Season 15 - Part Two

“Why take the smooth with the rough? When things run smooth, it’s already more than enough.”

This month Doctor Who The Collection Season 15 is released on Blu-ray. This isn’t a review of that box set. Not least because I did some work on it and therefore consider myself recused. Instead, this is the second part of the latest in a series about Doctor Who’s “seasons”. The first part, which is free to read, can be found here. Earlier examples of this kind of essay can be found here and here. More will follow! But not necessarily in the right order.

The fourth story of the 1977/78 season The Sun Makers was the last transmitted serial commissioned by outgoing script editor Robert Holmes. It's also one of a handful of Doctor Who serials on which no script editor is credited at all. This is not because it was made in the handover between Holmes and his successor Anthony Read. The story was ultimately scripted and produced before Image of the Fendahl, the previous story in transmission order. It was instead to avoid Holmes being double credited on its episodes. Because as well as its commissioner, Holmes was also the serial's author.

Now, there are very good practical reasons for an outgoing script editor / head writer on an ongoing series to leave behind a script for their successor that would require minimal work, and in practice it happened on old money Doctor Who more often than it didn't. But double crediting was a practice frowned on in the BBC Drama Serials department of the era, although there seems to have been more tolerance of it in Drama Series, at least for those who, like writer / producer / director (and frequently credited as all three) Terence Dudley, enjoyed a strong social relationship with the department's head, Andrew Osborn.

The Sun Makers has long been trumpeted as proof that Doctor Who can "do" politics. As such, it's source of pride for fans as a demonstration that the show is not “just” a children’s programme. That it is a story that presents oppressed worker rising against a corporation and paraphrases Marx for pun purposes have led those same fans to see it as a left wing serial. But while the story seems to have initially been developed as a kind of critique of economic colonisation, the East India Company and Company Towns and so on (something dialogue in the finished serial occasionally seems to reference) and Holmes' anti-colonial bona fides are sound (e.g. Carnival of Monsters) ultimately it ended up as something else entirely.

Holmes had, by his own account, received an unexpectedly high tax bill for the preceding financial year. Presumably as a result of him commissioning himself to write ten out of the preceding production block’s twenty six episodes. Because of this The Sun Makers is loosely constructed around criticisms of the tax policies of the then government, the James Callaghan ministry.

Frankly, there is not a left wing way for an inevitably well paid television writer to complain about his own income tax liability under a centre left government. Even if there were, perhaps by employing tropes from Robin Hood stories about elite luxury and a distant war, a Doctor Who story that literally begins by employing the common right wing rhetorical move of positioning Inheritance Tax as a cruel and immoral tax on the act of dying itself is clearly not interested in attempting one.

Inheritance Tax, at the time (and more accurately) termed Capital Transfer Tax, was as much a right wing talking point in 1977 as it is today. And I do mean literally today. On the morning I type this, the Financial Times is reporting that Chancellor Jeremy Hunt is under pressure from colleagues on the government benches to make a reduction in the IHT rate if there is another fiscal event before the next UK general election, due before the end of January 2025.

The inescapable conclusion of The Sun Makers and the known circumstances of its composition is that Holmes sees himself as a representative of those oppressed, revolting masses, and his income tax bill as the proof of his oppression. (Revolution can come from any point on the political spectrum, after all.) While it's true that in 1977 the highest rate of UK income tax was 83p in the £1.00, and many who do not themselves think they are on the political right might think this too high, this only applied on earnings over £20,000.00, a sum which is well over a £100,000.00 p/a in 2024 money.

Had Holmes' self commissioning pushed him into this bracket? Who knows. But that he was able to again commission himself for work worth, in 2024 terms, around £15,000.00 in order to pay it must surely limit any sympathy we are required to give. (Your mileage may vary. But don't forget to get a VAT receipt for your petrol either way.)

On the 2011 DVD release of this serial Louise Jameson confides in the viewer that Holmes told her the story was not really about tax at all, but about his frustrations with the BBC. This idea is found nowhere else in the paperwork or other anecdotage, and is easy to see as Holmes attempting to preemptively persuade someone firmly to his left that his story was not an attack on the government they supported. Despite its villain being deliberately styled to look like the then Chancellor of the Exchequer, Denis Healey.

(Besides, surely an attack on the BBC Holmes was leaving would, instead of lines about “corridor P45” and tax being like tribal sacrifice instead complain about various BBC ranks and acronyms, and the then problem of parking at Television Centre? The canteen on Pluto would be notoriously bad and the dictator, D-Tel, would occupy a mysterious “sixth floor.”)

The Sun Makers problem isn't that it clearly has centre right politics. Things are allowed to have centre right politics, even if I don’t. It’s that all it really has is its politics. There aren't really any monsters. Or action. Or excitement. All you're left with is a handful of semi-satirical gags. Or rather "gags". The late Barry Cryer once advanced the concept of “jokoids”, defined broadly as something that had the shape of a joke, but did not contain any actual humour. This, fundamentally, is the nature of The Sun Makers’ quips.

I mean, at least when George Harrison did it, Paul McCartney put a decent guitar solo on to distract us.

The story’s other main element is an amping up of the sadism that had begun to disfigure Holmes' work on Doctor Who, particularly in the Chancellor's, sorry, the Collector's, treatment of Leela, which is explicitly framed as having a pseudo sexual element. (In the script, this is even more obvious the Collector wishing to hear Leela's death agonies in "duosexophonic sound".) It was time for a change.

The Sun Makers’ director Pennant Roberts had a knack for casting, and was beloved of many fine actors, including Louise Jameson, but there are times in his television career when it seems like he doesn't know one end of a television camera from the other. The Sun Makers is certainly one of those times. There are boom mics visible, shooting off off set and then cameras crashing into the scenery, and those are from the same brief scene in Part Three. The Sun Makers is genuinely badly made television in a way that Doctor Who often is in cliche, but rarely is on actually viewing it - and it is the second story this season to be so after The Invisible Enemy.

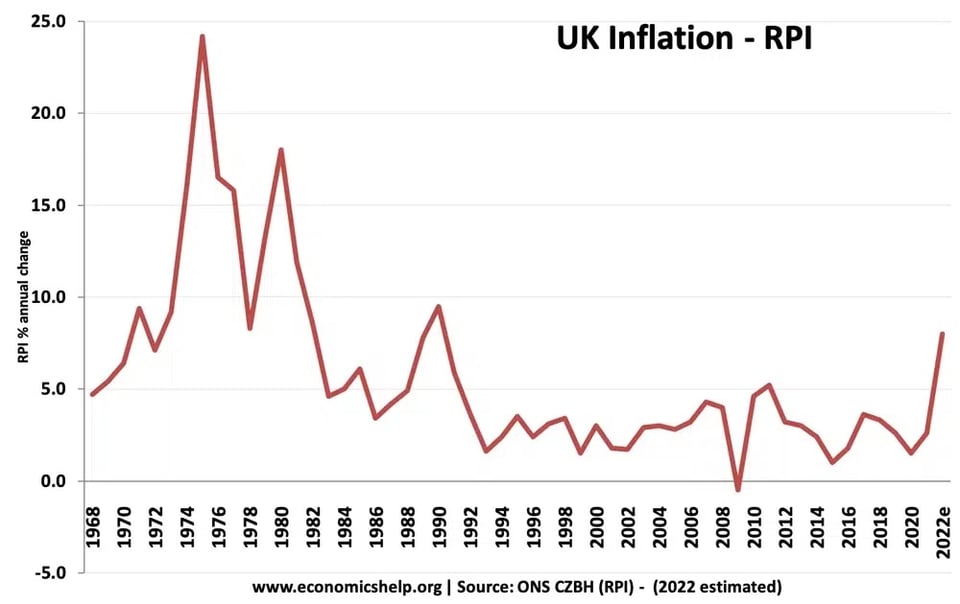

When queried about production standards in this era, producer Graham Williams, who had come on board Doctor Who with the aforementioned Enemy, would usually cite the 1970s inflation shock, on one occasion claiming, to fanzine dwb that ".. inflation was running anyway at 25%, so you're faced with making the programme for something like 30 less!"

Now, that's just not true. Not merely because inflation doesn't really work like that, or even because in 1977 much of Doctor Who’s production budget was in BBC “man hours”, a nebulous concept with little real link to cash expenditure or real world economics. It’s also because inflation was falling for almost all of Williams' time on Doctor Who.

In fact, checking the RPI index for the 1970s, it's easy to see that of Doctor Who’s 1970s producers, Williams suffered by far the least from inflationary pressures. The all-time UK inflationary high of almost 26% (August 1975) was well in the past by the time he took charge, and in January 1978 as the last of these stories was transmitted, it dropped below 10% for the first time since the Oil Shock of 1973.

Now, disinflation is not deflation. Things were not getting cheaper under Williams, they were just getting more expensive at a slower rate. (Something those of us in the UK in 2024 will be familiar with). But it was a much slower rate than they did for Barry Letts or Philip Hinchcliffe, and even accounting for the fact that inflation is accumulative. Another inflation spike did hit in late 1979 towards the end of Williams tenure, but it would principally be a problem for his own successor John Nathan-Turner.

Ironically this spike was prompted by the June 1979 budget, the first of the Thatcher ministry elected on the 3rd May. This cut that top rate of income tax by 23% (and the base rate, paid by more and less well paid people, by a mere 3%), while committing to substantial cuts in public service expenditure to fund these tax cuts. The era of monetarism had begun. It is not unreasonable to assume that Robert Holmes and (future Conservative Party election candidate) Graham Williams approved.

Inflation would remain in high double figures from early 1980 until towards the end of 1982. In Doctor Who terms, it finally fell back to single figures during the production of The King's Demons. An age away from The Sun Makers. There are, as they say, many more tears over answered prayers.

These facts, of course, don't mean that Williams' seasons didn’t suffer from the effects of strike actions or the cumulative effects of BBC pay rounds made in order to combat similar at ITV franchises. A cost spiral of its own. Both these things could - and probably did - have a deleterious effect on his programme’s spending power, either in terms of actual pounds or “man hours”. But his off-the-cuff, go-to explanation, accepted uncritically by fans for four decades and seen in the wild on the internet following the release of this box set, is as flimsy as the walls of the pump room on Pluto and stands up about as well.

Underworld, with its likeable characters and performances, big ideas and outstanding model work, has a reputation as the worst serial of this production block. I disagree, as the sentence above has hopefully implied. Much of the serial's bad reputation comes from the decision to record its caves sequences in a CSO studio, against blue drapes onto which photographs of caves would be superimposed in camera. This is, of course, a primitive version of what we'd now call "green screen". With the emphasis on "primitive".

This was not as innovative as Underworld’s (other) defenders sometimes claim. Productions had been staged in a similar manner for some years, not least the work of the television pioneer James McTaggart and Doctor Who's own former producer Barry Letts. The decision was, in any occasion, made due to a budgetary error rather than for conscious artistic reasons.

It’s true that these scenes do not work visually. But it’s equally true that they’re not the whole of the story. Underworld also has a tremendously good spaceship set, and is cunningly scripted so it can be used twice, the P7E being a duplicate of the R1C. It also has a crackerjack performance by Alan Lake as Herrick (i.e. Heracles / Hercules) who imbues him with the roustabout qualities often found in the heroes of Greek myth, but often smoothed away in modern retellings.

It's also clear from the surviving studio tapes for the serial that by this point Tom Baker is directing what happens on the studio floor to an extent that muscles out the actual director Norman Stewart. This could be taken to be ego on Baker's part, another reflection of his increasing input into Doctor Who, but there may be more to it. Stewart had only recently qualified as a BBC staff director after a long career in production management. So recent that he was still in his former job when he was rota-ed onto The Invisible Enemy a few months before.

A handful of further directing gigs followed Underworld, including the Doctor Who serial The Power of Kroll. Until his disastrous direction of an episode of The Omega Factor (1979) required much of the episode being reshot by producer George Gallacio, and the abandoning of the episode meant to follow it in production in order to get that series' finances back on track. Shortly after this, Stewart was given no option but to return to production management if he wanted to remain at the BBC.

Underworld is also a story made with no involvement at all from Holmes, the first since 1974, and is thus the first idea of what Williams / Read Who might be meant to be like. It's here that we find certain things that will carry through into Doctor Who for the next two years. An interest in ancient myth and a connected one in repurposing it for use in Doctor Who. A fairy tale quality. A overall tone of amused distance. The harshness turned up to 11 in The Invisible Enemy and The Sun Makers has absolutely vanished.

It also seems relevant that the Minyans, whose quest for identity and sovereignty the Doctor accidentally becomes involved in, are victims of ancient Time Lord imperialism. The backstory of every season 15 story, bar Horror of Fang Rock, touches the Time Lords. The Fendahl are one of their ancient enemies. The Usurians have contemplated Gallifrey’s potential for economic colonisation. Even in The Invisible Enemy the wander around the Doctor’s brain leads to a discussion of Time Lord biology, his qualified immunity to the Swarm and eventually said Swarm’s plan to use his Time Lord abilities to conquer the Macro Universe. The Time Lords and their influence in the universe are never far away in Season 15. Something that sets the scene for its final serial, and which will be built on subsequently.

This is a jolly serial, devoid of sourness and of Holmes’ increasing misanthropy. It has no horror, only adventure. While Williams would later deny it, the influence of Star Wars, released as Underworld aired but a known quantity in the television industry before then, is very clear. (Williams had, along with Boucher and Blake’s 7 producer Maloney seen it at a preview months before its UK release, and months after its US one.) Not least in amendments to the camera script that add a laser gun fight over a chasm and a spaceship travelling over the camera.

Is it coincidence that, of all the fantasy / children's programmes on air Doctor Who was the best placed to take advantage of the UK public's imminent, inevitable Star Wars obsession? Or that Underworld saw the series' ratings leap back up after several months of relative doldrums? They'd stay high for the rest of the season too. (Other plausible reasons for this are explored by me here.)

The contrast with The Invisible Enemy is even more pronounced given that the two stories share writers, and I know which I'd rather watch. Baker and Martin, having started off on Doctor Who at the tougher end of the UNIT / army soldier era, have perhaps not received the credit due to them for their ability to adapt to the cosier version of the "earth exile" format, and then both the Holmes / Hinchcliffe horror years and the space fantasy sought by their successors. (If nothing else Russell T Davies recent admission that Wild Blue Yonder was heavily influenced by Underworld should lead to some sort of fan reassessment. No? Please yourselves.)

Season 15 ends as it began, and indeed as Season 14 ended, with a story written as a rushed replacement when another fell through. The Invasion of Time, a co-write between Williams and Read, and credited to the BBC in house pseudonym David Agnew, replaced David Weir's Killers of the Dark at a late stage. Like that abandoned script, The Invasion of Time is set on Gallifrey and is a direct sequel to The Deadly Assassin. What is also true of The Invasion of Time, and it would be interesting if Killers of the Dark was the same, is that it has essentially no horror content at all. That, combined with the setting, feels very deliberate. Like the idea was for this story to act as a flag in the ground for Doctor Who, with the production office announcing how much the programme had changed since the controversies of late 1976. Or maybe it’s just the logical end for a Time Lord fixated season.

David Weir was a longstanding colleague of Anthony Read's from his time producing The Troubleshooters (1966-72) who had also written for Space: 1999 (1975). He had been trusted to deliver something workable remarkably close to the production deadline, but what arrived on 15th August 1977 was something that could not possibly be produced on Doctor Who's budget. (Although maybe on Space: 1999’s.) Williams would later recall that it demanded an amphitheatre the size of a football stadium in which the entire audience consisted of humanoid cats.

Those Cat People, which costumier Dee Robson had begun designing (see above) were to be another species living on Gallifrey. In the absence of any surviving drafts or synopses, it is difficult to know more. But there is an intriguing possibility. Read and Williams' outline for The Invasion of Time does survive. In it the people living outside the Time Lords' dome are not, as they are in the finished story, Time Lord drop outs who have rejected, Tom Good style, Time Lord civilisation. They are the instead the indigenous people of Gallifrey, colonised by the Time Lords who eons before “offered… peace in return for the right to build their citadel on this planet". It is these colonised people who ultimately liberate the whole planet from another, newer occupation.

This idea builds on what we learnt in Underworld about the Time Lords' long ago meddling in the affairs of the planet Minyos, and the disaster that followed. Something said there to have led to their ostensible policy of non-interference. The interventionist Time Lord tyrant Morbius had been portrayed as an exception in The Brain of Morbius (1976) But these two stories together could have made him seem more the rule.

Perhaps the Cat People of Weir's story would also have been a species indigenous to Gallifrey, as well as one presently living on it? Additionally, it makes you wonder if Chris Chibnall read the synopsis in any of the books and fanzines in which it has been reprinted. Ascension of the Cybermen / The Timeless Children alludes to "Shebogans.. the indigenous people of Gallifrey". This combines Read’s idea with the longstanding (albeit atextual) fan conflation of this serial’s drop outs with the unspecified group “Shebogans” alluded to but unseen back in The Deadly Assassin.

As well as scripting problems, The Invasion of Time faced production issues. Caricaturing slightly; recent industrial action meant there was a backlog of BBC material and too little studio space in which to record it. Anticipated industrial action meant that light entertainment Christmas specials would take priority.

A six part Doctor Who serial would ordinarily have three studio blocks of two or three days each, plus a limited amount of pre-filming usually on location. The Invasion of Time was offered one, along with its retained location filming allocation. Head of Department Graeme MacDonald gently suggested that the serial be abandoned, and its unspent monies be rolled into the next season’s. Williams demurred. To get The Invasion of Time made, he would have to get creative.

The Invasion of Time shows Williams employing everything he’d learned over a year as a producer, even down to repeating the “one big set doubling as two near identical places” trick from Underworld, and then combining them with the writing and script editing that came more naturally to him.

Man hours in a pot designated for outside broadcasts (programmes recorded outside BBC premises but on videotape cameras rather than film cameras) were accessed by Doctor Who. This was unusual. While some drama had been made on location VT (e.g the Doctor Who serials Robot and The Sontaran Experiment) OB cameras were more usually used for reporting on large scale sporting occasions, news or Royal events, not least because they had, until very recently, needed to be used alongside a "portable studio" that took considerable setting up and was roughly the size of a small car.

OB cameras were booked for The Invasion of Time and scenes that would normally have been recorded in the studios that Doctor Who couldn't access were instead recorded on location. Specifically in a disused medical facility in Redhill, Surrey. Some were shot on extemporised sets, built inside the corridors and wards of the empty building. Others were simply recorded in rooms that seemed roughly suitable for the action that the story required to be staged.

Given the speed with which it was written and the production nightmare, it’s remarkable that it’s as good as it is. Which is, most of the time, very good indeed. Certainly its producer / co-author remained proud enough of it to suggest it as an early Doctor Who vhs release half a decade later, and editing notes for cutting the serial down into a 90m cassette version still exist. (If someone with the skills could get on that, I’d be grateful.)

These days the incoming showrunner of almost any series would be expected to write at least one early episode of the new series of their programme to demonstrate what it should be like. The Invasion of Time shows the wisdom of such an approach. With it, the Graham Williams version of Doctor Who actually arrives. This is, broadly, the programme he'll be making for the next two years. Even the young female Time Lord Rodan is a de facto prototype Romana, a character who'd appear in every Doctor Who story Williams made after this one.

They may have had to have descended to the Underworld to find it, but this is Williams and Read finally making, broadly, the Doctor Who they want to make. Not the Doctor Who Robert Holmes had left behind. A stab is even made at unity across the season by making the antagonists of this finale the Sontarans, mentioned in the series’ opener as the enemies of the Rutans featured there. Doctor Who's cosmology is joining up, even if he's not yet looking for the Key to Time. A few more lines would have added to the effect. Perhaps if the Doctor’s defeat of the Rutans on Earth had allowed the Sontarans to achieve victory in their eternal war, and because of this they have moved onto invading time? Thus the Doctor would have to head home to defend his own people in secret and because of his own actions.

The demands of Read and Williams' scripts prompt another outrageously great performance from Baker. With his character presenting as antagonist as often as protagonist, feigning madness for much of the first three episodes, and unable to communicate either his plan or the desperate situation which has prompted it to other characters (or the viewer) due to his enemies' mind reading abilities, there is almost no space for him to fall back on the tics of his four series in the role. Even if he’d wanted to.

Separated from Louise Jameson for almost all of the story, he instead finds foils in John Arnatt's brilliantly astute performance of Borusa as the consummate politician, and Milton Johns' glorious turn as oleaginous political time-server Castellan Kelner. All three are terrific, but there's an argument that the Doctor had never been quite so absolutely central to a Doctor Who story as he is here. Many Doctor Who stories are about a crisis the Doctor arrives during and resolves despite having little stake in it. They are essentially procedurals. This one is about a crisis the Doctor himself provokes in order to resolve it, and while under emotional stress, because he has no choice. The only alternative is the destruction of the home he abandoned but which he still clearly has emotional ties to.

Baker had long had input into the series, but the shift in production teams had seen that input increase, partially by accident and partially through Baker’s own deliberate efforts. The nature of The Invasion of Time emphasises his importance to the series. It’s also not an exaggeration to say that almost every single line of the Doctor’s dialogue in the later stories of this season was amended by Baker in rehearsal, and this is reflected in the handwritten amendments to their final scripts.

When in this serial, and the season's, final scene the Doctor, alone in the TARDIS after the departures of Leela and K9, looks straight down the camera and beams, it seems like an acknowledgement of where power is really vested in Doctor Who after a year in which every moving part except Baker had been changed. Harnessing the actor's creativity and star power had been key to the success of the season's best serials, but it was also storing up day to day problems for the immediate future.

Like a lot of people in their mid teens, the fifteenth season of Doctor Who doesn’t quite know what it’s doing or what it wants to be. It’s experimenting with and inconsistent in its politics and its mood constantly shifts. It’s looking for new places to go and new people to be with. It’s also at times not really suitable company for children or adults. There's a lot of ego thrashing about here. But catch it on a good day, and you’ll find it’s great thing to spend time with. Often witty, inventive, capable of sudden insight and keen to try new things.

It just needs a little time to mature.