A time to listen to customers

You have to wonder who approved the "anesthesia timer." As Futurism writes (Dec 5, 2024):

One of the country’s largest health insurance companies, Anthem Blue Cross Blue Shield, announced that it would no longer cover anesthesia care during surgery procedures if they pass an arbitrary time limit — only to partially reverse the policy after an enraged outcry.

When basic necessities like anesthesia during surgery are being threatened by cost-cutting, it's hard to believe that a company cares at all about patients.

Yesterday's shocking violence in midtown Manhattan has many people talking about how health insurers serve (or exploit) their patients. But this was in the news well before the assassination of United Healthcare's CEO. A year ago, for example, ArsTechnica published a thorough analysis of UHC's AI model, called nH Predict, that was used to deny claims from patients. According to a lawsuit, the AI had a 90% error rate.

It may sound obvious, or a little old-fashioned, but I have to say it: It's a losing strategy to ignore your customers. Sure, you can juice the quarterly earnings by training an AI to deny 90% of legitimate patient claims. Maybe you can squeeze out a little more margin with the "disruptive innovation" of an anesthesia timer. Each new exploitation of patients and their families gets you a bit more growth . . . at which point the market says, "Not enough. Grow more." Customers, on the other hand, can only be exploited for so long before they leave, or sue.

This raises the question: why not listen to customers and deliver what's good for them, thereby building a healthy long-term business? It's a real question. I wrote Customers Included to persuade teams to try this approach, and a few did. But not nearly enough.

Listening to customers was a theme of this week's Techtonic as I interviewed Nicole Kobie about her new book The Long History of the Future. (See episode page, listen to the entire show, jump to the interview, or download the podcast.)

Kobie's book covers several technologies that, at one time or another, represented "the future": driverless cars, artificial intelligence, robots, augmented and virtual reality, cyborgs, flying cars, hyperloops, and smart cities. In many cases, despite early hype, all that emerged were disappointing prototypes. In a few cases there was hardly anything built at all. (Remember when Elon Musk promised to create a hyperloop between Los Angeles and San Francisco?)

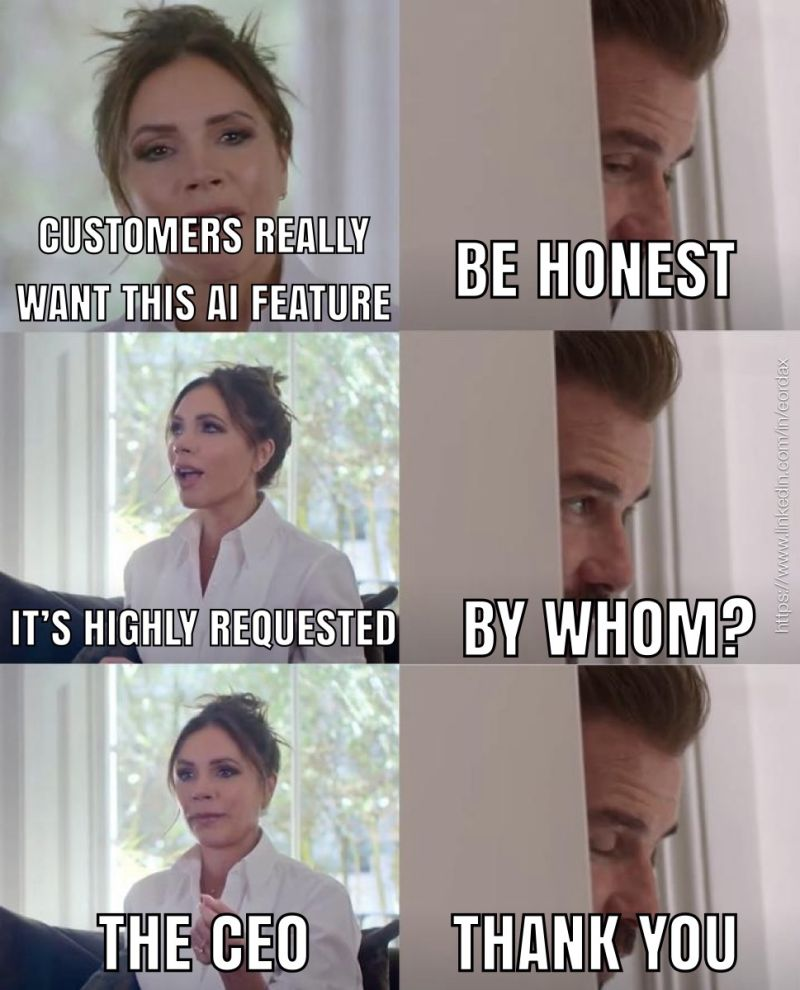

Why did so many of these ideas fail? Kobie's case studies repeatedly show inventors and product teams following their own vision of the future without spending a moment with the people the tech was intended to impact.

Please upgrade your subscription: Join Creative Good.

A good example is the chapter on smart cities, my favorite in the book. A pattern emerges: Powerful organizations like Google's Sidewalk Labs try to build a new urban environment with a strictly top-down approach. First they persuade the local authorities to hand over their cash and land, then they announce the tech to be installed, mostly surveillance and control platforms that will maximize the benefit to Google (or whoever the builder is). Citizens – the people who will have to live with all of these decisions – are left out of the process entirely. (I wrote about Google's failed surveillance city in this column last year.)

The failure of top-down smart cities came to mind this week as I read Chris Arnade's post about how to plan urban walking trips (Dec 5, 2024). Arnade writes in one passage about the classic book Seeing Like a State:

What struck me most while reading Seeing like a State was how much I agreed with the chapters on urban planning, which claim cities are more functional, at a human level, when designed via metis, from the bottom up, rather than via techne from the top down. . . .

Cities better serve the residents when there isn’t a master plan or smothering regulation, but rather where the growth is allowed to be ad-hoc . . .

Cities serve the residents better when designed bottom-up: this means understanding citizens' needs first before building solutions. Compare that to the top-down, inventor-first, "disruptive innovation" of Silicon Valley and the failed technologies in Nicole Kobie's book.

Bottom-up means listening to the users, having empathy, practicing some measure of humility, and being open to some idea other than your own being the right one to develop. In other words, the opposite of how Silicon Valley tends to work.

The tech industry has had enough time to try the arrogant, top-down, user-hostile approach. While it has enriched a few, the larger story is one of failure, and harm, and growing resentment from users, citizens, and patients.

Why not try something different? For those teams ready to build a long-term success, the "customers included" approach is still relevant, still available. (I can help, too.)

It's time to listen to customers.

On the Creative Good Forum

Our members-only Forum contains articles and discussions, organized by topic. I hope you'll join Creative Good to participate in the Forum.

Here are recent posts I'd recommend:

- Surveillance and the United Health shooter

- Photos of very dorky AR surveillance glasses from Snap (and Zuck)

- Dark patterns and ChatGPT, and Amazon Prime

- More threats from AI, countered by one tech booster saying AI is God

- Yet another creepy AI-generated short movie, in our thread of AI-generated videos

- The moon's orbit featured in our "good explainers" thread

Please join us to get access to the Forum and support my work on the newsletter.

Until next time,

-mark

Mark Hurst, founder, Creative Good

Email: mark@creativegood.com

Podcast/radio show: techtonic.fm

Follow me on Bluesky or Mastodon

P.S. Your subscription is unpaid. Please upgrade by joining Creative Good. (You’ll also get access to our members-only Forum.) Thanks!