depicting these groups, I wanted to blend the homely with the bizarre. “Winter Savory” is seasoned with memories of real-life family gatherings, though of course no resemblance to actual holiday festivities is intended. “Exuviae,” fantastical as it is, draws on the feeling of being an awkward kid at a big family get-together, surrounded by distant relatives you’ve never met. Along with those textural details, I wanted the weird groups in these stories to present an oblique reflection of familiar realities—power dynamics within families and communities, the way beliefs and practices get perpetuated as “just how it goes.” But I tried to keep those thematic concerns muted; as usual, my goal was to evoke and embody these strange worlds, not explain or moralize them.

ER: Given that Cursed Morsels publishes anti-capitalist and anti-fascist fiction, it should come as no surprise that your collection includes some stories that deal with the cruelty and incomprehensibility of capitalism and power hierarchies. What makes Weird fiction uniquely suited for exploring these forces?

DMU: Weird fiction is great at conveying what it feels like to live in a precarious world, menaced in unpredictable ways by powers whose whims you’ll never fully comprehend. That’s the sort of world that capitalism and other oppressive systems create, one where arbitrary hierarchies are reinforced by bizarre rituals and exemplary violence. A lot of excellent horror fiction takes on these issues—sometimes explicitly, like Alison Rumfitt’s brutally unsparing anatomy of transphobic fascism in Tell Me I’m Worthless; sometimes more implicitly, like the hellscape of late-capitalist alienation and degradation in Kathe Koja’s The Cipher.

In my collection, systems of oppression and exploitation make themselves felt through their uncanny, destabilizing effects on the characters’ worlds. In “The Consultant’s Hand,” budget cuts unleash a blend of cosmic horror and academic corporatization that falls heaviest on the most exploited members of academia, adjunct faculty. In a more surreal, indirect vein, “Dreamland Coffee” evokes the anxiety of being subjected to forces that run roughshod over your humanity, giving a new meaning to the phrase “downwardly mobile.” But it’s not all despair and abjection; there’s at least one story that could be read as a triumph of the downtrodden over the class oppressor, though it’s a triumph that leaves a bitter taste in the mouth.

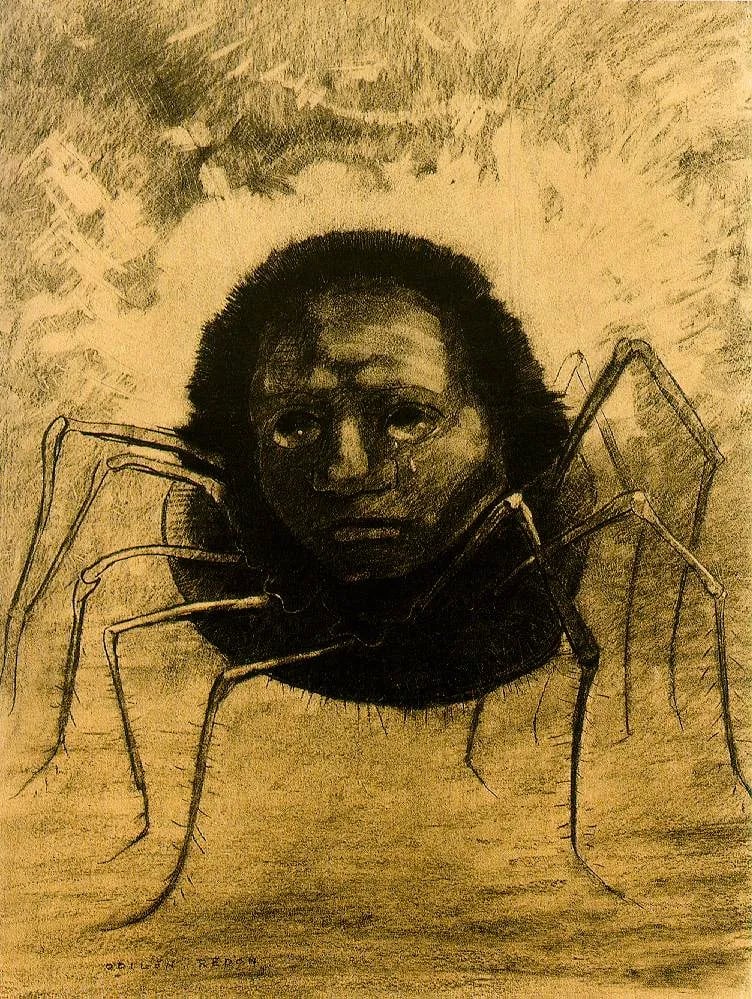

ER: Anyone who reads this collection will recognize your love for insect horror. What draws you to this subgenre? Why do insects fascinate you?

DMU: I’ll start with the part of the answer that makes me sound semi-adult. The insects and insect-adjacent critters I’m most drawn to are the ones with intricate societies or artistic-seeming behaviors—bees communicating through dance, spiders spinning webs, wasps building elaborate nests (as in the story that introduced me to insect horror, Robert McCammon’s “Yellowjacket Summer”). Combine those behaviors with the omnipresence of bugs, and you get a world full of inhuman societies operating all around us, little alien artists plying their craft. You can’t help but wonder what all that activity means to the creatures carrying it out, what their intentions are. There’s a great quote from the science and nature writer Loren Eiseley: “Spider was circumscribed by spider ideas; its universe was spider universe. All outside was irrational, extraneous, at best, raw material for spider.” As someone who loves reading and writing about worlds and ideas cracking open to reveal the irrational, extraneous outside, I’m intrigued by the parallels between human life and ”spider universe.” What weird metamorphoses might our own universe be raw material for?

The other part of the answer is that bugs are cool little guys and I love them. My attitude is captured in the opening of “A Goodnight Kiss from Aunt Spider,” where the main character watches in fascination as a garden spider kills and cocoons a grasshopper. I actually had a terrible fear of spiders as a kid; I got over it and am now pro-spider, but I still feel a tiny, ghostly twinge of dread when something starts scuttling around on too many legs. This only makes the fascination stronger, of course.

ER: A number of your stories deal with strange, often authoritarian, sometimes distant relationships between parents and children. What do you find most interesting about these complicated family relationships?

DMU: I think what interests me most is the mismatch between what our culture tells us a family is supposed to be like and the much messier, more ambiguous reality. Even in the seemingly happiest families, there are emotional complexities and strange dynamics that words like “love” and “stability” can only smooth over. In one of my stories, the narrator undergoes an awful, terrifying experience at his parents’ insistence, and when he asks them years later why they made him do it, they say, “Because we love you.” They’re not lying; it’s just that “love” can mean so many things, not all of them good. And of course you can never tell what a family is like from the outside. In another story, the narrator goes into someone else’s house, sees what’s in there, and thinks, “I’m not sure what I expected, but it wasn’t this.” Sometimes you step through someone’s front door and into another world.

ER: What types of readers will most enjoy Shaky Pictures of Vanished Faces?

DMU: Readers who enjoy getting dizzy, I hope! Readers who like it when weird fiction and cosmic horror and body horror and who knows what else all get smeared together on the same disintegrating canvas. Readers who see a fungus taking over an ant’s brain and think, “Hey, why not?” Readers who think Foucault was onto something when he wrote, “There were those for whom glory and abomination were not dissociated, but coexisted in a reversible figure.” Readers who like stories that self-destruct.