"Terror of the Vervoids" (The Trial of A Time Lord Parts 9 to 12)

"And the leaves that are green turn to brown, and they wither with the wind. And they crumble in your hand."

Seen: 1st to 22nd November 1986

The Long Way Round

Married writing team Pip and Jane Baker came to Doctor Who quite late in a long, shared career in television and film. They were brought to the series by then-producer John Nathan-Turner during planning for the 1985 series, the first to star Colin Baker in the title role.

The Mark of the Rani was a historical story, set in 1813, and featured the Doctor’s recurring nemesis the Master (Anthony Ainley) and a second Time Lord villain of their own creation, the Rani (Kate O’Mara). Both characters were interfering in human history and in each others plans to do so, with a tripartite rivalry between three character explicitly said to have been an university together emerging through the Doctor’s frantic attempts to stop them.

The Bakers' 2x45m scripts were whimsical, verbose and not particularly violent, and they delighted Colin Baker. Pip and Jane subsequently attended the extensive exterior filming for The Mark of the Rani, conducted at the Blists Hill section of the Ironbridge Museum, and the three Bakers formed a kind of mutual appreciation society at the location hotel, enjoying discussing contemporary politics (Pip and Jane had met as young Labour Party activists during the 1955 general election and were still politically active), and shared cultural interests, including the work of Charles Dickens.

Baker the actor would later quote the Writers Baker as being particularly adept at writing for his characterisation of the Doctor, while joking that his appreciation was not down to nepotism and that despite the shared surname he and Pip and Jane were not, so far as he was aware, related.

When unseasonal rain storms cut into the serial's location days, the writers impressed both their namesake actor and producer Nathan-Turner by hurriedly rewriting material for different locations while retaining all essential plot and character elements of the scenes, and by doing so without complaint. Their returning to write more Doctor Who became inevitable. Seemingly because the production team enjoyed their handling of a story involving multiple Time Lords, the Bakers were subsequently commissioned to develop a story entitled Gallifrey for the 1986 series.

This happened despite Mark's scripts not being at all to the taste of Doctor Who’s script editor, Eric Saward. (Presumably exactly because they were whimsical, verbose and not particularly violent.) Despite this, he acknowledged them as solid, and professional pieces of work and as such they (and unlike many scripts in this period) passed through his office with no substantial rewriting.

It's a curiosity of Saward's editorship that scripts tended to fall into three categories. Those written by writers he admired (Robert Holmes, Philip Martin) that were largely untouched because of that admiration. Those he was unenthused by but which could be made (such as the Bakers and arguably Terrance Dicks) which went largely untouched for the opposite reason, and those he felt required substantial reworking on tone or practical grounds which would become, in effect, co-writes (by his account these include The Awakening and The Twin Dilemma).

Saward's direct work on Mark seems to have consisted of several small cuts and the occasional clarification, most of them related to the series’ continuity. An example: expanding dialogue where the Doctor’s refuses to carry a firearm, presumably because in other stories in which Saward was more heavily involved, he had done so, and with no notable reluctance, and the incongruity required explanation.

A fortnight after The Mark of the Rani completed transmission, this happened. Nathan-Turner and Saward, their programme embattled and both of them unsure of what creative direction to pursue, eventually began planning a new 1986 series. Initially the Bakers were encouraged to redevelop Gallifrey in the 4x25m format the series would be reverting to when it returned, but eventually the story was dropped. In part, it seems, because Saward did not share Nathan-Turner’s enthusiasm for the writers, and the series' screen time was being, more or less, halved. So, Doctor Who and Pip and Jane Baker parted ways.

The next February, Pip and Jane stepped out of a lift at BBC Television Centre and almost directly into Nathan-Turner, who was trying to enter it in both a hurry and a cloud of cigarette smoke. "Where on Earth have you been?" he asked, slightly more than rhetorically, "We need a story!" Perhaps taking the question rather too literally, Jane replied that they had been on holiday in Spain visiting family for the best part of a month. The producer explained that the 1986 series of Doctor Who had a four part hole in its schedule, with production already under way. Were they available?

Despite Saward's best efforts four of the final six episodes of The Trial of a Time Lord were still unassigned. (The last two had been earmarked for Robert Holmes, Saward's favourite Doctor Who writer, for more than a year.) Saward had initially commissioned two two-part stories from David Halliwell (Attack from the Mind) and Jack Trevor Story, and when they were written off, a four part one from Sapphire and Steel creator PJ Hammond. When that was written off, he had turned to another predecessor as Doctor Who's script editor Christopher H Bidmead for help. Bidmead who wrote a four part story called Pinacotheca (which is Ancient Greek for "picture gallery"). This too was then written off. (Anecdotally, Nathan-Turner liked it, but Saward didn't. No one outside the production office seems to have ever read it, but Bidmead retains a copy.) Pip and Jane were still not Saward's favourite writers, but the situation was desperate.

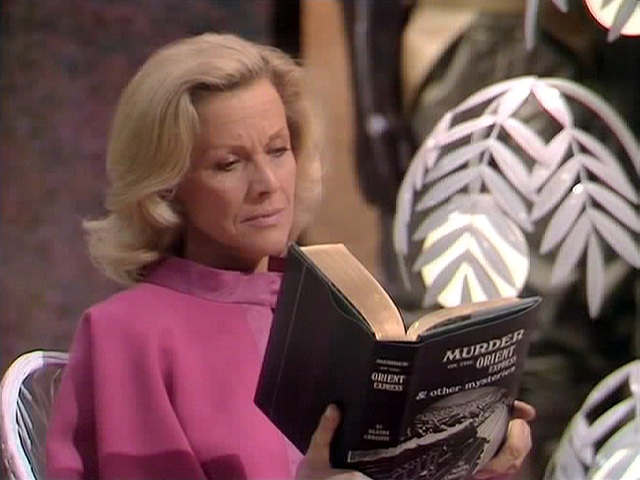

A formal meeting between the Bakers, Saward and Nathan-Turner followed soon after that impromptu lift meet. Asked if they could to provide a four part serial "in the style of Agatha Christie" and at some speed, the Bakers were also informed that, unlike The Mark of the Rani, the story would have to be shot entirely within a television studio. In practice, this meant a story that took place entirely indoors, fake exteriors created in a videotape studio on Doctor Who’s limited budget tending to look exactly that: Fake.

After brief consideration, the Bakers offered to write a murder mystery serial set on luxury space liner, which they would later christen "Hyperion III". Nathan-Turner specified that once the commission was agreed the story would need to be written at the pace of roughly an episode a week. Pip proposed that he would drive a typed draft of the first episode (Part Nine of the overall fourteen) to BBC Television Centre on an imminent Sunday. The next morning, after an initial reading, Saward could call them with either notes on how to proceed or an instruction to down tools if the scripts weren’t developing in a manner which was to the production office’s liking. With this unusual plan accepted, the scripts were formally commissioned on the 13th March.

It is very tempting to see in the request for a "Christie" story from JNT another attempt to pre-emptively deflect criticism from his departmental boss, Jonathan Powell, an enthusiast both for the writer and the then current BBC1 series of adaptations of her Miss Marple novels. (Powell was given to effusively praising them in the semi-regular meetings of staff producers Nathan-Turner attended.)

Another likely influence is the 1976 Doctor Who serial The Robots of Death. Greatly loved by fandom, it is also a murder mystery with art deco influenced design, one set entirely inside a large vehicle and recorded entirely inside a BBC videotape studio. It was also due to come out on VHS in April 1986, and Nathan-Turner would necessarily have been aware of that. (The story had already been classified by the BBFC for home exhibition when the Bakers stepped out of that lift.)

As with much about 7A it is tempting to discern in both the failure to agree on scripts, and the subsequent wholesale gestures towards two of the series' most strident critics, a production team no longer happy or confident in their own work, or sure of their own judgement. Unbeknownst to the Bakers, the producer and script editor’s relationship was severely strained, a result of creative and personality clashes that both had attempted to hide, in so far as possible, from others working on the series.

The first episode of a story which the Bakers themselves always referred to as simply "The Vervoids" was delivered and accepted via a phone call from Saward. (The now de facto title for The Trial of a Time Lord Parts 9-12 is Terror of the Vervoids; this was a title suggested by W H Allen for the novelisation, and almost certainly prompted by editor Nigel Robinson, a fan of Doctor Who who was aware of the 1970s serials Terror of the Autons and Terror of the Zygons.) After some brief discussion between Saward, Nathan-Turner and the Bakers, work began on the second episode.

Then the Bakers received an unscheduled call from Nathan-Turner, informing them that Saward had resigned from the BBC. He had been unhappy professionally for some time, but his exit had been prompted by a specific, tragic event. Robert Holmes had been hospitalised with hepatitis and his condition was deteriorating rapidly. He had been unable to recognise family or friends when Saward visited him at Stoke Mandeville, a situation that the younger man found extremely distressing.

Holmes’ unwritten script idea for the Trial's conclusion would, Saward and Nathan-Turner had agreed, be adapted and completed by Saward, in his new freelance capacity. From now on Nathan-Turner would perform "double duty" as both producer and script editor on the story, Powell having claimed in a recent crash meeting with the producer that there was no staff or contract script editor available to assist him. JNT professed himself happy with the Bakers' work. Would they continue to deliver an episode a week as arranged? They did so. Nathan-Turner duly accept them, week after week. He and his office staff ran a book on who the murderer would turn out to be, with most the money going on the innocent red herring, stewardess Janet.

Pip and Jane had, unlike the writers Saward had earlier approached to write for Trial, not been informed of much of the over-arcing plot of the series, such as the Valeyard's identity as a future, corrupted incarnation of the Doctor, or Saward and Holmes' plan to end the story on a universe-threatening cliffhanger. Whether this was because Saward perceived them as Nathan-Turner's writers rather than his own, a simple matter of time running out or just because their job was to introduce and resolve a plot of their own and loosely within The Trial of a Time Lord's format, we just don't know.

Although destined to be Parts 9 to 12 of the overall Trial story, the Bakers' whodunnit was scheduled to be largely made after the Holmes/Saward concluding two parter. To be strictly accurate, the Bakers' four and Holmes’ and Saward's one each were a single production (code: 7C). In budgetary terms they were one six part story. Not a four parter and a two parter or six fourteenths of an epic whole.

The plan was to shoot the location scenes for the final two episodes, then the courtroom scenes for all six, then the "evidence"/whodunnit scenes for 9-12. This would enable the disposal of the courtroom set and the releasing of Michael Jayston (the Valeyard) and Lynda Bellingham (the Inquisitor). Their scripts in the bag, and with no location shoots to visit, Pip and Jane Baker and Doctor Who parted company again. "We finished with The Trial of a Time Lord and were off to other things!" Pip would observe decades later on the DVD edition of the serial.

Discussion of The Trial of a Time Lord often entertains the assumption of a kind of dichotomy between Mindwarp and the four episodes that followed it. Almost to the extent that to like one is to necessarily dislike the other. They are certainly hugely different in important ways. One was always part of the Trial concept. One was an absurdly late, extemporised addition. Whereas Mindwarp requires the Trial format in order to exist, Vervoids would, it has often been argued, be better when freed from it. (Just such an edition, one removing the courtroom scenes and allowing the murder mystery on Hyperion III to stand alone, was produced for the Trial's Blu-ray release. You can judge for yourselves.)

Terror of the Vervoids is not difficult or complex like Mindwarp. It does not ask much of the audience, although if they wish they can attempt to solve the "whodunnit" aspect of the plot. What it offers, outwith the Trial, is a very straightforward kind of Doctor Who. Saward's concerns and interests vanish from the series between Parts 8 and 9 of the Trial, and suddenly we have a story which has a Doctor who presents as its central character. One who is solving mysteries and trying to save lives. He's assisted by someone whose company he plainly enjoys, and she clearly reciprocates that affection. They have adventures. The characters and the audience have fun.

This is a story in which good actors enjoy themselves portraying broad archetypes (bitter policeman, old duffer, amoral scientist, frustrated junior officer, crusty senior officer) who nevertheless have clear and coherent reasons for doing what they do. It has monsters! Murders! Spaceships! Fights! It is honestly remarkable the extent to which, out of nowhere, the Bakers' story represents Doctor Who on an even keel. For better or ill this is a Doctor Who story you can imagine being made with either Patrick Troughton or Jodie Whittaker in the lead. It's not particularly remarkable Doctor Who, but at this point, it's almost remarkable that it is Doctor Who at all.

We can also note that the story has three absolutely banging cliffhangers, and glorious moments such as when the Doctor smashes a fire alarm in order to distract attention from what he's doing. We can say how the death of the murderer Doland is a perfect example of how Doctor Who can do violence and horror without sadism in a family friendly context. We can deflect criticism of how many initially seemingly unrelated subplots the story has by pointing out that it's a pastiche of a genre where that's commonplace, and my god it's surely better than having a second or third quarter in which almost nothing happens. We can even suggest that Pip and Jane reveal a fairly acute understanding of the Doctor as a character when Laskey asks him "Are you a comedian?" and he replies "More a sort of clown, actually."

This is a story I remember vividly from transmission, and vividly remember enjoying. It's also my wife's earliest memory of Doctor Who. (She mostly remembers being scared.) Can we pick out complexities from it? Big themes? Big ideas? I don't know. We might note that the ardently left-wing Bakers supply another story where the real villain is the profit motive. We might wonder if the security officer being corrupt represents a distrust of law enforcement. (If you think that's a stretch, consider how fandom automatically categorises the communist Malcolm Hulke's portrayal of western military figures.)

At the same time, it's probably best not to look for meaning in the occasional references to the artificially created Vervoids as a potential enslaved labour force. Not least because they're wiped out by the Doctor at the end, in what has become a "kill or be killed" scenario. That's something else this story shares with The Robots of Death. It's easy, but probably unwise, to read both as stories about a slave revolt being crushed, with the stories, via the Doctor, endorsing said crushing. Which is not something which the politics or personalities of the authors of either serial could accommodate. The artificiality of the life-forms in both instances provides, if not a get out, then something to be squinted away.

It's probably best for us all to just enjoy the serial's surface pleasures, for me to say that this is a straightforward post about a straightforward story, and that we should all just enjoy the really nice scene where Professor Laskey and Mel talk about the plot over the Doctor, not permitting him to interrupt them. It's not something you can imagine happening to a male character under Saward's editorship.

Weeks later, the Bakers were attempting to watch live horse racing on television, when the phone rang. Jane answered it while Pip monitored the result of a race on which they'd bet earlier in the day. Jane was surprised to hear Nathan-Turner’s voice on the end of the telephone, and even more surprised when he bypassed social niceties and came straight to the point: There was a taxi on its way to their home, and on its back seat was a script. He would like the Bakers to read it, and then come to see him at BBC Television Centre in the morning.

Disconcerted by this, Jane initially assumed that the script was an episode of their Vervoid story, that it had been rewritten internally for some reason, and that the producer was asking for their approval of, or consent to, changes which had been made without their input. Interrupting a question related to this assumption, Nathan-Turner informed her that it was the script for The Trial of a Time Lord Part Thirteen, the episode following the end of their own story-within-the-story.

Doctor Who’s problems had been underplayed to the writers, and as they headed to Television Centre to meet Nathan-Turner the next morning, expecting a relaxed convivial meeting involving coffee and BBC gossip, they had no idea how bad the programme’s behind the scenes problems had become, or that they themselves were going to be asked to solve them.