#7: risograph zine, poems, forest inspirations

sharing creations both physical and digital

Dear creative friends,

I’m experimenting this month with sending a longer letter, but a little less frequently. I’ve been reflecting on what makes mail (email or physical mail) fun, versus a chore - it’s the added sticker that slips out of the sheet of paper, the ink of someone’s handwriting, the feeling that everything in the letter is a gift wrapped just for you. That’s what I hope these letters feel like.

Since my last letter:

I printed my first risograph zine!

I reflected on a summer of writing

I wrote two poems on my phone during a very busy season at work

And also in firsts: made biscotti for the first time (delicious!)

If you would like to comment on this newsletter, just hit reply and send me an email. I’ll write back!

Printing: My risograph zine, “Writing is a Kitchen”

A couple of months ago I wrote about a zine I tried to make that just… didn’t work. But from that failed project I salvaged one phrase: “Writing is a kitchen.” It felt instinctively true, but why? My answer to this question became an essay—about the layered pleasures of writing and baking, and how both activities allow me to revisit a formative place in my world, my grandparents’ kitchen.

And then I printed it as a small zine!

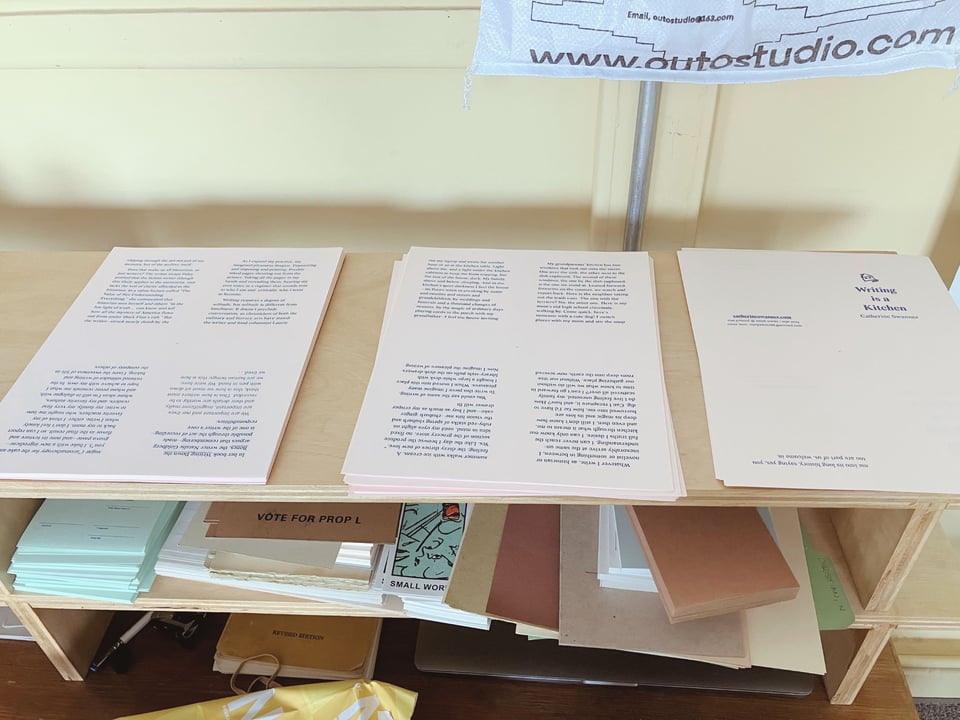

I printed the zine on a risograph duplicator at Small Works, a print studio in Detroit. A risograph lives somewhere between a photocopier and a screenprinter. (Risotto Studio, a risograph print studio in Glasgow, explains the process much, much better than I can.) After taking a couple classes in bookbinding and risograph this summer, I was excited to print something of my own.

It took me the better part of an afternoon to print the copies, cut the pages, collate, fold, staple, and trim. Precise yet meditative, the process was not unlike baking a complicated bread recipe or layered cake. I’m especially grateful to the owner of Small Works, Gerald, for guiding me through the printing process.

Nothing forces you to really believe in a piece of writing like spending four hours printing 40 copies of it. I would genuinely love to share this zine with you. If you’re interested, please pop over to this form and I’ll mail one! It’s free, and I won’t keep your mailing info.

Sharing: Creative reflections, some new poems

Over Labor Day weekend I reflected on a summer of writing and creating. I’d brought so much to completion, but I felt out of balance, like I’d immersed myself in writing at the expense of neglecting everything else: making plans with friends, cleaning my house, remembering to go for walks. The rest of the month threw me off balance in a different way — immersed in stressful projects and deadlines at my day job, I could hardly find space to hold anything creative in my head. I found respite in poems, which I could draft on my phone and wrap my mind around in fifteen minute bursts.

“Every Nuclear Family is Radioactive in its Own Way.” Initially inspired by the (unfortunate) news that New York state is shipping irradiated soil and rubble to a hazardous materials landfill in Wayne County. This reminded me of the work of Alex Wellerstein, who has been writing for a decade about “nuclear secrecy,” aka, the history of the idea that scientific knowledge about nuclear science and weapons should be kept completely hidden from the public. The phrase “nuclear secrecy” is so evocative, too, and I wanted to keep playing with it.

“In Winter.” I felt I was exhausting my usual bag of poetic tricks (which is to say, the one trick: enjambment) so I decided to try writing a series of lunes. Lunes are a poetic form invented by American poet Robert Kelly—a tercet with lines of five, three, and five syllables. What a fantastic constraint!

Reading: Trees

I’ve been reading a lot about trees lately—the investigative memoir Mill Town by Kerri Arsenault and the novel Damnation Spring by Ash Davidson both prompted me to think about the true costs of lumber and paper, and the people who pay those costs. This article in Aeon about these “forest crayons,” created by the design studio Playfool, expanded the conversation for me in new ways.

In the 1950s, Japan’s forestry board clear-cut huge tracts of old-growth forest, and then replanted trees in monocultures to seed a lumber industry that never materialized. In a quirk of the global supply chain, it’s cheaper for Japan to import timber from Indonesia than it is to use its own trees. But those forests, now all 60 or 70 years old, still have to be managed and thinned to prevent erosion. So where does all that extra lumber go?

Exploring this question from an artistic lens, the artists Daniel Coppen and Saki Maruyama, who run the design studio Playfool, ground wood from Japanese trees into a fine pigment powder, and then turned the pigment into crayons. The crayons, rather than just using up a resource, prompt new modes of understanding: “While the colour of wood is often thought of as simply ‘brown’, Forest Crayons reveals the vast spectrum of hues that exist in the forest. From the light green of magnolia, to the deep turquoise of fungus stained wood, each crayon exhibits a distinct colour determined not only by the species of tree but also the conditions in which it is grown.”

And one last thing…

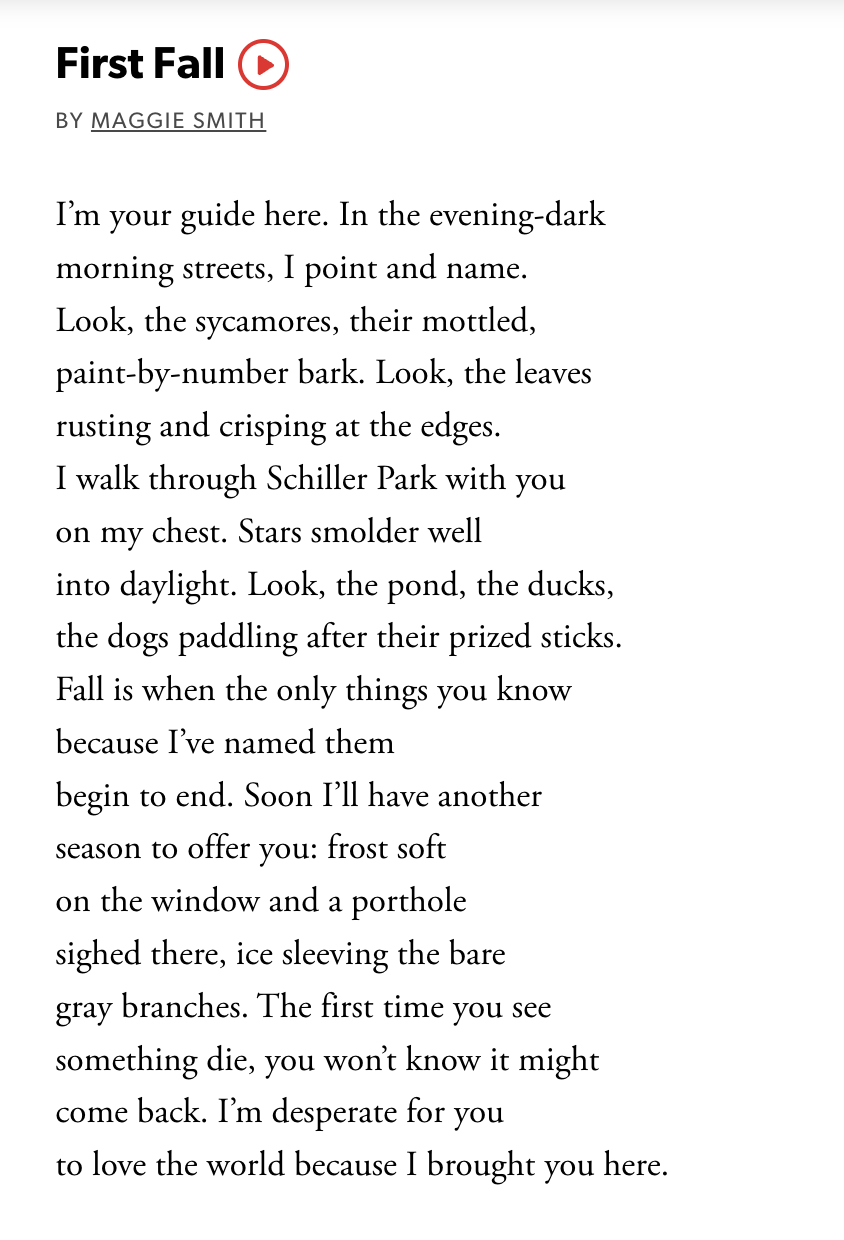

Because this week is the first week of fall, let me leave you with this beautiful poem by Maggie Smith, “First Fall”:

.

.

.

Hope this note finds you ready for the new season, and doing well wherever you may be,

Catherine