I read all of Plato. Here's what I learned.

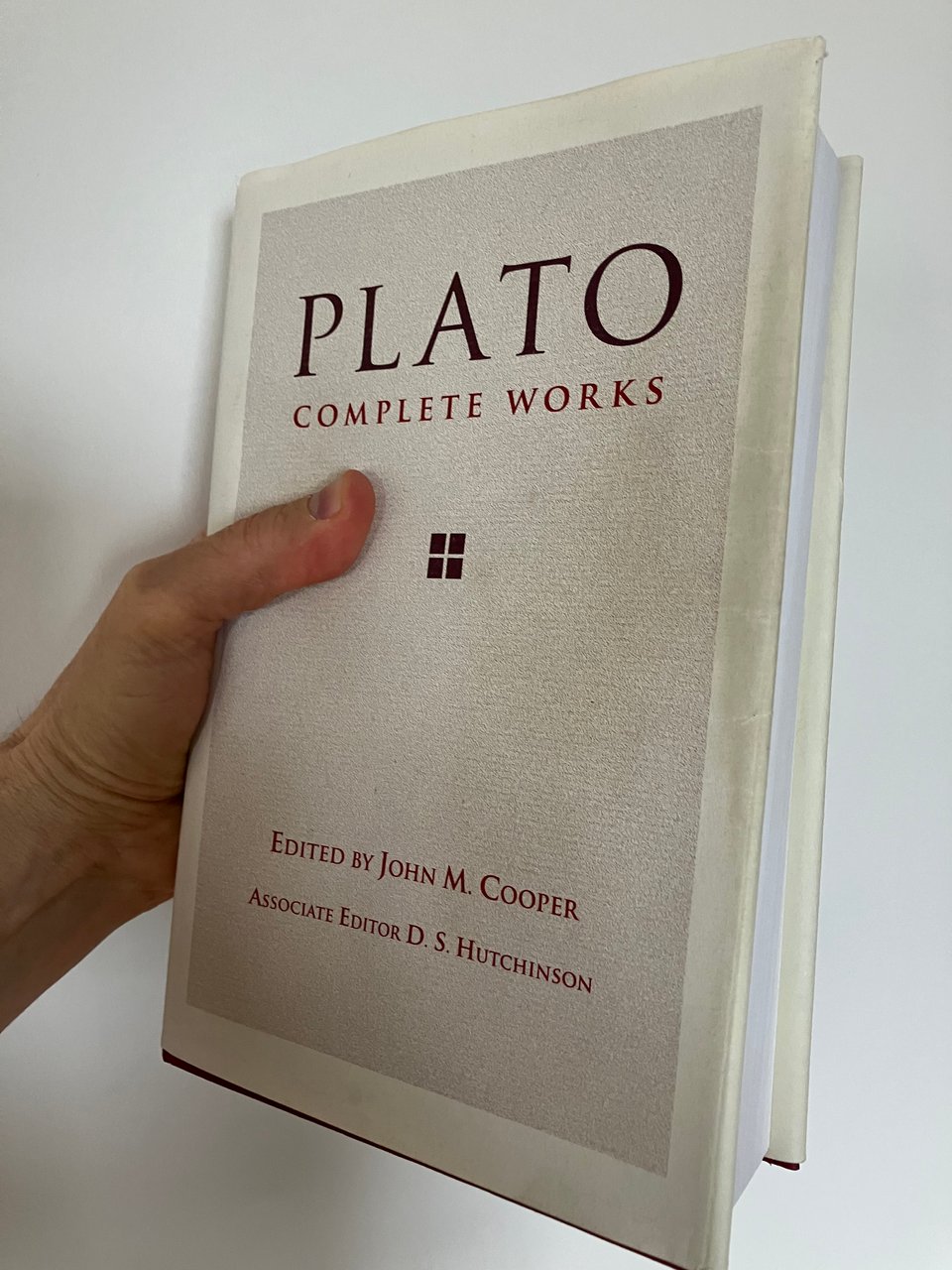

I recently finished reading all of Plato. This was Plato: The Complete Works, published by Hackett, a hardcover tome 1,775 pages long. Acting on a new year’s resolution last year, I started by reading a few pages on January 1st, then a few more on January 2nd, and kept going throughout the year, reading on average five or six pages a day, missing just a few days along the way. I finished the book in early November.

It’s impossible to summarize the book and its 40 or so dialogues. Plato’s complete works are sort of like the Bible: a collection of texts written in lots of different styles, at different times, and by different authors: while many of the works were written by Plato, several were likely written by students or contemporaries. (They’re included in the “complete works of Plato” by tradition.) This collection, then, is less of a book than a portable library.

While the works defy summarization, there are certainly high points. For starters, there are Plato’s “greatest hits” – the concepts and phrases that people today are typically familiar with. The idea of virtues, for example, and Platonic forms, and Socrates’ injunction to “know thyself” (quoting the oracle of Delphi) – all of these recur in several dialogues.

Socrates

Socrates is a near-constant presence throughout the works. In fact, the first four dialogues – Euthyphro, Apology, Crito, and Phaedo – tell the story of Socrates’ trial and execution. (Socrates drinking hemlock is another image that is still familiar today.) Most of the subsequent dialogues feature Socrates, too. Yet Plato never once appears or is mentioned in the works.

With such an emphasis on Socrates’ life and philosophy, one might wonder if it would more accurately be titled “the complete works of Socrates.” But it really is Plato’s work throughout. Socrates was Plato’s teacher, and some years after Socrates’ trial and execution, Plato founded his academy to teach Socratic philosophy to a new generation of students – one of whom, Aristotle, went on to do some writing of his own. Plato’s writings, featuring Socrates as a character, are the best glimpse we have of who Socrates was and how he approached philosophy, especially since he didn’t write anything himself. (In Phaedrus, Plato portrays Socrates as being skeptical of writing because it risked dumbing down philosophy. Live, in-person debate was superior.) It’s only through the writing of Plato and other authors, like Xenophon, that we know anything at all about Socrates.

It’s important to keep in mind that the dialogues aren’t a historical record of what Socrates did or said. Instead, each dialogue is akin to a play, written by the playwright Plato, with Socrates as a central character. The dialogues present Plato’s own philosophy, influenced by Socrates. In fact, as former Oxford professor C.C.W. Taylor writes in his Very Short Introduction to Socrates, it appears that Plato’s earlier dialogues present Socrates closer to his real-life words and behavior, while the later dialogues employ Socrates more as an avatar of Plato’s own philosophical thoughts.

The cave

Perhaps my favorite passage in the works is Plato’s cave, which appears in Republic (one of the longest dialogues, usually published as a standalone book). Before reading it, I was already familiar with the premise: a group of people are sitting in a cave, lit only by firelight, watching the motions of shadow puppets on the wall. The allegory is Plato’s way of explaining his idea of Forms: there’s an ultimate reality of existence that we, as the cave dwellers, can’t access. All we can see are shadows.

What I didn’t realize is that the allegory doesn’t end there. Plato goes on to suppose: what if one of the cave dwellers was pulled out of the cave and brought up to the surface, into the sunlight, where he could see things as they really look? The person would be resisting and complaining the whole way. Blinking in the bright sunlight, he’d say, “Why did you bring me up here? I was comfortable where I was! And now I can’t see anything at all!” Only until his eyes adjusted would he finally see the truth.

Plato then imagines what would happen if the person returned to the cave. He would of course try to explain to the cave dwellers what he had seen on the surface. They would reject what they were hearing, perhaps even violently. This is, of course, precisely what had happened to Socrates – and has continued to happen to truth-tellers throughout history.

The daimon

Another surprising aspect of Plato was his depiction of Socrates as a god-fearing believer. I had expected Socrates to embody the hyper-rationalist philosopher – and he does to some extent, as he is described walking around Athens in simple garb, often without shoes, always talking, questioning, engaging people in conversation, trying to get at the truth of the matter.

Yet Socrates doesn’t rely solely on rationality. Both in his trial and in other dialogues he states that he is under the guidance of a supernatural spirit – a “daimon” – that prevents him from straying from the path of justice and truth. In different places Socrates talks freely about his daimon, God (“the god,” in Socrates’ words), and the afterlife. For all his praise of the rational mind, in other words, Socrates can be quite spiritual. No wonder St. Augustine later declared Socrates to be the Greek philosopher closest to Christianity. (On the other hand, Tertullian wrote that Socrates’ daimon was a sign of his demonic alignment. You can’t please everyone.)

Dissonance

While Socrates’ quest for truth still resonates, there are also some aspects to the dialogues that are dissonant with society today. For example, romantic love: in Symposium and elsewhere it’s described in terms of the relations between older men and adolescent boys. Women are only occasionally mentioned in Plato’s dialogues, and never in the context of romantic love – indeed women often are disparaged, though in Republic they’re invited to take part in government and military affairs as equals to men. Another (supposedly) important idea today, democracy, is at best faintly praised, as Plato suggests that an enlightened dictatorship would be a better form of government.

Although Plato hits some discordant notes, that’s hardly a reason to abandon the dialogues. Try to find any text two thousand years old that satisfies every expectation of today’s most sensitive readers! What’s more, we can’t always be certain of Plato’s actual opinions. As scholars have pointed out, some of the ideas presented in the dialogues are meant to provoke debate. Plato is not instructing us as much as he is trying to get us to think.

Beyond illusions

More specifically, Plato invites us to think about what’s important. There is a certain question underlying most of the dialogues: what is good? Or true or beautiful or just? On the point of justice, one of my favorite scenes is Socrates asking a friend: is it better to commit injustice, or to suffer injustice? The friend responds, “to commit injustice, of course, because who wants to be mistreated?” At which point Socrates calmly and methodically shows why it’s always better to suffer than to make someone else suffer. All of this is consonant with Socrates’ many warnings against gaining too much wealth, and against being “like the sophists” in arguing what you don’t believe in, in order to gain popularity or power.

As I made my way through Plato, one thought kept coming to mind: lose your illusions. Life presents us with so many ways to hide, or take comfort, or numb ourselves with something less than the truth, less than reality. Plato is constantly challenging us to look more closely: what is really going on? What does it mean? What is the good, or the truth, that we’re striving for?

Questions that resonated in Athens in the 4th century BCE are just as relevant today. Plato offers us a vast world of ideas, poetry, stories, geometry, science, and debate to explore. And Socrates, our faithful guide, is present in most of the dialogues. It’s well worth your time to spend a year or so to make the journey.

As for me, I’ve moved on to the Iliad and Odyssey. I consider them recommended by Socrates himself: after all, Plato has him constantly quoting Homer, much like scholars today might quote Shakespeare or the Bible. Once I’ve spent some time with the Trojan War and its aftermath, I may report back.

If this column resonates with you, I hope you’ll help support my work by joining Creative Good.

Other recent essays:

Until next time,

-mark

Mark Hurst, founder, Creative Good

Email: mark@creativegood.com

Podcast/radio show: techtonic.fm

Follow me on Bluesky or Mastodon

P.S. If you find these newsletters valuable, I’d like to ask for your support. You’re on an unpaid subscription. Please join us at Creative Good. (You’ll also get access to our members-only Forum.)