Manga Series: Case Closed, Golgo 13, Banana Fish, Lost Lad London

It's long overdue to bring manga into the crime comics discussion

For the first time in this project, we’re going to talk about another country’s comics industry: Japan and the mighty manga. I’ve read a lot of posts online about crime comics over the years. I like to see what titles are talked about, their frequency, what’s being said about them, and I’m always hoping to find a title that’s new to me. Manga rarely comes up in these discussions. This week, we’re going to finally bring manga into the crime comics conversation.

An important thing to know about manga, especially for this conversation, is that Japanese comics often run on a different publishing model than the US model. In the U.S., issues are typically published monthly then collected together. In manga, new installments are called chapters and, on average, they have different page counts. New chapters from various titles are bundled together in weekly magazines. Chapters for many titles are also quickly made available in English via various digital platforms like the VIZ or Shonen Jump App. Chapters are also collected into book form, though there can be a longer gap for them to be licensed and published in English. So new chapters of a title are typically published weekly. This can lead to a looser, pulpier, serialized feel because the mangaka (manga writer/artist) and their assistants (if they have them) is cranking the chapters out at a fast pace.

The popularity of 1947’s New Treasure Island by Sakai Shichima and illustrated by Osamu Tezuka created the modern manga industry as we know it today. Tezuka is considered the godfather of manga and it’s been suggested that he is the trunk that all manga branches from.

Due to the popularity of New Treasure Island, there was a proliferation of manga genres, including mystery mangas. Initially the audience for mystery manga was older readers of mystery fiction. Starting in the 1950’s, coinciding with a boom in the genre, manga titles were created and marketed to boys.

Even though it’s only in the past few decades that manga has become more popular and readily available in the West, the Japanese comics industry has a long and rich history all its own. Whatever I say here is heavily summarized.

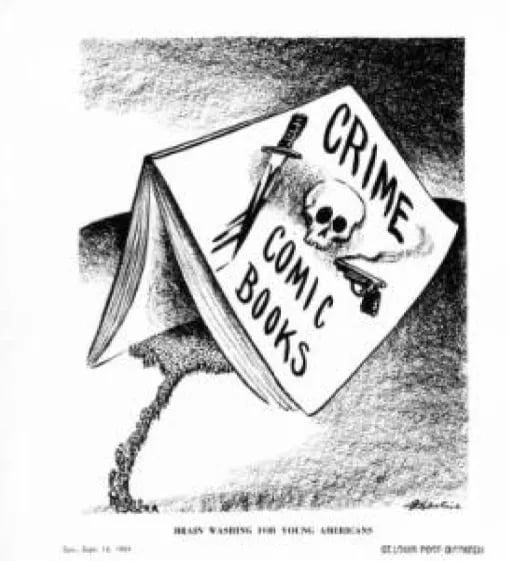

It’s also worth noting an obvious point: the Comics Code Authority, which was in place in the U.S. from 1954 until 2011 (in a diminished form), was not in place in the rest of the world. So while crime comics (which were part of the original moral panic that led to the creation of the code) were absent from the market in America, they were present elsewhere and continued to grow.

Running parallel to this is Japan’s rich history of mystery and detective fiction. Japanese detective fiction goes back to Edo period trial narratives. So when Edgar Allan Poe’s “The Murders in the Rue Morgue” and Sir Arthur Conan Doyle’s “Adventures of Sherlock Holmes” hit Japan, audiences were primed and the impact and influence of those authors and titles are still felt today. Like any genre of fiction there have been booms and lulls but we’re talking about a mystery fiction tradition that is nearly as long and just as rich as that in Europe and America.

With this post, I want to introduce a couple of manga titles that challenge the notions of longevity and popularity in crime comics that we’ve talked about already then wrap up with a a pair of recommendations.

This post is just a start. There will be more manga titles talked about in the future.

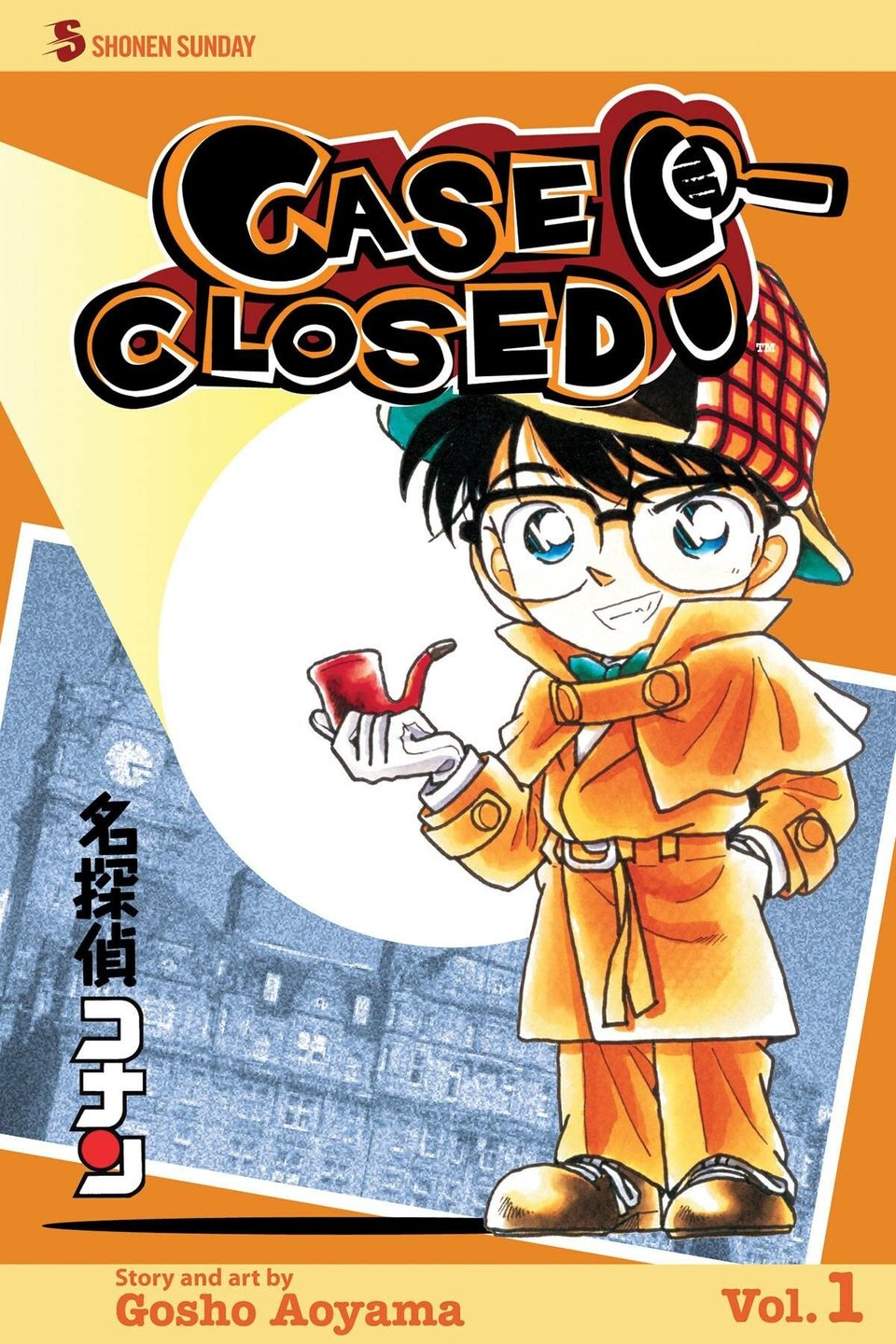

Earlier I said that “If you ask people what the greatest crime comic of all time is you will find that a consensus has basically been reached, Ed Brubaker’s Criminal.” In the first two posts about crime comic series, I also stated that they were U.S. focused. Criminal is a popular series. Period full stop. But it isn’t the most popular crime comic in the world. The most popular crime comic series in the world is Case Closed/Detective Conan and it isn’t even close.

(Just to be clear, I’m not really comparing Criminal and Case Closed. They operate in two different modes. I am just trying to expand how we think about crime comics, longevity, and popularity and I’m using one as an on-ramp to introduce the other.)

Case Closed/Detective Conan made its debut in January 1994 and is still running currently. As of April 2025, 107 volumes have been published. In 1996, the anime series adaptation made its debut and the show is still running currently with over 1100 episodes. There have been 19 anime films. It is currently available in print and on the VIZ App. There are currently over 270 million copies of the tankōbon (paperbacks) in circulation. You can go to the manga section of your local bookstore right now and probably find some Case Closed volumes.

The basic set-up and inciting incident is that Jimmy Kudo is a high school detective who solves cases and helps the police sometimes. An organized crime group known as the Black Organization try to kill Jimmy by giving him an experimental drug. The drug makes him the size of an elementary school aged child. He takes on the name Conan Edogawa (a reference to Sir Arthur Conan Doyle and Edogawa Ranpo, a major figure in the formation of the mystery genre in Japan) and has to live life as a child. He helps out a friend’s father, who is a PI and investigates and challenges the Black Organization. Case Closed balances working cases and pushing the larger story arcs forward. Japan has a rich mystery fiction history and Case Closed works in that mode. The main character uses detection, logic, and reasoning to solve cases. Plus trickery and disguises.

In an earlier post I used the TV term “limited series” to describe a certain kind of crime comics series. It might be useful to think of Case Closed like a network TV show in the U.S. Similar to network TV, Case Closed is long running, written for a general audience, mostly family friendly, and is episodic in nature (cases typically last a couple of chapters). In current TV discourse, you’ll find people lamenting some of the qualities of longer seasons of older network TV. Because the seasons were longer, writers had room for things like side character episodes or fantasy episodes. Like any other long running art form, anime and manga can have filler episodes/chapters and this is true for Case Closed also. There are episodes that advance the main, overarching plot, and there are episodes that have nothing to do with it.

Another thing to point out in terms of the popularity of Case Closed (and it’s true for other titles too) is that it’s a big world and the United States isn’t the only consumer. Case Closed is huge in Japan and very popular in other parts of the world and less so here in the U.S. It’s an easy trap for Americans to fall into thinking that the U.S. = the rest of the world when it comes to art consumption, art creation, and pop culture. (Conan O'Brien got some mileage out of discovering Detective Conan a few years ago, it’s worth checking those clips out on YouTube.) There are Chinese blockbusters, Indian rappers, and Japanese detective stories that are very popular. But you (hopefully) don’t need me to tell you it’s a big world and Americans aren’t the only one in it.

Thanks to Hollywood movies, we often have an unconscious bias. We can imagine the desert of Nevada, the beaches and woods of Rhode Island. We've seen the snow-covered upper Midwest, and the sunlit skyline of California. We see the US as a nation of variety, but the same luxury is not extended to other countries. Egypt is a desert. Mexico is also a desert. Vietnam is nothing but jungle. And Russia is always in the winter. It's reductive….In the West, we often have this impression that China is repressive and cold. And I always find that dehumanizing. Even at this world beyond worlds, people live colorful lives, as lively as anywhere else. Their languages may not cross the barrier, but their helping hands can certainly reach beyond the clouds.

I like Case Closed and read it a little bit at a time on the Viz app. It’s lighter fare and scratches that classic, traditional mystery itch nicely. Given the size of the series, hopefully I’ll finish before I retire ;)

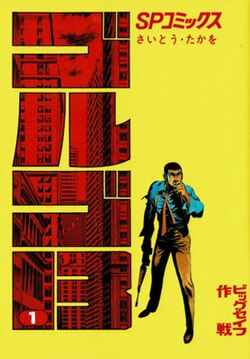

Case Closed is fully available in English translation in the U.S., Golgo 13, while undeniably popular and has been around for a long time, remains only partially available in the U.S.

Golgo 13 by Takao Saito was first published in 1968 and has continued to be published ever since, even after the author’s death in 2021. There are over 300 million copies in circulation. Gogo 13 has been adapted multiple times in various formats including two live action films, Golgo 13 (1973) and Golgo 13: Assignment Kowloon (1977), where the character was played by Ken Takakura and Sonny Chiba respectively. There are even a couple of spin-offs.

The main character is a cold, unemotional, taciturn killer. His missions take him all over the world and he gets involved in contemporaneous (as of the time of publication) current news events.

An interesting characteristic of the series is that the character isn’t always a main player in his own series. The story will often follow his target until he enters the story to complete the mission.

A Japanese institution, Golgo 13 is like James Bond without the wink: an infallible, emotionless, sexually magnetic sniper-for-hire who can assassinate anyone, anywhere in the world. — The Complete Guide to Manga by Jason Thompson

Viz Media has published thirteen volumes of Golgo 13, a selection of stories from the long publishing history. They are available on the Viz app. Given the episodic, “doing jobs” nature of the story, there is very little continuity that readers have to be aware of. Given the desire of the writer to insert Golgo 13 into what were then current events and current political figures, Golgo 13 is dated retro fun. But probably in small doses.

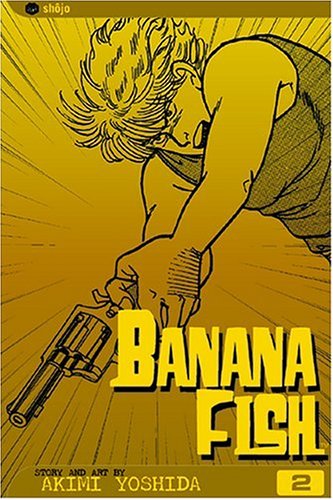

Banana Fish by Akimi Yoshida was first published in May 1985 and ran until April 1994. It’s collected in 19 volumes and is a single complete story. It is currently available in print and digitally purchased editions. It was adapted into a 24 episode anime series in 2018 which is currently streaming on Prime (in the U.S.)

“One of the great shojo manga epics.” — The Complete Guide to Manga by Jason Thompson

While not as mega popular as some of the titles mentioned so far, Banana Fish was fairly popular and has a loyal following, especially among shojo readers (a type of manga that, generally speaking, is aimed at a female audience) but doesn’t really seem to have jumped out into a wider audience. (When it comes to shōjo and josei manga, misogyny within the manga industry and fandom plays a part in keeping many of these titles from gaining a wider audience. Colleen's Manga Recs on Youtube is an excellent shojo resource that will educate and have you adding to your tbr pile.)

If you look up Banana Fish you’ll find all sorts of good information out there. You’ll find that it’s a highly regarded shojo title. It is. You’ll find that it has a gentle, beloved gay blossoming relationship at its center. It does. You’ll find that the audience is loyal. We are. But here’s what you won’t find explicitly stated. It’s an epic crime story that spans over 3500 pages.

Banana Fish is set in New York City in the 80’s with some Vietnam war flashbacks earlier in the series. 17 year old Ash is the former sex toy of crime boss Dino Golzine, the series baddie. Ash is now the leader of a street gang bucking Golzine’s control of the city. When Ash stumbles across a dying man with links to his brother who went crazy in Vietnam and a secret mind controlling government project called Banana Fish, he finds that the conspiracy goes all the way through NYC organized crime and global organized crime groups to the government and the highest halls of power.

It’s also heartfelt and tender. Ash, the young and dangerous gang leader, and Eiji , the young Japanese man he forms a bond with early on. It’s this tentative relationship that forms the heart of the story. Ash is a violent young man who has faced a lifetime of sexual abuse and rape (handled sensitively and off page). Eiji helped Ash find his humanity again. When you're human, you become vulnerable. When you're vulnerable, you can get injured and sometimes love stories are tragic.

While grounded in some semblance of reality, the entire store has this heightened pulpy edge to it that keeps all the action moving at a fast pace. And boy is there action. There are gang fights in the subway and escapes from prison and mental institutions. There are showdowns and double crosses. The cast includes gang members, crime bosses, journalists, politicians, assassins, and many more.

Banana Fish is what you hope for when you start digging into a subject looking for great works that aren’t as well known as they should be. It’s a great piece of crime fiction hiding in plain sight. It deserves more written on it and I’d like to do a longer review/deep dive on it in the future.

Initially I couldn’t decide what else to recommend beyond Case Closed, Golgo 13, and Banana Fish. I thought I might include Lupin the Third or Old Boy. Instead I decided on a more intimate, human, and small scale story, Lost Lad London by Shima Shinya. Lost Lad London is published by Yen Press and is a complete story in three volumes. It is available in print, for digital purchase, and available through some library services (Comics Plus but not Hoopla).

I also realize that I’ve created an accidentally occidental pair of recommendations. It is a natural response to be curious about other countries and cultures. Just as Americans and Europeans are curious about places like Japan or China, people from those countries are curious about America and Europe also. Just because manga is a Japanese art form, doesn’t mean that all manga stories have to be set in Japan. Banana Fish was written in the 80’s & 90’s and is set in New York, Lost Lad London was written in the 2020’s and is set in London.

Al is a young man of South Asian descent with adopted parents. He goes about his day. Takes the subway home while texting his flatmate. He’s a nice kid in his own little world. A body is discovered on the train at the same time Al was a passenger. The body is the mayor of London. Two days later, Al finds a bloody knife in the pocket of the jacket he was wearing on the day the mayor was killed. It’s not his knife. He doesn’t know how it got there. He didn’t do it. What’s going on? The answer lies somewhere in Al’s past.

Lost Lad London is rooted in character, family, and relationships. It examines class and privilege and explores trauma and prejudice. Al is of South Asian descent and the system won’t view his situation kindly. At the center of the case is Detective Ellis, a gruff Black man haunted by a past case that resulted in another brown kid’s death. He’s determined to work through his past trauma by sheer will and perfection. He tells another detective, a woman of East Asian descent, “...That all I can do now is do my job well.” This, of course, isn’t a healthy way of dealing with the past. We see him early on visiting a cemetery on the anniversary of something. So when Ellis is confronted with the idea that the murder weapon was planted on Al he’s at an emotional crossroads in his life that lets him do something he may not normally have done, help Al figure this all out.

Together Al and Ellis will get to know each other better, develop trust, and figure out what the hell is going on with the death of the mayor. Lost Lad London is a deeply human and vulnerable crime series. It’s intimate and thoughtful. I don’t know if this is the case but it’s easy to imagine Shinya being a fan of and influenced by British detective procedural TV shows.

Have you read any of these titles? Are there any manga mystery/crime titles you’d like to see covered?

You just read issue #5 of Bad Karma, Loose Ends & Stray Bullets: Exploring the World of Crime Comics. You can also browse the full archives of this newsletter.