The Masque of Mandragora

“Looking for words to say. Searching but not finding understanding anywhere. We're lost in a Masquerade.”

The initial impetus for The Masque of Mandragora (1976) was aesthetic, rather than narrative. Producer Philip Hinchcliffe wanted to do a serial set on the cusp of the mediaeval / renaissance periods, and preferably in Italy.1 His Script Editor Robert Holmes wasn’t keen, regarding “historicals” as a boring subgenre Doctor Who was best off avoiding.2

As ever with Holmes, the way to his heart was through horror, and while writer Louis Marks was hired because he was the holder of an Oxford DPhil about the exact time and place that Hinchcliffe wanted the story set, what Holmes briefed him to write was a Doctor Who version of Edgar Allen Poe’s (very) short story The Masque of the Red Death (1843).3

These respective spheres of interest are, incidentally, why I’d bet you anything you like that Duke Giuliano’s brief speech about how his belief the world is a sphere is unusual, even heretical, was written by Robert Holmes. The spherical Earth was a concept understood for a thousand years by Giuliano’s time. This slandering of early modern people’s understanding of the world they walked on is a nineteenth and twentieth century historical misconception for which we can blame, amongst others, Thomas Jefferson, Washington Irving4 and George and Ira Gershwin. It’s also a mistake it is fantastically unlikely Louis Marks, author of The Development of the Institutions of Public Finance in Florence during the Last Sixty Years of the Republic, c. 1470-1530 would make.5

It’s equally unlikely that it’s a coincidence that Roger Corman’s 1964 film version of The Masque of the Red Death (which had had its UK TV premiere on 29th December 1973) was scheduled to be shown again on Monday 12th January 1976. This was six days after Marks’ scripts were commissioned6 close enough that Holmes, Hinchcliffe and Marks would all have known it was due to be on. If nothing else, the Radio Times would already have been printed. Surely they all watched along separately at home and then discussed what they wanted to take from it?

And take The Masque of Mandragora does, from both the story and the film; its human villain Count Frederico is introduced to the audience in the same manner as the film’s Prince Prospero; while he’s burning a local village for sport. This is an event found nowhere in the short story itself. Story, film and Doctor Who serial all feature a character having a mask ripped away to reveal something other than expected behind it, although here Doctor Who cleaves closer to Poe than Corman. Most importantly Mandragora, like Red Death, has a Masquerade which is actually staged; its presence in the title isn’t an affectation - its a description.

There are important differences too. Count Frederico is not, unlike Prince Prospero, a technically legitimate ruler even though he’s also a despot. He’s a wannabe usurper, and it’s Shakespeare’s Hamlet (1599) that’s the obvious source.7 Frederico is a wicked uncle looking to take the place of a noble nephew, the aforementioned Prince Giuliano, after poisoning his father. The Masque of Mandragora starts at the death of the father, something long in the past when Hamlet itself begins. The serial’s dialogue isn’t actually written in blank verse (the two step da-dum ten beats per line of much early modern drama including Hamlet) as sections of The Crusade (1965) and even Silver Nemesis (1988) are, but plenty of the actors in the story deliver it like it is, giving it a courtly rhythm that befits the serial’s settings and concerns.

But that’s just an indication of how it’s not only Hamlet but the whole genre of Renaissance tragedy (of which Hamlet is now the most famous example) that is being drawn upon. (E.g. Thomas Middleton’s The Revenger’s Tragedy (1607) features another Masque, one which as in this serial, is staged to celebrate a Duke’s ascension, and at which the appearance of a star is the signal for the Duke’s followers to be killed.) It also seems obvious that the serial’s sorcerer-astrologer villain Hieronymous owes his name, if not much else, to The Spanish Tragedy (c1592) aka Hieronimo Is Mad Again, but there are other, less obvious sources.

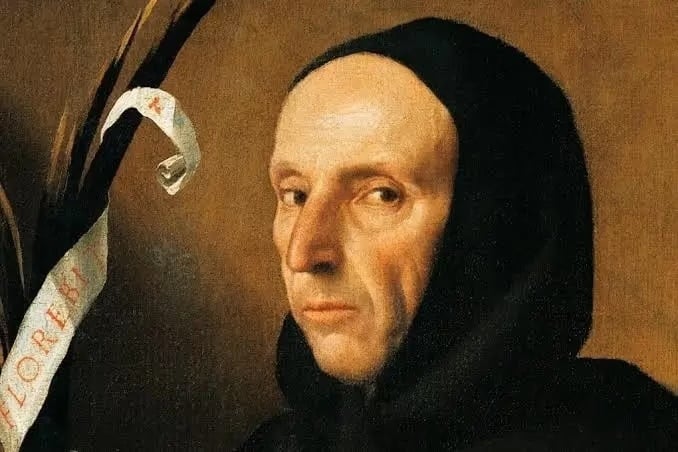

The Mandragora (1524) is a play by Nicolai Machiavelli, written in, and about, the Florence about which Louis Marks wrote his DPhil, and in the government of which Machiavelli worked. As such it’s again vanishingly unlikely that Marks would not have been aware of it. We certainly know that Marks was aware of Girolamo Savonarola (1452-1498) about whom he wrote a lengthy biographical article in History Today while a doctoral student. This Hieronymus (both names are differing translations of Jerome) was an ascetic friar who was eventually executed for heresy, and has been separately characterised as a populist, an apocalyptic prophet and a social reformer by competing historiographies. Surviving portraits of him may well have influenced the casting of Norman Jones in this Doctor Who serial.

What is important about Doctor Who’s Hieronymus, whatever his influences, is that the wicked Count Frederico has no more respect for his astrological practices than Prince Giuliano does. This is not a battle between “superstition” and a “new learning”, even though it’s the “old learning” that the Mandragora Helix intends to hollow out and use to rule humanity and beyond. This is a battle about what form the change that is going to come, regarded whiggishly as inevitable, is going to take. A “renaissance” as late twentieth century Oxford and Cambridge men like Marks and Hinchcliffe would characterise it, or an altogether grander kind of rebirth, as a phoney astrologer takes mankind out to colonise not just the “new world” as Columbus would, but the stars themselves.

His thinking and terminology in interviews reflects, as you’d expect for a man of his generation / education, the seminal The Civilisation of the Renaissance in Italy (1860), which remains a set text into the present century. ↩

Which is ironic in retrospect, with him having written three of the most acclaimed, The Time Warrior (1973/4), Pyramids of Mars (1975) and The Talons of Weng-Chiang (1977). ↩

Seriously, it’s so short my brother in law has a T-shirt with the whole story printed on it, and you can read it and everything. ↩

It was Irving’s romanticised and decidedly unscholarly storybook life of Columbus that tied the colonial voyager and exploitationeer’s (failed) attempt to reach China by sailing West from Europe and (accidental) landfall on what we now call the Americas to a (non-existent) fifteenth century belief that the world was a flat disc. ↩

It will also never not be funny that immediately before this conversation they walk past a statue of Atlas holding a globe on his shoulders. ↩

6th January 1976 was the day that Hinchcliffe formally requested permission from Marks’ employer, the BBC Plays Department, to use their staff member as a freelance writer on Doctor Who. Such approvals were a formality and this indicates the scripts were going ahead. ↩

Rather than his The Tempest, from where the name “Prospero” comes. ↩