The Seeds of Death

“The space race is over. It's been and it's gone, and I'll never get to the moon. Because the space race is over - and I can't help but feel we've all grown up too soon.”

It’s March 1988 and my friend Jonathan has a copy of Doctor Who Magazine #135. It’s a publication that I did not, until moments before I acquired the previous issue, #134, in a WH Smiths in a small town in Worcestershire, even know existed. I don’t think he did either. But a week or maybe a fortnight later, there’s a new issue, and he’s bought it. Which means I don’t have to. Because I can read his. It’s from this magazine, that I learn that a new video of an old Doctor Who story is being released at some point soon. My birthday is in very late January, and so I decide that this this will be what I spend the money that’s come in cards from various relatives on. My own brand new videotape of a new old Doctor Who I’ve never seen to keep forever and ever. I will have my own copy of Spearhead from Space!

Yeah, as you can probably tell from the story referenced in the title of this article, it didn’t quite turn out like that. From the vantage point of 2024 I know that the Spearhead from Space video came out in February 1988. So when I went looking for it in the same W H Smith that had furnished me with that DWM in mid March, they’d probably sold out of the one or two copies of the tape they’d got in for the week it went on sale, and that a backlist copy was probably on its way. At the time in 1987, I was annoyed. There was a new tape! It said so in my comic! So quite frankly why did they not have it? It was, if nothing else, great preparation for life as a Doctor Who fan, pining for episodes that no longer exist.

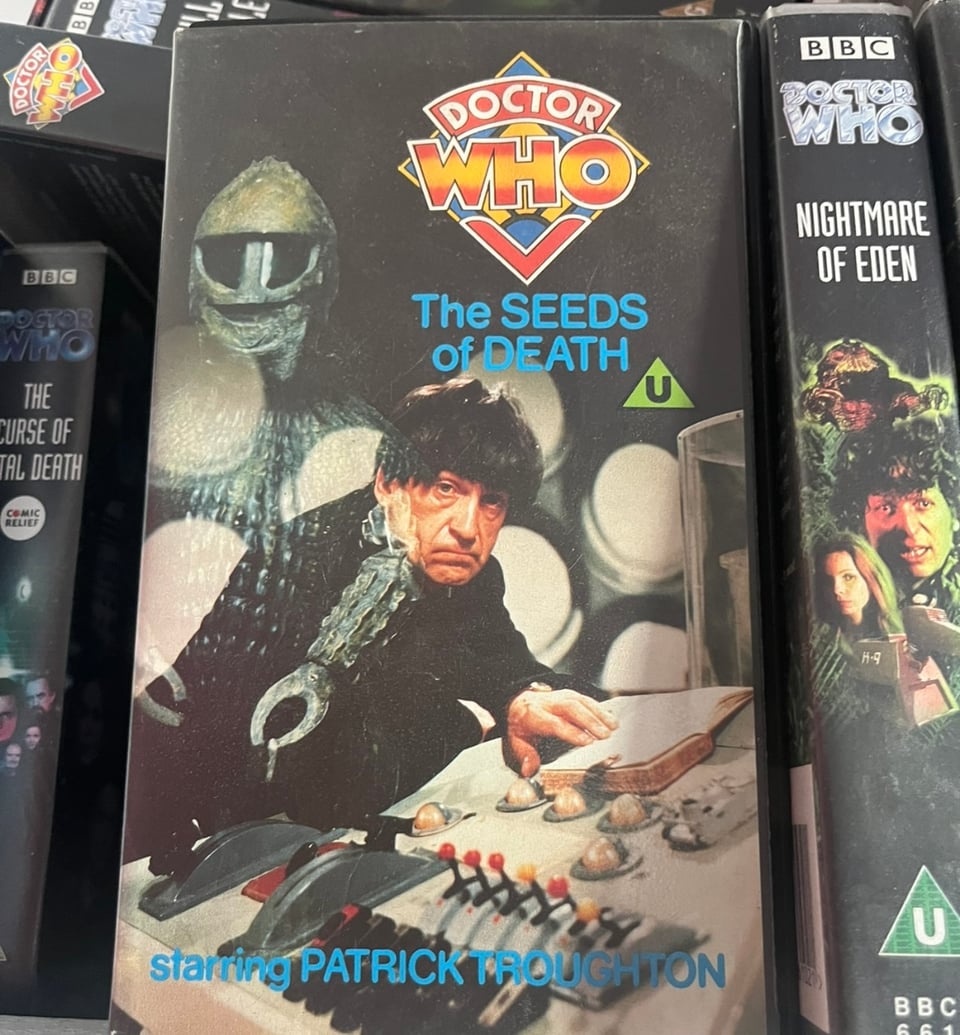

Instead we got, you guessed it, The Seeds of Death. Mostly because it was the only one of the three “Doctor Who videos” on the shelves of that WH Smith that I hadn’t already borrowed, watched and surreptitiously copied for my own further, private use.

Was I sure that I really wanted a black and white one? My Dad seemed uncertain that I could be. I was. It was partially that I knew this Doctor and his companions Jamie and Zoe (although Zoe only a little) from The Five Doctors and The Two Doctors, and that those stories are, in early 1988, fading memories. But mostly because I’d got myself to the point where I was going to see some Doctor Who I’d not seen before that day, and there really was no backing down now. (I’m much the same when the series goes out to this day, and I ain’t even lying.)

My Mom seemed pleased with my choice. I don’t know if it was before or after this that she told me that Patrick Troughton was her favourite Doctor, and that she remembered his first episode being shown when she was at school. Good as her word, she was very happy to watch it with me later that Saturday night, although she was slightly confused by how it was cut into a single long “film”, and by just how long that “film” was. We’d both misread the running time on the back of the box, parsing 136m as meaning 1hour and 36minutes. In celebration of that momentary confusion, here’s a link to Pip Madeley’s impossibly brilliant video illustrating the cuts made to the serial for this edition, which also has the advantage of giving you a sense of its vibes.

As with all these 1980s VHSes, it’s very hard for me to separate the first time I watched the stories on them from the many times I’ve seen them since, both in the immediate aftermath of that first viewing and in subsequent decades of my fandom. But whenever you watch The Seeds of Death, it takes ages for Doctor Who, Jamie and Zoe to appear. Which was rather frustrating, given that they were part of why I wanted to see it. I now know that this is the case because the production team were trying quite hard to not overwork their regular cast any more than they already were.

When they finally do appear, however, they’re instantly perfect. An immaculately balanced team. There’s an incredible ease to them, both the actors and their characters. As regular casts go, I don’t think Doctor Who has ever quite surpassed Troughton, Hines and Padbury. Equalled? Yes. But surpassed? No.

And I don’t know when I made the decision, or even if I made it at all, but Troughton, Jamie and Zoe feel “mine” in the same way the McCoy Doctor and Ace do. This is the thing about growing up in a time, which is most times after 1988, in which multiple eras of Doctor Who are at least partially accessible to the part of the audience that wants to dive into the series’ past; and so your “home era” might end up not being your own at all.

Decades later I discover that Padbury went to the same senior school that I did. A school that, at the time I was watching The Seeds of Death, I hadn’t yet attended, but for which I was anticipating having to sit the exam to see if they’d let me in.

If I’d known this at any point during the seven years I was there, I’d have looked for her in the “whole school photographs” on the wall in “the blue corridor” where she presumably crossed over with Sarah Douglas (Superman II), and where you can now find a picture containing me, Olympic Hurdler Andrew Pozzi and Numberblocks creator Oli Hyatt. Which is not bad for a state school in a town so small you could walk it end to end without noticing.

You’ll forgive this swerve into something close to nostalgia, I hope. It’s appropriate, I think, because nostalgia is something that The Seeds of Death itself is intimately concerned with, and that’s something which goes a little too unremarked upon for my liking.

The story proposes, indeed it dramatises, a future in which the shiny present of the Apollo programme, at the time of the story’s production unfolding on the television news and seemingly one of the building blocks of the future the children of the 1960s expected to live in, would be over. Finished. Kaput.

The Seeds of Death posits nostalgia for a time that, when it was written, is yet to come. Which is a good joke, and very Doctor Who. It shows, in effect, a world in which something akin to the Beeching Axe has fallen across the world of rocketry. Where an old man called “Professor” Daniel Eldred has a rocket in his back garden, in his private museum like, well, like Peter Hendy, appointed Transport Minister the day I’m typing this, has not one but two Routemaster double decker buses of his very own.

In this future, in which rockets vastly more sophisticated than the one that would soon take Neil Armstrong, Buzz Aldrin and Michael Collins to the Moon, are the preserve of hobbyists and cranks, all travel on Earth and to the Moon is conducted by “T-Mat”. Which is essentially “when you go all wibbly and disappear like on Star Trek” to quote Hugh Laurie talking in something else entirely. The efficiency of T-Mat has meant that humans as a whole are simply no longer interested in space travel, to the point where getting “beyond the moon” is not considered desirable.

This isn’t a problem, as such, until T-Mat breaks down, and it’s decided that someone from Earth will have to go the Moon and fix what is assumed to be a technical fault, but is actually the result of an invasion of the Moonbase by Martian Ice Warriors. Suddenly it’s decided that Eldred’s hobbyist nonsense might be of use to the state after all. The way this unfolds is not nostalgic exactly, not in the way Eldred himself is, but it does serve to remind us that everyone old was once young, that everything old was once new and exciting. It suggests that you should perhaps be careful what you throw away, as you never know when it might come in useful.

The Seeds of Death is also oddly accurate in its prediction. We don’t have T-Mat, of course. We’ve not yet been invaded by martians and indeed the moonbase seen in this story, implicitly the same one from The Moonbase (2070) and in 1969 something every school child expected to be built within their own lifetime, never happened. But once Apollo 11 landed on the moon less than four months after the Doctor, Jamie and Zoe did in Eldred’s rocket ZA685, the space race was effectively over. Funding and interest dried up. When Eugene Cernan climbed back into Apollo 17 and began the return journey to Earth, he became the last man on the moon until, well, some point after today. Humans have, as The Seeds of Death posited, never gone beyond the moon.

Past visions of the future can sometimes be like this; they can contain truths of an almost orthogonal kind. Another in this story is that when watched in 1988, perhaps in 1969 too, its portrayal of a world falling into famine so quickly after the incapacitation of T-Mat seemed silly: The stuff of the children’s fiction the story is. But another three decades or so on, with food supply chains snapping due to Covid or Brexit a recent memory, it’s weirdly prescient and makes total sense. Of course if you can move food around instantly you quickly evolve a society where you have to move food around instantly. We become reliant on the miraculous very easily, as a species.

If you want further proof, I have just found myself briefly annoyed that the wi-fi buffered slightly as I tried to check a line of dialogue from this story on iplayer on my phone. The whole idea of being able to watch black and white Doctor Who on a smartphone over the internet is insane, and here I am slightly miffed at a marginal inconvenience in this process. I’m more spoiled than the Earth and Moon based T-Mat bureaucrats at the opening of this story, who have no idea what’s about to hit them.

Chief amongst those bureaucrats, at least initially, is Osgood, a tubby civil servant, played by Harry Towb. A master of dialect as an actor, Towb here uses his own speaking voice, a northern Irish accent made occasionally unfamiliar by inflections resulting from the proudly Jewish Towb growing up in a multi-lingual household. Osgood’s early, brave death at the hands of the Ice Warriors makes the then well-known Towb’s turn a tiny, perfect little cameo, and surely if not quite Janet Leigh in Psycho, then the production line TV equivalent. If the same were to happen in modern Doctor Who it would be as if John Lynch were to appear at the opening of a story only for his character to be shot in the face after delivering a couple of lines.

Osgood’s death also opens the way for one of the greatest performances in all of Doctor Who, as Osgood’s protege Fewsham (Terry Scully) responds to his murder with pure, unadulterated fear. Utterly traumatised, he not only betrays the man who gave him his career, he slanders him in death as someone unable to cope with the technical emergency Fewsham pretends the invasion to be.

Scully’s compelling portrait is of someone who is not a traitor, but more a sort of collaborator, one acting out of cowardice but not conviction. The sheer moral anguish Fewsham experiences at a situation not of his making, but which he cannot summon the courage to escape, is honestly remarkable. His furtive eyes. The sweat on his face. You can feel his skin crawling as he keeps not facing up to what he’s doing.

Back on Earth, Louise Pajo’s Gia Kelly is huge fun. It would be easy for “Miss Kelly” (as she is usually called onscreen) to be a cliche. The professional woman with no emotions. But Pajo does a lot more with her, mixing character traits that might be seen to be contradictory, at least in this sort of part and at this sort of time. She’s super competent and sometimes harsh, but she’s also funny and a bit flirty, and always in control of herself and her situation. She is, in short, a character from the same mould as Zoe. If you made this story these days you’d either give them a character based rivalry or a sororal bond. Instead the barely even converse, as if the story isn’t quite sure what to do with both of them. It’s a shame, if par for the course for the era in which it was made.

In 1988 black and white television of that era seemed, inherently if not prehistoric, then certainly pre-war. There was not, in my generation of kids, a reluctance to engage with black and white material, as black and white films were still shown on television in prime time in the late 1980s, but there was a recognition that they were old. They were watched with a different mindset.

But the truth is, The Seeds of Death is a fabulous production, an incredible piece of late 1960s VT drama. Director Michael Ferguson, working in the unenviable environment of Lime Grove Studio D, a space considered unsuitably cramped and primitive for Doctor Who in 1963, achieves wonders. He places his cameras high in order to maximise shooting space; small rooms like the cupboard in which characters hide from the Ice Warriors are viewed chiefly from their own ceilings. He projects images onto actors faces to suggest they’re in a vast rocket control room, not the corner of a reused museum set, and from half way though the story he starts standing one of the non-speaking Ice Warriors against the throbbing light background in Moonbase’s main control room, creating unusual light patterns and a greater sense of space.

Ferguson was a great servant to Doctor Who, although not as great as Terrance Dicks, the serial’s script editor, and credited on the VHS cover as its co-author, although not acknowledged as such in its opening titles. His contribution is backed up by production paperwork that has Dicks redrafting the back two thirds of the story when what author Brian Hayles delivered wasn’t quite to his taste.

In later years Dicks would note that the solidly professional Hayles was never prissy about being rewritten, and happy to take the acceptance slip and move onto his next job, contrasting them with Mervyn Haisman and Henry Lincoln, who had taken permanent umbrage when he did something not a million miles away with their The Dominators (1967).

Dicks’ version of Doctor Who is not quite full formed here. It’s a little, if not bloody, then quick-to-violence as a solution in a way he would later explicitly disavow. Nevertheless, there’s something perfect about the way the Doctor tricks the Ice Warriors with a duplicate of their own homing beacon sound and when threatened with death for it calmly responds, “You tried to destroy an entire world”. It’s a moment you can imagine with any Doctor since.

A little while after we first watched this story, but surely not before I had managed to watch it again, my Mom managed to find her school news book from 7th November 1966, in which she had written that she’d watched Doctor Who the previous Saturday and that to her surprise “Doctor Who is now Patrick Troughton!” She had kept it for 22 years. She’s kept for another 37 since. Last year, I was able to quote from it as a contemporary viewer’s reaction to Troughton’s casting in an article I wrote for Doctor Who Magazine.

Be careful what you throw away. You never know when something might come in useful.