TIME IN REVERSE

“But is tomorrow yesterday? Or has it been and gone today? I wish someone would say.”

In the July 1994 cover dated issue of Doctor Who Classic Comics1 Marvel UK reprinted Time in Reverse, as the untitled story originally run in TV Comic in 1965 had been christened by fans in the intervening years. It was, deliberately or otherwise, printed coinciding with the twenty ninth anniversary of the original printing and I had no idea this story even existed when I read it. I was enjoying the mid 1960s strips written and drawn by Neville Main, despite the distinctly fourth billing they tended to receive in the magazine itself. I had already become a big fan of Hartnell era Doctor Who through the VHSes, and it’s fair to say Time in Reverse blew my mind a tiny bit. Just the idea that it - a children’s comic strip from 1965 that works read both backwards and forwards - could exist at all, blew my mind a little bit. It still does.

In 1991, and for the same birthday I got The Caves of Androzani on VHS, I had received the video of the first half of Red Dwarf III, the first episode of which was Backwards. This was hugely celebrated on transmission, although has fallen from favour a little since. I liked it when it was first on, and while I wasn’t so naive that I thought that this was the first time anyone had ever done such a story, I had thought (I swear I did think this on transmission) that it was a shame that Doctor Who hadn’t been able to do something like this first, so that the story being told had been able to be a bit more complicated and a bit more serious. It’s not a worthy thought, but it’s the kind of thought about storytelling that teenagers had. Little did I know.

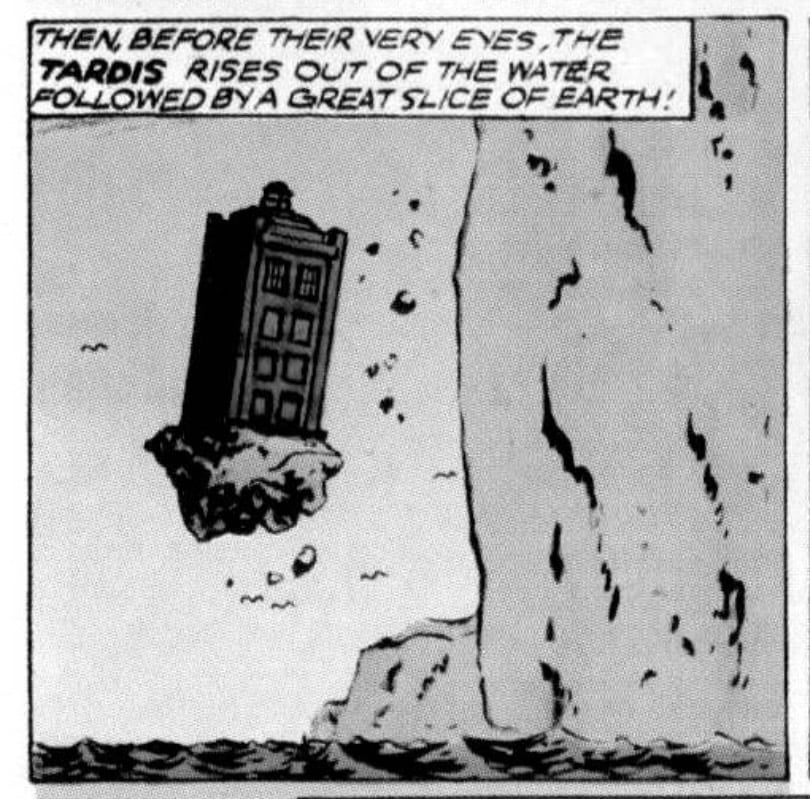

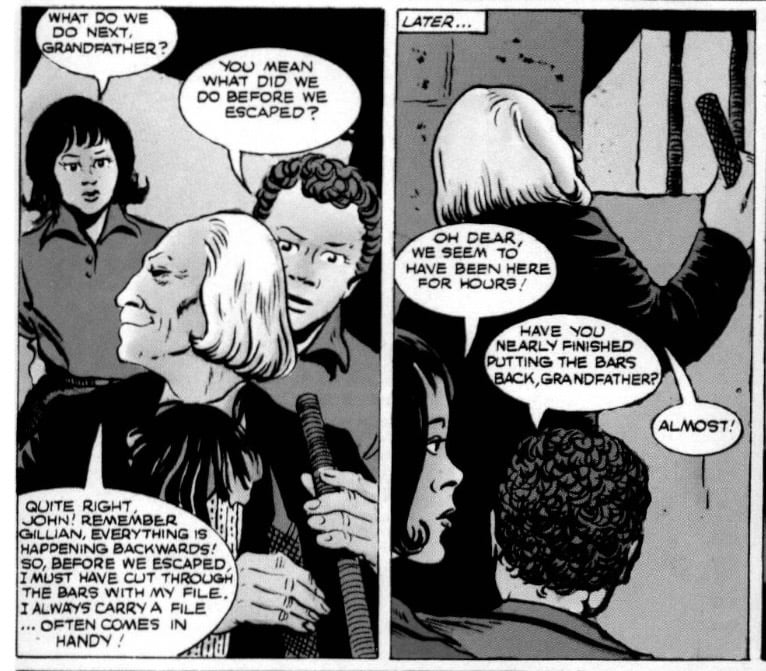

Very few 1960s Doctor Who stories comfortably sit into “sideways”, ostensibly the third major category of the series after the far more self-explanatory “past” and “future”. The Edge of Destruction of course. The Space Museum (which even replicates The Brink of Disaster’s “broken spring” explanation at its conclusion)2 so it’s both odd and encouraging that the much neglected TV Comic strip should provide us with another example in its own untitled “backwards”, story printed from 9-23 August 1965. Looked at the right way round Neville Main’s story is a distillation of 1960s Doctor Who down to its essence. The TARDIS arrives somewhere, its crew are separated from it, accused of something, captured and escape back to the TARDIS.

What the author grasped in this instance is that the story told using such a conceit needs to be simple, really consisting of a number of self-contained incidents that reinforce the conceit, otherwise the form doesn’t so much overwhelm the content as de-stabilise it. Sustaining something like this, something that can read in two directions and without cheating, is difficult.3

Selling a story told this way to an audience, even a discerning audience, is not easy. Sondheim’s musical Merrily We Roll Along (1981) has been periodically revived and to much acclaim, but it was a failure when originally staged. It may even owe its own existence to the success, amongst a much more limited audience, of Harold Pinter’s 1978 play The Betrayal (which fictionalises the author’s extramarital affair with the presenter Joan Bakewell but in reverse order) as the earlier play of the same title on which it’s ostensibly based.

George Kaufman and Moss Hart’s 1934 play Merrily We Roll Along is the near forgotten precursor to Sondheim’s later musical of that title. It has the same reverse chronological structural conceit. But no songs. Despite fantastic reviews it was a box office failure. But the narrative mode it if not created then certainly adopted on a large public stage of the first time had, ironically enough, plenty of implications for the future.