On resisting AI intrusions

For several years I’ve been following Paul Salopek, a National Geographic explorer, on his Out of Eden Walk around the world. Paul has been on Techtonic a couple of times (1, 2). One theme of our conversations has been the enduring value of indigenous wisdom and insight, especially around land management. Paul has encountered farmers, in southwestern China and elsewhere, who know how to grow crops sustainably in harsh conditions: exactly the knowledge that we’re going to need in the coming decades of climate change.

The problem is that the modern, tech-enabled world is draining our ability to gain or make use of that knowledge. For all the ways digital tech can help us communicate, calculate, and synchronize, we’re not making much effort to simply listen and learn from indigenous sources.

As I wrote in a column a couple of years ago:

Considering Indigenous perspectives is not some sort of “nice-to-have” option. If we want to find a healthier path forward, some alternative to the tech billionaires’ self-serving projects, we need to open the conversation much further than we have to date. Western science and Indigenous wisdom: we need both.

I was interested this week to see a new short film, Butterflies, touch on this idea. The video, made by an ed-tech startup developing AI-for-education products, presents an imaginary future showing how an indigenous community – Lakota, in this case – might achieve a kind of utopia through the use of AI-enabled surveillance glasses.

Audrey Watters, who has written for years about the failed promises of ed tech, posted an essay (Apr 21, 2025) about the Butterflies video:

The subtitle informs us this is the Pine Ridge Indian Reservation. It does not tell us that around 60% of the homes there still today have no electricity or water or sewage systems. It does not tell us this reservation, located in southern South Dakota, is by many accounts the poorest place in America, where the life expectancy of men like the boy in this story is a mere 48 years. . . . The fuzzy figures in the opening image aside, there are no elders, no teachers.

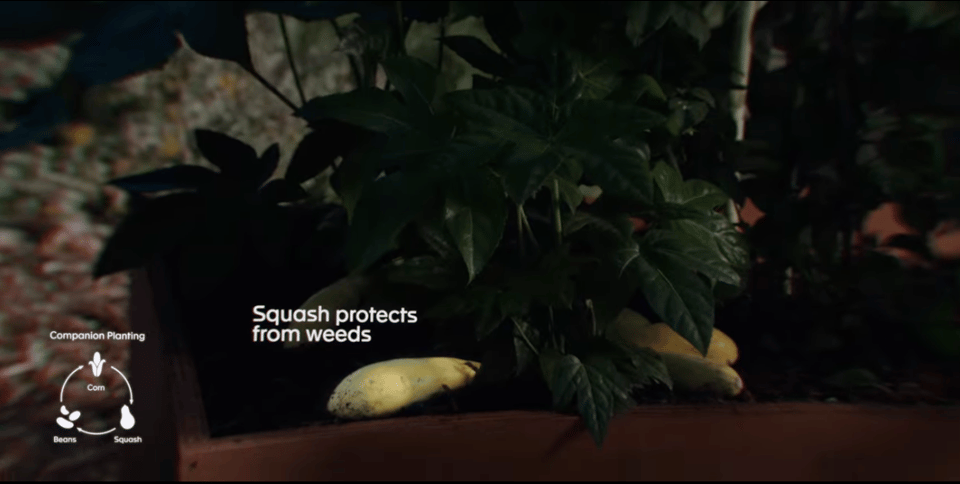

The only appearance of an elder, as far as I can tell, is about a minute into the video – and only in audio. A child is wearing a pair of high-tech AR surveillance glasses while an elder, off-screen, talks about the “three sisters” – beans, squash, and corn – which have been planted together for thousands of years.

But the child is only paying partial attention. The glasses display, shown from the child’s perspective, superimposes text (“Squash protects from weeds”) over a real-life squash. See? The kid could listen to the elder drone on about the three sisters, but how much cooler would it be to float the information on an augmented-reality dashboard:

I know this is all just notional, for how a product – if indeed it’s ever built – might possibly look. But the basic idea seems pretty obvious: the tech, made by the startup, will lead the education of the kids. Not the elders.

As if to underline the point, elsewhere in the video we see the child sitting alone at home. The device reminds the child that it’s time for bed. There’s no sign of a parent, guardian, or other caregiver. In this moment, the child is fully isolated, susceptible only to the device’s suggestions.

This is nothing new. Tech companies have worked for years to insert themselves in the middle of normal human relationships. Between parents and kids, teachers and kids, friends and friends, governments and citizens – tech companies want to sit in the middle of these, acting as gatekeeper, monetizer, and manipulator.

The idea that indigenous knowledge somehow is going to be passed down not by elders but by an app (produced by cubicle-dwelling coders) is more than ridiculous. It’s actively dangerous. I’ll say again: we need to listen to, and learn from, indigenous wisdom. Routing around the elders to deliver instruction on surveillance glasses is just the kind of idea that got us into this dystopia in the first place.

What is learning? What is teaching? Can technology help us, meaningfully, in these activities? These are some of the questions engaged by John Warner’s new book More Than Words: How to Think About Writing in the Age of AI. I spoke with Warner on Techtonic recently:

Listen to the show (interview starts at 3:22)

Throughout the book, Warner writes about the duty we have to think, especially if we have any desire to actually read or write. AI, while it can be helpful in some cases, can’t do the thinking for us – and if we want to write, or teach students how to write, we need to resist the algorithm. As Warner puts it:

Avoiding the influence of the algorithm requires a conscious effort of resistance. Getting a book recommendation from your local bookseller or librarian or friend is a small act of resisting the algorithm.

So here’s my book recommendation: More Than Words. If you listen to the interview, you’ll hear Warner give two other book recommendations for me, based on my recent reads. Take a listen.

There is a better world available to us, and it can and should include digital technology. But the tech has to be a tool, a helpmate, available to humans when we want it, and not intruding otherwise. And there’s plenty that technology could do for the Lakota, just as it could do for all of us. But talking over the elders is the wrong way to go about it.

Another act of resistance I’d suggest is joining Creative Good, our community of people exploring how tech is affecting all of us, and what we can do about it.

Until next time,

-mark

Mark Hurst, founder, Creative Good

Email: mark@creativegood.com

Podcast/radio show: techtonic.fm

Follow me on Bluesky or Mastodon

P.S. You’re on an unpaid subscription. Please upgrade your subscription to show your support.