"Mindwarp" (The Trial of A Time Lord Parts 5 to 8)

"We can't go on together, with suspicious minds."

Seen: 4th - 25th October 1986

The Long Way Round

If the first section of The Trial of a Time Lord found Doctor Who feeling, if vainly, its way towards a new style and a new status quo, the second finds it charging back in the direction from which it had come. Mindwarp, the title for the four episodes transmitted as The Trial of a Time Lord Parts 5 to 8 until relatively late in production, is a direct sequel to 1985's Vengeance on Varos. It has the same writer (Philip Martin), the same director (Ron Jones) and a returning villain in capitalist exploitation-eer Sil (Nabil Shaban). It also has much of the bleak, blackly comic tone, and many of the same themes and concerns.

Doctor Who's script editor / head writer Eric Saward had been very keen on Varos, and despite his initial suspicions of Martin (whose credits included Play for Today) as a writer unsuitable for Doctor Who, producer John Nathan-Turner had become a great enthusiast for Sil. Sil's return, discussed with Shaban before Varos even went out, was a foregone conclusion. A follow up featuring the character, provisionally entitled Mission to Magnus, was commissioned and scheduled for the 1986 series of Doctor Who. It was then cancelled along with the rest of the original 1986 run as part of the series’ mid 1980s production upheaval known to fan historiography as "the hiatus," and Martin was asked for another story, one that would fit in with The Trial of a Time Lord concept.

That wasn’t surprising. By that time Martin had become sufficiently part of the Doctor Who rep of the day that he even wrote the baffling Invasion of the Ormazoids for the Make Your Own Adventure With Doctor Who range, a short-lived attempt to marry Doctor Who with the 1980s craze for gamebooks for older children. (Of which I have written something else here.) More, the production file for this serial has correspondence from Martin indicating a warm relationship with both Saward and Nathan-Turner, and references to Martin attending one of the serial's studio recordings. These are things that were rarely the case in mid 1980s Doctor Who. Saward and Nathan-Turner did not see eye-to-eye, with the former at times seemingly jealously guarding his roster of freelance writers as a kind of alternative power base.

It's one measure of the extent to which Sil had been judged the great success of the 1985 series of Doctor Who, that even after all this production disruption, everyone knew a reappearance for the character was inevitable. Another is that before this story was even called Mindwarp it was commissioned under the working title/description betraying the motivation of that commission: The Planet of Sil.

The (home) planet of Sil is where the Doctor and Peri arrive in the evidence from the former's recent past shown to the court in which a now companionless Doctor is on trial. Unusually for this period of the series, they have arrived there not just deliberately, but with a specific mission. Having become embroiled, off-screen, in the affairs of the planet Thordon, the Doctor has discovered that Thordon's warriors have been supplied with phaser weapons, centuries beyond their own technological ability, by arms dealers from the curious pink-oceaned world, Thoros Beta. The Doctor has decided that this arms-dealing must be stopped.

Before long, Sil has had the Doctor tortured for information and while he and the Peri quickly escape with the help of the "barbarian King" Yrcanos (Brian Blessed) the technology used to extract information from the Doctor's brain has seemingly had an effect on his personality. He quickly betrays friends old and new, seemingly for no purpose, and then arbitrarily commits himself to helping the mad scientist Crozier to find a way to transplant the brain of the dying Lord Kiv, Sil's boss and the capitalist super brain of Thoros Beta, into a new body. After all, it's vital that the Mentors of Thoros Beta continue their economic exploitation of nearby parts of the galaxy.

As in the previous segment, it's as if a bunch of characters in Doctor Who have gathered to watch Doctor Who. But unlike in the previous segment, something is actually made of this. It seems the point, rather than an inadvertent result of a formatting error. Because meta-fictionality, whether in terms of simple fourth wall breaking jokes or defiantly non-literal storytelling, are very much things that are in Philip Martin's personal wheelhouse as a writer. He likes putting things on screens and letting characters comment on them. Even before the Doctor on Thoros Beta is put through what is surely the "mindwarp" of the title, the Doctor in the courtroom has denounced comic relief scenes on its screen "inconsequential silliness".

Later the Doctor on the screen declares "I could do with a laugh!” before another comic scene, while Peri comments on “...actors playing over the top in politics”, with the script there managing to pre-emptively comment on both the heightened performances it's asking for and get in a swipe at the then President of the United States. Martin doesn't just do this kind of thing here, when enabled by the Trial format, it's something integral to his approach to Doctor Who; he's all over it in Varos and even in the abortive Mission to Magnus.

(Briefly, to serve the point, while Magnus was never made for television, Martin later novelised the scripts and later still adapted them for audio. In either form it is by far the least of Martin’s stories, but it nevertheless plays with his usual preoccupations. At one point Sil and the Magnusians capture the TARDIS and travel forward in time until later in the story. There they worry about waiting for the other characters to catch up with them. This also (seemingly) places them, and the audience, in the position of knowing what happens before the (other) characters. Again, as on Varos and in Trial, we find characters sitting watching a screen relaying another part of the story they’re in, and commenting on the action. To make matters weirder, in this case it’s the TARDIS scanner.)

The core of Mindwarp as a story is how it makes use of the Doctor's amnesia concerning recently events, only briefly referenced in earlier Trial episodes, an essential part of itself, something which enables the Doctor's failure to convincingly dispute a chain of events in which he presents as a murderous coward, a traitor and a villain. As Martin seizes the opportunity, largely untouched elsewhere in Trial, to turn the Matrix, with its evidentiary function, into an unreliable narrator.

This should link into the broader point of the Trial, in that the original audience was destined to discover in a couple of months time that the court prosecutor, the Valeyard (Michael Jayston) is a future incarnation of the Doctor working to his own and very different agenda. We know Martin knew this because he was present at the story conference in 1985 when the plot point was discussed. (Notes made in it by David Halliwell, another writer who was present, but whose story was ultimately rejected, survive to be read.)

In Martin's scripts for Mindwarp, to a far greater extent than in Robert Holmes or Pip and Jane Baker's episodes featuring the character, the Valeyard’s verbal attacks on the Doctor seem motivated by a kind of self loathing. In a different, more sophisticated, version of the overall Trial storyline, there would be questions as to the reasons why Jayston's future Doctor despises Baker's present incarnation so much. How important are events on Thoros Beta to the Doctor's corruption? Is the Valeyard angry with the Doctor because his, which is after all their, behaviour gets Peri killed?

What hinders the story is that said behaviour is only slightly more outrageous than his average conduct in the 1985 series, and probably doesn’t quite touch the extremes of his first serial The Twin Dilemma (1984). On the DVD commentary for the Trial writer Philip Martin seems unaware of this, and talks about how he intended this serial to be shocking, for it to be a unique questioning of the Doctor's character, motivation and personality.

For all this story's impact, it's not hard to imagine how much greater it would have been had it come as a complete surprise. Had it come at almost any other point in Doctor Who's history than this. Imagine Mindwarp at the midpoint of a Tom Baker season. Or after a Colin Baker season in which the Doctor had been written in a more orthodox manner.

Oddly, the Trial conceit, which allows for cutting back to the Doctor in the courtroom, and seeing him anguished and protesting, allows the audience, and indeed actor Colin Baker, some respite from the Doctor's extreme behaviour. Which The Twin Dilemma doesn't. But the Doctor's treachery still leaves a hole where the protagonist of the adventure on Thoros Beta should be. Or would, if the story didn't have a ready made alternative to hand: King Yrcanos of the Krontep.

Yrcanos is the last of Saward’s replacement Doctors. Heroic characters he finds more plausible than the Doctor and played by actors he likes more than Colin Baker. Yrcanos is certainly the closest thing the serial as transmitted has to a protagonist in its middle half, as the Doctor freaks out, assists with Crozier's murderous experiments, and seems to change side more than once. At the opening of the second episode Yrcanos steps, quite literally, into the action to save the Doctor and Peri's lives, and as soon as the Doctor is rendered insensible by his trip through Crozier's brain moderator. By the end of the story he has achieved the Doctor's aim of dethroning the Mentors and destroying their business empire, as much despite the Doctor as thanks to his help.

Yrcanos is vain, violent and verbose. His ultimate ambition is to die in battle. But he is also concerned with the liberation of the enslaved and the demolishing of arbitrary authority. He is funny. He is brave (and not just in battle but also when tied and expecting to be cold-bloodedly executed). He even has a strange, sincere spirituality, evidenced as he explains his culture's concept of reincarnation to Peri in a peculiar attempt to comfort her. He's also one of the biggest performances ever given by Brian Blessed. Who is BRIAN BLESSED. (The great Morgo be praised.)

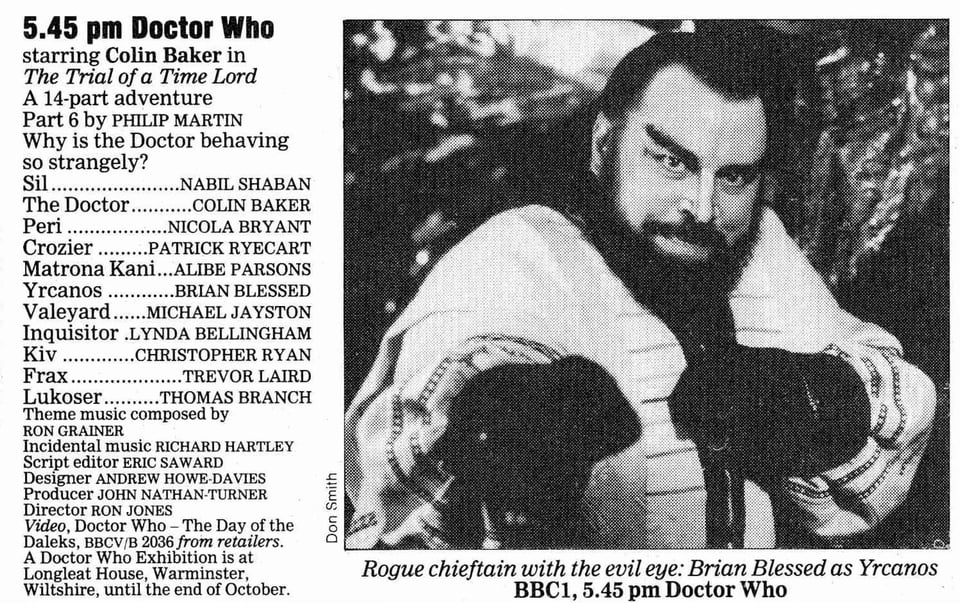

Blessed is, of course, a great actor as well as a proper Guest Star. One more than capable of taking the weight of 25-to-50m of teatime space adventures on his shoulders in the absence of its above the title star. But it remains odd that he is the last in a long line of actors to be asked to do so in then very recent times. In which context it seems not at all surprising that Radio Times' billing for the second part of this serial was illustrated with a picture of Blessed, rather than Baker.

Other casting for the story is strong and for old money Doctor Who unusually diverse. Some of this demanded by the script. Some isn't. Matrona Kani is described as "black, beautiful" in the script, and it may be that Martin was specifically thinking of the sly, statuesque Alibe Parsons, who was eventually cast. (She had had a leading role in his Gangsters (1975-77) and was known to SF nerds from her role in Space: 1999.) Tuza too is specified as requiring a non-white actor. This is not the case for Frax. But casting all three, alongside almost all the extras for the serial, means that on Thoros Beta the default human being is not white. The Doctor, Peri, Yrcanos and Crozier are marked out as outsiders to this society by their skin colour.

An argument has been made that this makes Thoros Beta a world of Flash Gordon cliche, equating alien with non-whiteness, or that the extensive use of non-white actors as a servant class represents something dubious about the production. Certainly, there are moments in the story when Sil is carried around by bearers, played by non-white, non-speaking actors, that might on the surface give us pause. But Sil himself is played by a British Arab actor. The Terileptil ambassador by the Kenyan born British Indian actor Deep Roy. We just can't see that because they're both under heavy prosthetics. There's a lot of work here for not-white actors, in all kinds of roles.

Yes, an ethnic homogeneity amongst a servant class is something a production should be sensitive too, and which might make an audience uneasy, especially if it were done unthinkingly. But it's clearly not done unthinkingly. Frax, for example, is a really good supporting part for any actor. Far better than (to take a random example) Maxil, the similar captain of the guard role in an earlier Doctor Who (Arc of Infinity) which brought Colin Baker himself to John Nathan-Turner. Frax has a genuine strategic intelligence, evidenced by his monitoring the rebels' weapons' dump so that he knows their movements, rather than simply confiscating it, as well as his waiting for the Doctor in the control room at the end. He also has funny lines ("You're obsessed with dying, Yrcanos. I don't know what's the matter with you.") He's also the only person to show compassion for the Raak when it's killed, describing its death as "murder" and noting that the creature was "proud" of its work.

It's another nuance, although nothing can change that all this skill and personality is ultimately is put in the service of the Mentors. Mentors, what a brilliantly telling, presumably self-applied, description that is for people whom Martin has explicitly described elsewhere as "colonial power". Frax ends up killed by Yrcanos and mourned by no one. But the character is a deft portrait of a kind of colonial collaboration. Someone intelligent and motivated who feels they have done well out of occupation, but who is nevertheless themselves exploited. (Some have criticised actor Trevor Laird's deadpan delivery as monotonous, but given the vocal range he's displayed elsewhere in his career - including as Martha's Dad in the 2007 series of Doctor Who - this is clearly an actorly choice. Laird knows this is a funny part.)

It's because of things like this, as well as the broader context of Martin's own other work, that we should be looking for complexity rather than reductionism in terms of such things in Mindwarp. (Although engagement with genre cliche in order to parody it with a straight face is another plank of Martin's writing.) Gangsters is a series that engages with colonialism, immigration and racism in the context of organised crime, and does so with subtlety and complexity, while featuring terrific roles, sympathetic and unsympathetic, for "ethnic minority" actors. Mindwarp is an extension of that, and the scripts for Mindwarp are assuredly Martin scripts, principally the work of their credited author, to an extent not always the case in mid 1980s Doctor Who.

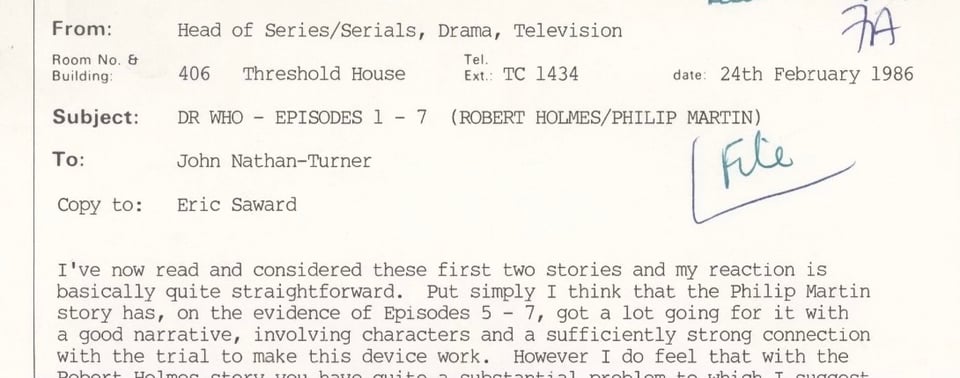

We know that BBC Head of Drama Series and Serials Jonathan Powell approved Martin's scripts with no changes when he read them. Eric Saward recalls doing little work on them, and Martin suggested (again on the commentary) that Saward's work was largely devoted to continuity related matters in the courtroom scenes. The surviving production scripts throw up very few textual variations within them, and there is little difference between them and the finished serial or indeed between the serial and Martin's 1989 novelisation.

At a convention in the 1990s I asked Philip Martin about the limited number of (to me specific and interesting) differences between his novelisation of the story and its presentation onscreen. His answer was that he had written the book from the last scripts he sent to the production office, rather than the finished programme, and that with the exception of the epilogue he had conceived while writing the book, any differences between the scripts the book was based on and the episodes as made were nothing to do with him.

That was a brief conversation in an autograph queue. You'll have to take my word for it. (I didn't record it and I can't project it onto a screen for us to debate its veracity.) But if the book does essentially represent a very slightly earlier stage of the serial's composition then a brief run through of the differences is probably a good idea, just to illustrate what a minimally edited Doctor Who script looked like in 1986.

The first half of the story is more or less the same in both formats. There is some additional dialogue in the book, but apart from an additional scene in the TARDIS early on, it has the same scenes in the same order as the television serial. Watching the episode after reading the chapters you would be struck only by minor differences, mostly explicable as deletions, and an inattentive viewer / reader would notice little deviation at all.

The most interesting points are that the Keeper of the Matrix, a character not introduced in the televised serial until Part 13, is briefly present in the courtroom scenes and is given the name Zon. This is easily explained. Halliwell's aforementioned notes and the writers' guide issued to everyone working on the season both indicate that the Keeper's presence throughout proceedings was envisaged at an early stage of the Trial's development before being decided against. (In Parts 1-12 of the finished serial the Matrix is operated by an extra.)

There is also, in the book, a moment when the Doctor is specifically charged with "crimes against the inviolate laws of evolution". Gallifrey has a specific issue with what the Doctor did on Thoros Beta rather than just his propensity for intervention. This was deleted, perhaps to allow space for the brief discussion of events in Robert Holmes' episodes that is present in the televised scene, but not the novelisation.

The third episode has the most differences, but this amounts to some reordering of scenes caused by the cutting of an extraneous court scene (which was nevertheless recorded and is on the Blu-ray edition) and examples of what Martin Wiggins has called “shredding”; Saward's by then half decade long habit of cutting a pair of long scenes into between four and eight shorter ones which are then interlarded, in an attempt to quicken a script's pace. There is a change of emphasis in the scenes where Yrcanos bargains with the Thoros Alphan resistance. In the book, they threaten to kill Yrcanos only as a test, to establish that he really is who he claims. Onscreen, the threat is genuine.

Looking at this section of both script and book also allows us to concur with Martin's conclusion on the commentary track on the disc releases that Crozier calmly finishing his tea as Kiv goes into cardiac arrest and before administering CPR is a brilliant piece of actorly business by Patrick Ryecart rather than something from the writer's own head.

Elsewhere in that commentary there is greater ambiguity. Martin suggests that it's possible that the third Mentor figure, the elderly and worried Marne (his name in the book, onscreen he doesn't have one) was added by Saward as "I seem to remember we were under-running". This may be true, but in the book, and the scripts, Marne appears more, not less, than he does onscreen, being introduced in the second episode's scenes in the processing plant for enslaved workers, rather than not being introduced until the final episode. These again feel like deletions and perhaps if Marne was added by Saward, it was at an early stage of the story's writing.

In relation to the recalled under-running: The production file also has a record of Martin being commissioned to provide additional material for the middle two episodes due to an underrun, most of which ends up not being used. It may be this detail about the episodes being short that Martin was struggling to recall.

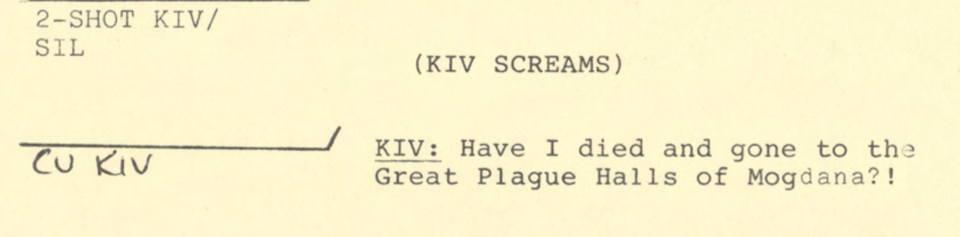

Other minor changes include names. The rebel known as Vern is Ger in the book (and presumably Martin's earlier script). Both Yrcanos and Kiv referencing the same mythology "the plague halls of Mogdana", mentioned in Doctor Who - The Discontinuity Guide as an example of how the Mentors may have corrupted Thordon's culture with their own, is two separate references in the book. Kiv worries he is dead and in the "belly of Sanscrupa". (Intriguingly there is noticeable physical evidence of tippexing and retyping on the BBC's archive scan of this page of the script.)

The final quarter of the story is again a close match in both formats, with equally few and equally simple cuts to dialogue, until the penultimate chapter has the Valeyard say that the third and final section of the prosecution "..the future" would follow. On television the third "segment" of evidence is the Doctor's defence presentation, but again we can find support for Martin's approach in Holmes' first draft of Part 13, where it is again stated, this time in the past tense, that the third segment was part of the prosecution's presentation. (Again, this is a strong circumstantial indication of the truth of the book being composed from scripts that pre-date those used for the final programme.)

One thought-provoking dialogue change between the book and the final serial is a line given to Sil. Originally rendered as "Like you Doctor I endeavour to maintain a certain continuity of behaviour." onscreen Shaban delivers "I endeavour to maintain a certain continuity.” While a shorter line, this is also a broader statement. Both versions clearly refer to the serial's engagement with unreliable narration, but the former is more pointedly directed at the Doctor's out-of-character behaviour. Or at least designed to draw the audience's attention to it.

It's a way into the question of what actually did happen on Thoros Beta. Of how much of what is shown on the courtroom screen really happened and why. Or is it? There is, of course, an argument that it doesn’t matter what really happened on Thoros Beta, that the confusion, the Doctor’s distress, is enough on its own. That it is all fiction. There is no reality. That the effect alone is the point. It's a sound one, and one that would naturally occur to anyone who'd glanced at much of Martin's other work. To ask what aspects of East of the Equator, the finale of Gangsters "really happened" would be a question as meaningless as its title, and not as deliberately.

But Doctor Who is a less arty series than Gangsters. It is required to be accessible to children and families and exist in a broader context, both of an ongoing continuity which is the work of many hands, and of characters who pre and post date any individual story; and it does seem that explanations were worked out by Martin, if not provided to the cast or all of the crew.

Philip Martin says on the commentary on the serial that his core idea was that the machine used to try and extract the information about the Raak from the Doctor's brain had recently been used on Yrcanos (and we indeed see this happen earlier in the episode) thus the Doctor's out of character behaviour is related to the machine. He has inherited both Yrcanos' bloodlust and the subservience to the Mentors' cause that Crozier is trying (and failing) to impose on the King. (Or as Peri literally says when the Doctor interrogates her on the rock of sorrows, “I thought the brain transfer impulse had made you crazy”.)

The inefficiency of the machine is also seen later in the story; it's the reason that Kiv, when transplanted into the body of the "catcher of sea snakes", suddenly starts using nautical and fishing terminology when discussing other things. (It seems that Crozier's machine is simply not very good.) Once we have this piece of information from Martin, there is a visible arc in the writing and performing of the story that supports this interpretation. The Doctor of the second episode is barely coherent, while that of the third episode does not behave as broadly or as outrageously, yet he does do things for reasons we can't ascertain.

It would be easy to see this as him calming down, slowly working his way back towards his normal personality through the confusion, rage and paranoia the machine has pumped into his mind. He is, metaphorically speaking, no longer drugged out of his mind, but his judgement is massively impaired and his priorities severely skewed. If this is the case, and the sole explanation for what happened on Thoros Beta, then the courtroom Doctor’s attempts to explain his actions as "a clever ploy" and "a plan" are the character ex post facto rationalising behaviour he cannot accept. As is his insistence that the Matrix itself has been compromised and is showing things that didn't happen.

It's a position that fan responses have not so far quite considered. That everything we see onscreen is true. The Matrix is not lying and the Doctor in court is desperate and mistaken. Of course, part of the reason for this, is that we all know that Saward instructed Pip and Jane Baker, who were writing the next evidence segment, to include the idea of the Matrix faking evidence into their story and because of this, it straightforwardly does so. But going by Mindwarp alone and Martin's comments the very opposite interpretation is just about plausible.

Yet a television programme is inherently a multi-authored text, and Colin Baker has said repeatedly since this serial was made that, unable to get an answer from Saward as to whether the Doctor's actions were the result of his brainstorm, a deception on his part, the Matrix lying or some subtle combination of all three, he decided that "None of this happened, the Matrix is lying" was the most efficacious for him to play. That decision by the lead actor, combined with developments in later episodes of the Trial where the Matrix objectively has to be lying, seemingly demands we seek multiple, overlapping "explanations", or at least interpretations, of the events shown on the Matrix screen, with no certainty as to ever arriving at a complete answer.

I am tempted to argue that in retrospect it’s relatively easy to see that some scenes are invented by the Valeyard. That it's every time the evidence contradicts itself, not when the Doctor disputes its veracity. For example, in the second episode we cut from Sil happily accepting that the Doctor is now on his side to him screaming that he does not believe it, as his bearers point their guns at the Doctor. That is Sil failing to observe a certain continuity of character, and it feels pointedly deliberate. We might assume that the scene on the rock of sorrows too is partially invention.

But all of this is deliberately unknowable. You could not cut a coherent version of Mindwarp without the trial scenes together, as you could for The Mysterious Planet and has been done for "Terror of the Vervoids" (it's on the Blu-ray). There is not a straightforward version of the story that does not make complex demands of its audience in terms interpretation hidden inside the material that was shot. Ambiguity is integral to, inherent in, its nature.

In the final episode, matters of interpretation initially seem to be being put to one side. The Doctor, suddenly acting completely normally, frees Yrcanos and with him initiates a revolution at the first moment he can. Perhaps because of how he must be characterised in the second and third episodes of this segment, the Doctor is more than usually heroic under Saward's editorship in the first and last. Even if the story does end in the character's most shocking failure of this, or any other, era of the programme.

Fan history holds that the death of Peri in the final episode of this segment is an impressive end for the character. But while the scenes in which Peri is possessed by Kiv, and then Kiv is killed by a despairing Yrcanos, are dramatic and impressive, Mindwarp is not a good ending for Peri. It’s a good ending for Nicola Bryant. Which is not quite the same thing. (Philip Martin has spoken of feeling a need to give Bryant “things to do” in her final episodes). Bryant is great at playing Kiv-in-Peri's-body. But that's by definition not Peri at all. The last we see of the Peri herself is her protesting as she’s chloroformed before surgery. It's tragic. Upsetting. But it's sad without being poignant.

Thematically, it also puts us in a difficult place. After the shock and drama have subsided, we're left with the fact that Doctor has, either through callousness or incompetence, through madness feigned or real, got Peri killed. This might be seen as a clever reversal of the situation in The Caves of Androzani, where his previous incarnation dies to save her, but it's much closer to a kind of tawdry negation of it. One that isn't helped by the Doctor's post regeneration bullying and even assaulting of Peri, which leaves their relationship in the 1985 series uncomfortably close to abuser and victim, seemingly without the production team noticing.

If this were deliberate, if it were the point, then okay, very well. But by giving that story this ending, questions about the Doctor's attitude and behaviour arise that require more engagement and bigger answers than The Trial of a Time Lord is willing, perhaps capable of providing. The revelation in Part 13 of Trial that the completion of the operation and Yrcanos' massacre of those responsible for it is one of the pieces of evidence "faked" by the Matrix is regarded by fan historiography as a cop out. I disagree. It is the only possible resolution to this story point on almost all levels.

In plot terms, the clues are there. We know from elsewhere in the story that the Matrix's information is relayed through the bugged TARDIS. But by the time Yrcanos enters the lab, the TARDIS has left Thoros Beta. By the story's own logic, what we're seeing must be fabricated. This is something that makes sense of how Crozier has conducted a very different experiment to the one from the previous episode, transplanting Kiv's consciousness rather than his physical brain.

On the screen, we see how Yrcanos and Tuza are trapped in a time bubble by the Time Lords before the final assault on the laboratory. This is surely a contrivance of the Valeyard's to hurt the Doctor? What does it achieve but making his earlier self watch horrified at invented scenes in which Peri is possessed by Kiv. Had the time bubble not been used, the rebels would have been in time to save Peri.

Which is to say, they were.

Right from the earliest stages of planning Trial Eric Saward considered it to be a Doctor Who version of Dickens' A Christmas Carol, with past, present and future sections and a redemptive coda. In this context, the revelation that Peri did not die redeems the Doctor’s past behaviour as surely as Tiny Tim’s survival indicates Scrooge’s good future behaviour. The Master's "She lives" is an exact parallel to Dickens' "Tiny Tim, who DID NOT die." It fits the overall scheme far too well to be an accident. It's the actual point of everything that happens in Mindwarp.

But here's a problem. While every fact above (e.g. Saward's A Christmas Carol influenced intentions, textual inconsistencies, etc) is true and citable, the emphasis I've put on them has created something that is in some senses demonstrably false.

This is certainly how I see the story, and I genuinely think it is the only way that this text can "make sense". But it's in no way the intention of anyone involved in the making of it. It's not what anyone wanted or planned.

Martin, Saward, Baker, Bryant and Nathan-Turner all initially agreed that Peri should die. The decision to reverse that was made after it had been shot. It is something that all those of the above still living regret. (I don't.) But all the "clues" as to how Peri must have survived above would be present in the finished episode even if Parts 13 and 14 had not had lines added to them to say that she did.

Which shows how little you have to slant something, and how little you have to leave out, in order to present a story about an event that contains no outright falsehoods, but is in important ways untrue.

Unreliable narrators, eh. We get everywhere.