It Takes You Away

Anyone who thinks Psychic Paper skipped a week in the last few days is right. Apologies. To make up the difference, there will be at least two e-mails for paid subscribers this week, probably three. They start with a Guest Post looking back at the show’s recent past. Now the first season of the RTD / Gatwa era of Doctor Who has come to a close, it’s time for Phil Purser-Hallard to take us back four and a bit years to a highlight of the first season of the Chibnall / Whittaker era of Doctor Who, Ed Hime’s debut script for the show, and the second episode made in that production block, It Takes You Away.

Take it away, Phil.

“She asked me to stay and she told me to sit anywhere, and I looked around and I noticed there wasn’t a chair.”

‘We’d know if we were vampires, right?’ Ryan nervously asks his step-granddad Graham in the Doctor Who story It Takes You Away (2018), as the two stare at a mirror which is failing to supply them with the expected reflections.

Ryan and Graham are not vampires. But if they were, the twist would not be hugely more outlandish than those the story opts to take instead. What begins as Scandi-horror, about an isolated young girl terrified of a menacing presence in a Nordic forest, swiftly changes tack to become a portal fantasy about a magic mirror leading to a nightmare realm, then a cosy ghost story about two living men reunited with their dead wives, and finally a cosmological science fiction parable about an exiled universe that longs to rejoin with our own.

It's quite a journey. In brief, 14-year-old Hanne’s feckless father, Erik, has gone to join his dead wife, Trine, in the parallel world he has discovered behind the bedroom mirror in their remote fjordside cottage. To keep his blind daughter ‘safe’ at home in his absence, he has convinced her that the forest outside is home to a monster, even rigging up a sound system to generate its supposed roars. When the Doctor, Yaz, Graham and eventually Hanne follow Erik through a terrifying ‘Antizone’ into the peaceful mirror world, they find that Graham’s wife Grace, like Trine, is apparently alive there.

The Doctor realises that they have entered the Solitract, a part of the primordial universe that was separated off as it was incompatible with the rest, and that Grace and Trine are illusions this sentient realm has generated. The Solitract has been mimicking Graham and Erik’s loved ones simply because it wants company, but in the end it must expel everybody, even its new best friend the Doctor, to avoid being destroyed by the incompatibility.

Amid all this rapid genre-shifting, the episode clings to the trappings of a fairytale, where motifs like forests, mirrors and transformation into a frog (the form ultimately taken by the Solitract) are standard. For all its plot-complicating hazards, the Antizone is a kind of bridge, complete with lurking troll, and even the cosmogony that underpins the plot – reminiscent of the Norse myth of Muspell, a separate realm of eternal chaos that outsiders can never enter and that can form no part of creation – reaches us in the form of a bedtime story the Doctor remembers being told by one of her grannies.

The shape of the story is also a familiar one. In the end, It Takes You Away is about overcoming the perils and temptations of a fantastical otherworld and returning to reality a wiser person. When Graham sees that Grace’s ghosts has no interest in Ryan’s welfare, he realises that she is an imitation, and makes the painful decision to leave her and protect her grandson instead. He comes to understand that loving the living is more important than yearning for the dead, and is rewarded by a greater level of acceptance from Ryan.1

Erik seems to undergo a similar change of mind, although we see little of the internal process that led him to that point – in the Solitract’s realm he continues to protest until it violently expels him, but in the story’s final minutes he too is reconciled, with the daughter he lied to and abandoned.

Clearly Erik has been affected by grief, but the calculation involved in his elaborate deception of Hanne cannot be the work of a man unhinged. It is clear, too, that he has not considered bringing Hanne through the mirror to join him, reuniting her, too, with her dead mother. For all the Doctor and Graham’s claims that Hanne ‘needs’ him, he is evidently a very selfish man, his judgement so impaired he is scarcely fit to resume her guardianship. The rapidity with which the other characters forgive him, despite his apparent lack of remorse, is one of several ways in which the detail of the script seems not to match the structure of the story.

The central image of the mirror as a portal between worlds is, of course, a common one in fantasy and supernatural literature, probably most familiar from Lewis Carroll’s Through the Looking Glass (1872). Doctor Who’s most prominent prior use of it, in Warrior’s Gate (1981), draws on director Jean Cocteau’s deployment of the trope in Orphée (1950), his cinema adaptation of the Orpheus myth. Discussing the film, Cocteau noted that ‘we watch ourselves grow old in mirrors. They bring us closer to death,’ which perhaps accounts for why, in It Takes You Away, the dead are to be found there.

A relevant example of the trope is perhaps The Trap (1932), a short story by HP Lovecraft and Henry S Whitehead in which a magician has achieved immortality by hiding in a mirror, and draws others into his realm to become his companions. The magician in question is Danish, and the mirror supposedly the plaything of the Norse god Loki. Other, similarly close parallels may well come to mind.

(The scenes in the mirror universe have obviously been reflected after filming, saving on the expense of completely rearranging the sets to represent the secondary world, but meaning that visible asymmetries in the actors’ faces, hair and jewellery are similarly reversed. The effect might charitably be described as eerie, but may alternatively strike some viewers as cheap.)

That the mirror’s uncanny effects rely on sight, whereas the monster in the woods exists only as sound, is a neat reversal which also makes plot sense of Hanne’s blindness. Her disability means that she believes in the menace outside, while failing to notice that inside her own house. Erik’s deception is ironically inverted when she, unlike him, is able to tell immediately that Trine is a fake, but on the whole the story avoids the ableist cliché of the blind child who perceives things sighted people cannot. In this era of Doctor Who, with its emphasis on representation, her disability is treated as another aspect of human diversity.

One character point which is never discussed, although it is specifically mentioned in the script, is the bandage visible on Hanne’s wrist. In the absence of any other explanation, it is likely to be understood as an indicator that the teenager has responded to the stress of her father’s disappearance with self-harm. It is not clear whether this is a survival from an earlier version of the story where the question was explicitly addressed, or whether (perhaps wisely given that Doctor Who’s audience includes young children) it was only ever implicit.

The first time we see Erik in the otherworld, he and Trine are preparing to eat a sandwich. In context, this may well remind us of the idea in myth and folklore that consuming the food of Fairyland or the Underworld condemns one to remain there. Erik is distracted by the arrival of the Doctor’s party before he can eat, but at this point he has been beyond the mirror for three days, so it seems unlikely that this has been his first meal there. How this relates to the incompatibility of normal matter with Solitract matter – especially in terms of the partially digested food he may take back with him – is mercifully unclear.

The story references food and consumption frequently, beginning with the opening scene, when the Doctor tastes the local soil to learn more about their location. She also refers to ‘the Woolly Rebellion’, a ‘total renegotiation of the sheep/human relationship’ due in 2211, in which we might assume one item on the agenda will be the question of one species eating the other. We later learn that Graham gets ‘cranky when I’m hungry’, and the sandwich he carries to avoid this proves useful in pacifying Hanne – a confirmation of Ribbons’ later suggestion that ‘Luckily anything can be distracted with a little bit of food.’

Ribbons ‘of the seven stomachs’ in particular (a fantastic cameo by Kevin Eldon) speaks repeatedly in terms of eating. He says that ‘tragedy makes me hungry,’ refers to information as ‘tasty’ and ‘delicious’, and speculates about eating both Graham and the Doctor. The Antizone has its own ecosystem, boasting both six-legged rats and flesh moths, and perhaps also the bird we see Ribbons preparing.2

In light of this theme of consumption, it is perhaps odd, and certainly surprising, that the Solitract proves not to be predatory. On the other hand, mirrors traditionally reflect rather than absorbing, and what the Solitract wants is not prey, but an equal.

It Takes You Away is one of only four stories broadcast in 2018 not written by Doctor Who’s 2018-22 showrunner Chris Chibnall. Its scriptwriter was Ed Hime, a playwright who had also been responsible for two episodes of the teen comedy-drama Skins (E4, 2007-13) and would later contribute to the young adult ghostbusting drama Lockwood & Co (Netflix, 2023). His later Doctor Who story, Orphan 55 (2020), has few obvious commonalities with It Takes You Away, but their scripts share an interest in hidden realities and dysfunctional parent-child relationships.

Hime is a passionate environmentalist and a regular protestor with Extinction Rebellion, a concern reflected in Orphan 55. His award-winning radio drama The Incomplete Recorded Works of a Dead Body (Radio 3, 2007)3 deals with themes including cancer, mental instability and suicide, and would not be appropriate for Doctor Who’s family audience. Between them, these works suggest possible analogues for the Solitract’s expulsion from the early cosmos, but interpreting the lonely universe simply as pollution, or a tumour to be cut out, feels reductive. Perhaps a more productive analogy would be the tidying-away from polite discourse of distressing topics like mental health or the climate apocalypse, isolating those who find such matters of overwhelming concern.

More striking perhaps, given that Chibnall is not the credited writer but would undoubtedly have had input into the script, are the commonalities between It Takes You Away and his own defining scripts throughout the remainder of his time as showrunner.

It Takes You Away foreshadows several of the story elements and themes that would become prominent legacies of the era. First, there is an abandoned child, found next to a portal between universes. Secondly, a Black woman, the Doctor’s counterpart, found the other side of a mirror. And finally, the suggestion that the Doctor herself represents and can be identified with the universe.

When It Takes You Away was broadcast, Chibnall’s The Ghost Monument (2018) had already made the series’ first gesture towards the Timeless Child storyline, but the Doctor’s past as a foundling, abandoned like Hanne, presumably by some guardian on the other side of an inter-universal portal, would not be revealed until The Timeless Children (2020). And while Erik’s treatment of Hanne is somewhat less egregious than Tecteun’s medical experiments on her adopted child, both are neglectful and, ultimately, abusive parents – a fact which, oddly, both scripts seem unable to clearly articulate.

Meanwhile, the title of the first story of Chibnall’s showrunnerate, The Woman Who Fell to Earth (2018), refers both to the Doctor and to Grace, who dies as a result of the fall in question, and whose husband and grandson find consolation in their travels with the Doctor. Grace makes other postmortem appearances, variously rationalised, in Whitaker’s first two seasons,4 but gradually cedes her place as a spectral mentor figure to the Fugitive Doctor, an incarnation from and of the Doctor’s distant past, who is introduced in Fugitive of the Judoon (2020) and returns with varying ontological justifications until Whitaker’s final story. The latter is introduced under the name of ‘Ruth’ – an abstract noun, like ‘Grace’ referring to compassion and forgiveness. Both women are reflections of the Doctor, both are somewhat dubious stereotypes of the wise older Black woman, and both are repeatedly associated with mirrors, particularly throughout most of the Fugitive Doctor’s scenes in Once, Upon Time.

In The Battle of Ranskoor Av Kolos (2018), the story that follows It Takes You Away, the Doctor will apparently pray to the universe (‘Universe, provide for me. I'm working really hard to keep you together right now.’) Throughout the era, her habit of personifying the universe is paralleled by the scripts’ tendency to suggest that she herself is such a personification – that, in the final words of Lord Byron’s Darkness (1816), quoted as those of The Haunting of Villa Diodati (2020), ‘She was the universe.’ In It Takes You Away, the Solitract, a universe in its own right, seemingly accepts the Doctor as the representative of the universe she habitually inhabits, and as its equal. The Doctor’s line, ‘’Cos the Solitract doesn’t want a husband, you want a whole universe. Someone who’s seen it all. And that’s me,’ is tantalisingly ambiguous.

Compared with most other periods of Doctor Who, there is little record available of the story development process during Chibnall’s era. Though the texts published at the BBC Writers Room site are useful, they are final versions, their dialogue and stage directions matching what was broadcast.5

In the absence of earlier drafts, and pending comments on the question from Chibnall or Hime, it is impossible to know how much Chibnall contributed to It Takes You Away. These foreshadowings, however, make it difficult to believe that the answer is none at all.6

As a story, It Takes You Away is arguably thrown off its course by two big twists: ‘Actually, there’s no monster outside,’ and ‘Actually, the Solitract is friendly.’ Both of them have the air of editorial complications added to an outline for a more traditional and streamlined Doctor Who story. A tale of a predatory entity luring in its victims through mirrors – perhaps with the help of a beast lurking in the woods – would be a promising proposal in any era of Doctor Who, especially bolstered with a helpful smattering of Nordic folklore.

This theory can only be speculative, of course, and an interview with Chibnall or Hime could shoot it down in a moment. But if these twists were contributions of Chibnall’s to Hime’s original concept, their impact is decidedly mixed. The contortions required to make the monster a fake cast Erik in an irredeemably awful light, when the emotional progress of the story requires him to be redeemed. And the Solitract’s eventual benevolence sits awkwardly with its cruel deceptions of Erik and Graham.

One of the attractions of the Chibnall era is how it sets aside traditional storytelling choices, particularly those that have become clichés in Doctor Who. This doesn’t always work – in many cases, these conventions are there because it is extraordinarily difficult to tell a functional Doctor Who story without them. Opinions are inevitably divided on the hit rate. But when a story from this era fails (as most7 would probably agree Hime’s Orphan 55 does), it does so in ways that are always more interesting than those of the less successful stories in other eras of the 21st century.

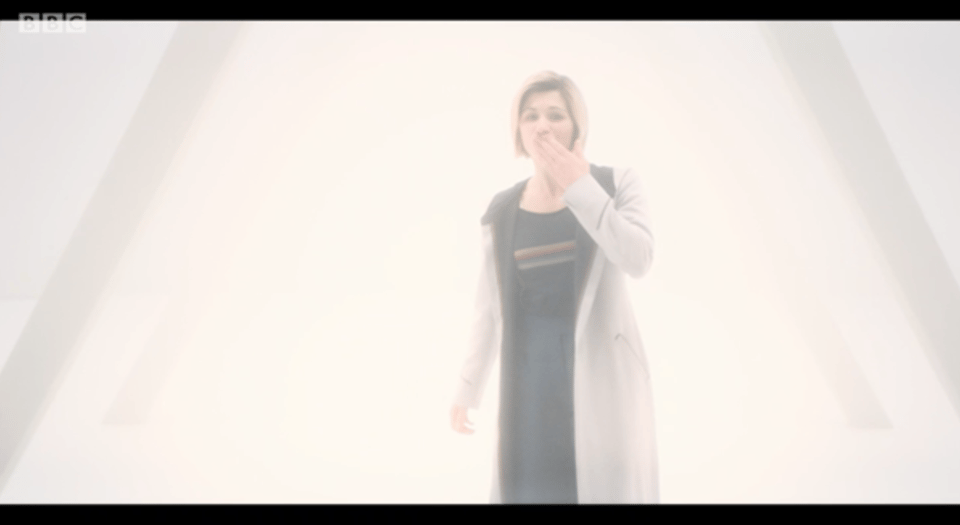

It Takes You Away is a glorious, freewheeling mess, unpredictable and scattershot in its success. But that second twist, that the Solitract is not evil, gifts us the truly glorious climax in which the Doctor befriends, discusses cosmology with, and ultimately parts company with, a universe incarnate as a frog on a chair. The kiss she blows as she leaves, making the moment feel like a farewell between lovers, is one of the quintessential character moments for the Whittaker Doctor.

A simple confrontation with a villain, however much sense it made, would hardly be so memorable.

Admittedly this lesson seems to have been forgotten in the next story, The Battle of Ranskoor Av Kolos, when Graham reencounters Grace’s killer and against Ryan’s advice becomes bent on murderous revenge.

The obvious assumption, given Ribbons’ fondness for trade and the fact that Erik has pheasants in his shed, would be that Erik exchanged one of these for safe passage, but the script says otherwise, referring to it as a ‘large DEAD ALIEN BIRD’ (p18).

The radio play’s script can be read at https://www.bbc.co.uk/writers/scripts/radio-drama/the-incomplete-recorded-works-of-a-dead-body.

As a figment of Graham’s imagination in Arachnids in the UK (2018), in nightmares in Can You Hear Me? and apparently as a presence looking on from Heaven in Revolution of the Daleks (both 2020).

https://www.bbc.co.uk/writers/scripts/whoniverse/doctor-who/series-11-2018. The script of It Takes You Away nevertheless contains some uncorrected errors, including the fun typo ‘frody’ for ‘frog’ (p49).

Alternatively, given that It Takes You Away was made in the first production block of the era, Chibnall might have taken inspiration, knowingly or otherwise, from Hime’s writing.

A “most” that does not include your editor!