Lust! Violence! Yearning! Grief!

Announcing Cursed Morsels' exciting January 2025 short story collection release, plus a free ebook

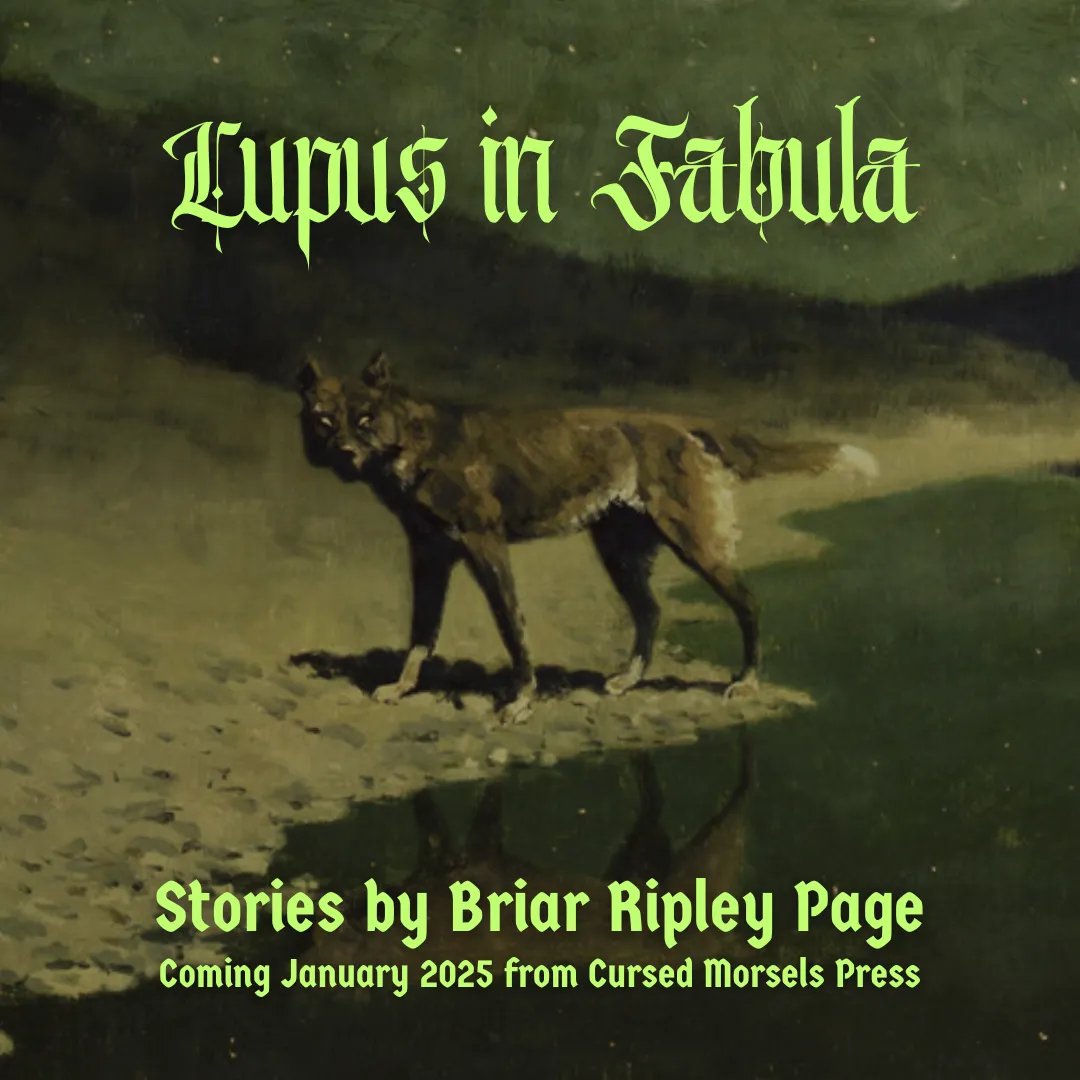

Announcing Briar Ripley Page’s Lupus In Fabula, a collection of thirteen stories about the interplay of lust, violence, yearning, and grief; about monsterfucking and becoming a monster; about transformation; about strange occurrences in sad, mundane lives.

Briar Ripley Page writes short stories and novellas, including Corrupted Vessels and The False Sister. Originally from Appalachia, he now lives in London with his partner, two cats, and other family members. Lupus in Fabula will be his first full-length collection.

Want to know more about Briar’s influences, creative processes, and general brilliance? Keep reading for an interview between him and Eric Raglin, owner of Cursed Morsels Press.

Interview with Briar Ripley Page

Eric Raglin: When you sent me your collection Lupus in Fabula, you mentioned that it’s “a little bit Clive Barker, a little bit Poppy Z. Brite, and a little bit Kelly Link”. Could you tell us more about the influence these writers have had on your work?

Briar Ripley Page: (Note on PZB: Poppy Z. Brite is a trans man named Billy Martin. I am here referring to him as Poppy Z. Brite because that still seems to be the name he associates with his previous work as a novelist and short story author, but I don’t know what his explicit preference is; I’m not trying to deadname anybody!)

Barker, Brite, and Link are three authors whose work I discovered when I was about fourteen, and who immediately blew the top off my skull and made me wish I could write similar stories. With Barker and Brite, it was this heady combination of eroticism, often unapologetically queer eroticism, and the grossest, most graphic violence and gore I had ever read. But neither ever seemed like he was just cynically trying to gross the reader out, like, say, Chuck Palahniuk or someone; instead, both authors offered something completely wide-eyed and earnest in its grotesquerie and horny awe. As an adult I think Barker’s prose often leaves something to be desired, but his body horror and monster concepts are top tier, second to none, fabulously creative and lovingly, nauseatingly detailed. You can really tell he’s a painter with a strong visual imagination when he’s describing these creatures! And Brite’s prose, conversely, is lush and gorgeous, ornate without forsaking clarity and accessibility. It’s incredibly impressive to me that he was only in his early to mid twenties when he wrote his most well-known works. You can sort of tell in his focus on young characters, in the occasional moment of what appears to be unintentional authorial naïveté or faux-jaded posturing. But you’d never guess it from the quality and style of his prose.

Link influenced me in different directions: what astounded me as a teen were her story structures, her casual mingling of kitchen sink realism and surreal magic, and the way she didn’t feel the need to explain the supernatural things that happened in her stories, imply consistent supernatural “rules,” waste time on characters in these mundane/realistic settings going “but how can this be? It’s impossible! I must be crazy!” or any of the other things I was used to in fantasy and horror fiction at fourteen. I remember being so excited by “The Girl Detective,” which is partly a postmodern/metanarrative exploration of this Nancy Drew archetype and partly a hardboiled retelling of “The Twelve Dancing Princesses,” and by “Lull,” which has nested stories-within-stories and odd chronology, and which is subtle and indirect enough that I had to read it multiple times to really understand what was happening.

There are lots of other writers I liked when I was in eighth or ninth grade who I still like today, and there are writers I read today who I’d say I now enjoy more than these three. But if I’m looking at which authors have had the most enduring influence on what I write and, especially, on how I write it, it’s probably Barker, Brite, and Link.

Oh yeah, and all three taught me an additional lesson: never be afraid to give your characters weird, stupid names. Forget consistent nominal realism. You can have a Joe Allen in one story and a Birdie Ovaltine in the next. Or they could even be in the same story! Just own it.

Your collection is great for readers who appreciate horror, Weird fiction and romance. How would you describe your creative approach to blending these genres? How do the horror and Weird elements interact with the romance elements, and vice versa?

As mentioned in the previous question, two of my early influences were Clive Barker and Poppy Z. Brite/Billy Martin! I also loved Anne Rice as a young teenager, and Tanith Lee. Horror and romance/eroticism always seemed to go together naturally, like peanut butter and jelly; it was never something where I had a big “eureka” moment, or even something I thought much about. I was slightly too old for Twilight— I was in high school when it came out, and already turned on to all this other, older, more mature stuff. I can imagine getting really into that type of toothless YA paranormal romance if I’d been two or three years younger, not realizing that there were better, far less diluted takes on similar themes out there. That would probably have resulted in more of a voyage of discovery for me. I’m definitely a romantic, but the horror and strangeness in a story can’t be defanged and domesticated or I eventually lose interest. The sense that a monster is really alien and lives according to a totally different moral code, or is really dangerous and will actually hurt you; characters encountering totally disgusting situations or being rendered abject and then brought back from that state changed and transformed; the presence of deep, dark, complicated emotions; bizarre, partially explained or unexplained shit that makes you think “what the fuck just happened?! I’m so upset right now!”— those elements are what make this type of story so compelling to me. They make the romance seem alive, meaningful, and seductive.

I appreciate that your stories often follow characters who lead relatively mundane lives, following everyday routines, doing working class jobs, etc. For you, what’s the importance of fiction that focuses on mundane lives rather than grandiose ones?

Almost everyone has a mundane life, one where they don’t work a glamorous (or even interesting) job and aren’t rich or famous or super special in any particular way. Even when you’re writing fantasy and horror, the story is going to connect with readers more emotionally and personally if the characters deal with some realistic, relatable problems in addition to more esoteric and exciting monster or magic-based problems. When I write characters with jobs, they tend to be jobs I’ve actually done or jobs people close to me have had so that I can write about them with verisimilitude sans research.

I spent a few years in my early to mid twenties as a janitor and hotel maid, and those jobs have disproportionately inspired my fiction because they actually are interesting! Really tough and unpleasant a lot of the time, but interesting. Once I found a whole, rotting, maggot-encrusted steak in the wastebasket of a music practice room on the college campus where I was working as a janitor at the time. To be honest, I think everyone who’s physically able to should do some work of this type as a young adult. It makes you a lot more conscientious and considerate about the messes you leave for others, it cures you of any squeamishness you might have about bodily fluids, decay and rot, gross textures like wet hair, etc. If you write horror, it will give you ideas.

In the past couple years, we’ve seen a few works of fiction and film that engage with the character of Renfield from Dracula. Your own take on Renfield’s story is included in this collection. What draws you to his character specifically?

I first came to love Renfield because of Dwight Frye’s exuberant performance in the 1931 Dracula movie. He’s famous for doing the unhinged “YESSSSS, MASTER!!!” thing, but before he gets to that part of the performance, we get to see him as a nervous, naive, soft-spoken young man. In this version of the story, he’s the solicitor who gets sent to Transylvania to help Dracula prepare for his move to England, instead of Jonathan Harker. And the movie really goes all-in on the homoerotic subtext of Dracula seducing Renfield. After a shot of blood drinking that frankly looks more like a deep, passionate kiss, we cut away, and the next time Renfield appears he’s completely insane! Dracula is just that good, I guess.

This depiction primed me to like Renfield in the novel, where he’s a really different character in a lot of ways. In the book, his madness predates contact with Dracula, but makes him a lot more receptive to the Count’s influence. I thought that was a neat concept. I don’t think his psychosis is depicted very realistically, but for the time period, and considering that Bram Stoker isn’t generally an author given to moral nuance, it’s impressive how sympathetically he comes across and how much depth he’s allowed to have as a character. Even today, mentally ill characters are often just treated as boogeymen.

Your story “Therianthrope” was originally published in The Book of Queer Saints, an anthology edited by Mae Murray with a focus on queer villains. Lupus in Fabula has no shortage of villainous and morally complex queer characters. For you, why is it important to create stories that focus on these seedier characters? And do you have some personal favorite queer villains in fiction or film?

Personally, I’ve always found…not necessarily even villainous characters, but monstrous or antiheroic ones…a lot more interesting and a lot easier to relate to as vehicles for emotional catharsis than conventional heroes. While a situation where queer people are only depicted in fiction as monstrous or damaged or unhinged is obviously no good, I think making it taboo for characters from a minority group to be bad or violent or evil or even just “problematic” in some of their behavior is equally dehumanizing. People from any group can be any kind of thing a person can be, and fiction should reflect this.

One of my favorite queer villains from fiction who doesn’t get much attention is Frank Cauldhame from Iain Banks’ The Wasp Factory. Frank is a misogynistic teenage ex-serial killer (he stopped because he got bored) and a sort of trans man, although (spoilers for a forty-year-old book) this last part isn’t revealed until the novel’s Shocking Twist Ending. This is definitely not a politically correct, accurate, or inoffensive depiction of transness, but it was one of the first times I encountered an explicitly transmasculine person in fiction, and Frank’s voice is so distinctive, slimy, poetic, and dryly hilarious. He’s sort of like a boy version of Merricat Blackwood from We Have Always Lived in the Castle (who I would also count as a queer villain/antihero for her incestuous attachment to her older sister).

We’ve seen a large influx of grief horror narratives in the past decade, many of which feel rote and emotionally shallow in my purely editorial opinion. However, your grief horror stories in this collection feel fresh and engage me on a deep emotional level. What would you say makes for an effective grief horror narrative?

What an interesting question— I don’t think this is actually something I’ve given much conscious thought! I guess one thing is, I don’t really set out to “write about grief” or about any other kind of emotion or trauma or what have you. I just have characters, and a situation, and I try to put myself into the position of those characters in that situation and be realistic and unflinching about whatever emotions come up. If it’s too much for me in the moment, or if it turns out I’m not ready to write a particular story because it involves feelings I don’t have the life experience to write about vividly and truthfully, then I put it aside for a while. Grief has definitely been more on my mind over the past few years than it was in my teens and twenties. So far, my thirties have involved a lot of thinking “this is what it’s going to be like for the rest of my life. I’m going to know more and more people who are dead. People I like or love aren’t automatically going to pull through every crisis. If I live as long as my grandmother— who’s 98— I will probably witness the death of almost everyone I care about.”

Which is horrific! And it’s also inevitable, not something you can change— and what’s the alternative, anyway? Dying young, and leaving your loved ones to mourn you.

You include some wonderfully Weird (with a capital “W”) stories in this collection. I love how you leave certain questions unanswered, letting the strange elements stay strange and my imagination run wild. When writing Weird fiction, how do you decide when to reveal the answer behind a mystery vs. keep it mysterious?

It’s pretty intuitive. I reveal as much as I feel like the story needs to make narrative sense (not necessarily logical or realistic sense) and keep the reader’s attention, and not any more than that. Getting into Aickman semi-recently has been great for that; he was the undisputed king of not explaining what the hell is going on in a weird story, and almost all of his are total bangers.

Multiple stories in this collection deal with bodily transformation as a source of queer liberation, terror, marginality, and discovery. Could you tell us more about your interest in bodily transformation narratives? And why do you often explore these transformations through the lenses of horror, Weird fiction, and romance?

I’m trans, and physically disabled with a degenerative genetic disorder that means I can easily bend my joints in all kinds of ways I’m not really supposed to be able to but experience frequent joint injuries and chronic pain. These things contribute to, and probably originated, my interest in body horror transformations. They definitely influence the way I approach body horror transformations, which is usually ambivalent and sometimes unambiguously positive— medical transition has been a magical, liberating, and sometimes erotic experience for me. As much pain as my dysphoria caused me for many years, I don’t wish I had been born a cis male. I feel like I’ve come through fire to become someone with a unique perspective on the socially constructed cages of sex and gender, and to become someone who’s liberated from feeling they have to fit into specific categories, feeling they have to do XYZ to be a real man, feeling they can never empathize with or be similar to someone of a different gender or sexual orientation. Meanwhile, my connective tissue disorder is something I’d definitely rather not have, but the joint hypermobility is still kind of cool. I used to use it in amateur circus performances. I can move around like Samara/Sadako in The Ring, or like Regan in The Exorcist, or like Pretzel Jack in Channel Zero: The Dream Door.

So, I guess my lived experience lends itself to discussing these things through a lens of horror and the grotesque, but also one of excitement and fascination, of appreciation for things that are unusual or startling.

What types of readers will most enjoy Lupus in Fabula?

I think it’s going to appeal to readers who enjoy horror-adjacent fiction that’s more interested in character, emotion, and atmosphere than in providing big shocks and scares. People who enjoy eroticism, explorations of sexuality, and a frank attitude towards the human body and its various functions will dig this; people who find that stuff off-putting and uncomfortable may not. People with a sexual interest in humanoid monsters (vampires, werewolves, Mothman, etc.) should definitely read this collection!