What we get from paying attention

20 years or so ago I visited the Museum of Modern Art here in New York and saw an exhibit that I’ve never forgotten. Somewhere on the third or fourth floor there was a small room projecting a film that depicted a single scene, in super slow motion, for over an hour.

It was a moment from the Bible in which Mary announces her pregnancy (of Jesus) to her cousin Elizabeth. Elizabeth, herself pregnant with John, takes in the news, says something brief, and walks away. That was the entire scene. And if I remember right, there was no sound – at most there was an ambient drone that matched the snail-like pace of the video.

I sat, transfixed, throughout the screening. This wasn’t due to the content, exactly – how interesting is it, really, to watch a character speak a single line? Instead what engrossed me was my ability, due to the film’s slowed-down pace, to notice the tiny details – each micro-expression, each facial tic – that flashed across the characters’ faces. In particular, I could see that Elizabeth was jealous, something revealed by a passing glance that I never would have noticed at full speed. The film’s slowness conferred a heightened awareness that is nearly impossible to achieve in everyday life. It’s the experience of paying full and total attention.

I don’t need to tell you that our powers of attention are not what they used to be. Screens and apps and feeds seem to be everywhere, at work and in our personal lives, always asking us to stop what we’re doing – really, stop what we’re thinking – and start scrolling. It’s the opposite of that MoMA exhibit: instead of slowing things down, so that we can see more clearly, the devices speed everything up. As a result, we can barely perceive anything any more.

“In paying attention we pay respect,” writes Nicolas Carr in a 2025 essay. Social media thus fosters an environment of disrespect. The screens and their addictive apps, Carr says, are designed to shatter our attention:

In pushing us to assume a harried, impatient posture of perception, reflexive rather than reflective, the screen is really a means of avoiding . . . deep intellectual and emotional engagement.

One possible response to this onslaught is to decline, wherever possible, to participate. I wrote a few months ago that The Luddite resistance is here, describing the efforts of the Luddite Club and related groups to build communities of people resisting Big Tech’s predations on our attention. I still admire the Luddite approach – defaulting to “no” whenever possible.

A few years ago another community started up with a related, but slightly different, approach. The Friends of Attention and the Brooklyn-based School of Radical Attention are centered – as their names suggest – on attention (as opposed to, say, Big Tech or its addictive devices) as the topic to explore. SoRA, for example, convenes small groups to discuss, and try out, the practice of attention.

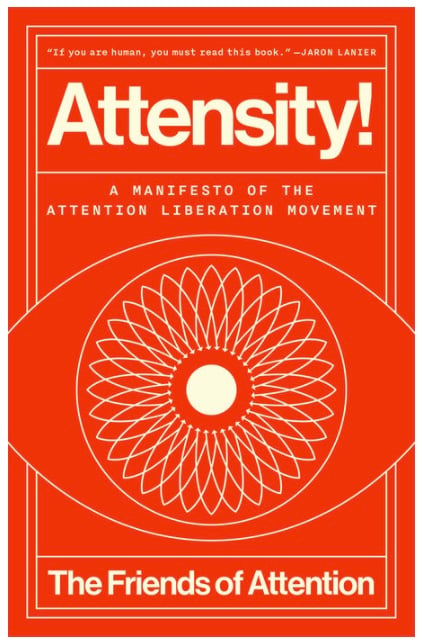

I spoke with Peter Schmidt on Techtonic this week. He’s the head of the School of Radical Attention and one of three editors of a new book by the Friends of Attention called Attensity! A Manifesto of the Attention Liberation Movement. Peter and I discussed the group’s background, and its goals for carrying out its manifesto:

Starting off the book is the manifesto itself, which calls for “attention activists” to resist “human fracking” – that is, the destruction and monetization of our attention by the Big Tech giants. And anyone can be an attention activist. I asked Peter what people should do, and he gave this response:

Get together. Get together, get together, get together. Bring your people together, and talk about your attention.

And do the stuff that you already like to do, stuff that still sits beyond the reach of these corporations. . . . A book club, or a knitting group, or a monthly dinner party. Or a hike that people take in the woods together.

Take these things and keep doing them. But recognize that somewhere out there is a business school graduate with a tie and a blazer and a PowerPoint deck that he’s presenting to a bunch of VC investors that says, this thing you love doing can be turned into an app and made into an extractive business model that will get him rich.

Here Peter touched on a key insight about our tech-dominated society. There is no sanctuary, no hiding place that is safe from Silicon Valley’s predations. Any community activity – a potluck dinner club, even a knitting circle – can be targeted by a bro to be monetized. All is vulnerable to the growth-at-any-cost mindset.

And this is why vigilance is so important. Pay attention, the book is saying, pay attention to what your community does, and what it values. “The task before us,” the authors write, “is to make ourselves fully non-commodifiable in our attentional lives.” This isn’t a call for some sort of purity of intent (no one is pure) but rather a commitment to things that matter – like community, and creativity, and mutual support – in opposition to the bros’ mindless grasping for money and power.

The source of our problems is the concentration of power in a very few hands, and those guys’ cancerous dreams of eternal growth. Their will is enacted through predatory technology – though, it must be said, technology per se is not the problem. Better technology, in fact, will help us get through this (and I’m working on Good Reports to spotlight the better options out there). But in the meantime, it’s a good idea to say “no” to most of the tech on offer. Join a community or pick up a book instead.

By the way, for anyone who wants to dive all the way into attention: Marcel Proust’s In Search of Lost Time (starting with Swann’s Way) is akin to a literary version of that MoMA film I described above. Proust’s powers of attention were phenomenal. This probably deserves its own essay, but I can say that reading Proust – which took about two years – showed me what human perception is capable of. The book isn’t always easy reading, but the beauty is breathtaking.

I’ll finish with another invitation to join Creative Good, since you are reading this on a free subscription. My writing is supported by a community of people seeking better awareness about tech – and alternatives. Members get access to our Creative Good Forum, where recent posts cover several tool recommendations for podcast apps, an ethical TikTok alternative, and better notes apps – as well as news about Big Tech’s predation on minors, a short history of the web, and another couple of additions to our good experience games list. Really, you should join us.

Until next time,

-mark

Mark Hurst, founder, Creative Good

Email: mark@creativegood.com

Podcast/radio show: techtonic.fm

Follow me on Bluesky or Mastodon