Gridlock - “God Knows I Want to Break Free…”

It's a guest post this week, as the brilliant Philip Purser-Hallard offers his thoughts on the magnificent Gridlock to celebrate its (gosh) 17th birthday. Yes, if Gridlock was a person, it would have been allowed to get married for a whole year. Possibly even to a cat.

“God Knows I Want to Break Free…”

Perhaps the first thing to say about Gridlock, the 2007 story in which David Tennant’s Doctor liberates an entire population, including some kittens, from a decades-long traffic jam that they’ve been stuck in for their own good following an apocalypse, is that it’s the third in a trilogy.

Perhaps the second thing to say is that, in many ways, it isn’t.

Gridlock is indisputably a sequel to New Earth (2006), set in the same city on the titular planet and redeeming that story’s villainous henchcat, Novice Hame. Similarly, New Earth was a sequel to The End of the World (2005), following the Earth’s destruction in that story with humanity’s adoption of a new homeworld, and reintroducing the ninth Doctor’s antagonist Lady Cassandra, whose life story it ties off in a satisfying knot.

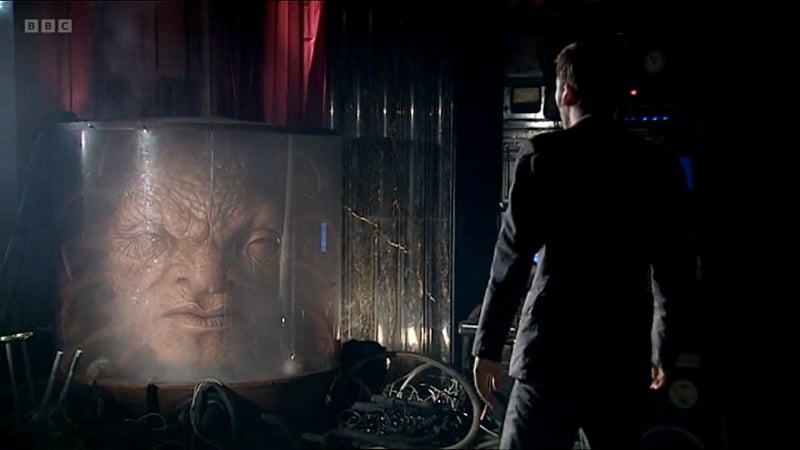

However, Gridlock has little in common with The End of the World, beyond being set in roughly the same far-future time period. Given that both the Eccleston Doctor and Rose have moved on in the meantime, the sole element common to all three stories (other than intrinsic parts of the Doctor Who formula) is the Face of Boe, a large prop barely qualifying as a character, who until the end of New Earth was never heard to speak and was effectively part of the weird far-future scenery.

That said, the Face of Boe may in fact have more agency than it would appear, bodiless as he is and confined to a tanklike life-support system. According to Cassandra it was the Face who convened the party on Platform One, and he also sent the message summoning the Doctor in New Earth. The actions he has taken as part of Gridlock’s backstory to preserve some, at least, of the inhabitants of New New York means that the Face of Boe is, in different ways, responsible for instigating the events of all three stories.

In another sense, the Doctor may bear some responsibility. While no-one comments on the fact, it has to be noted that the human experiments of Hame and the other Sisters of Plenitude, which he closed down in New Earth, were aimed at curing all human disease, and that the disaster that Gridlock reveals wiped out the population of the Overcity a few years later was an airborne virus. Though impeccable in terms of medical ethics, there is surely a chance that the Doctor’s actions in New Earth deprived New New York of its ability to respond to the plague.

Regardless, from his wordless introduction the Face of Boe is elevated here into the Doctor’s "old friend", practically deified by Novice Hame, who sacrifices himself to save New New York and dispenses prophetic wisdom before dying. It might feel rather similar if the ginger cat who Rose petted in Fear Her (2006) had returned, loudly claiming to be the revered ancestor of Brannigan, Hame and all the cats in the kingdom.

For Gridlock, New New York mostly acts as an established setting, a handy backdrop for a parable about humanity’s docile submission to the systems that enslave us. There is an echo of the previous stories’ motif of a search for a new home, as on a personal scale this is why many citizens have entered the motorway, but in their case the quest is a trap and their release returns them to the city where they began. Other ideas we might identify as common across all three stories are perennial concerns either of Doctor Who (e.g. the privilege of the elite, the compromising of bodily autonomy) or of Davies (which we will come to later). There is no sense in Gridlock of concluding a three-part story begun in The End of the World, and it would have been quite unsurprising if the 2008 season had included a return to the era featuring some of the same characters.[1]

More important, perhaps, is Gridlock’s function within the structure of showrunner / writer Russell T Davies’ third series of Doctor Who. Davies’ series tend to have a crystalline symmetry, reflected about the central story, and this is particularly visible in the third and third-from-last stories of each. In 2005, The Unquiet Dead and Boom Town dealt with the attempts of aliens to assimilate in Cardiff, while in 2006 School Reunion and Fear Her saw aliens making use of contemporary children, giving them extraordinary abilities.

2007 is perhaps the clearest example of the third story reflecting the penultimate one. Both Gridlock and Utopia are set in distant, post-apocalyptic futures. Both reintroduce an ‘old friend’ who first appeared in the 2005 season – indeed, if the throwaway comment in Last of the Time Lords linking Captain Jack to the Face of Boe is to be believed, they’re the same old friend. Both deal with social stagnation and the failure of utopian aspirations. And, of course, the Face’s revelation in Gridlock that the Doctor is ‘not alone’ is paid off (and with an explicit callback) in the Master’s return in Utopia.

This also means that both stories reintroduce a decades-old enemy. Because Gridlock is additionally an instalment in an (at the time it was made) 44-year-long epic, which sees the Doctor speaking of his homeworld in terms (orange skies, silver trees) that were established as early as 1964's A Desperate Venture (The Sensorites episode 6).

In the first year of Davies’ revival, focused as it was on establishing Doctor Who’s future, had made few references to its past beyond the necessity of resurrecting the Daleks, but it had become increasingly bold since 2005. The Cybermen, the Master, Sarah Jane Smith and K-9 would all have been all widely remembered among the older audience of the revived series, but the denizens of the motorway’s murkiest depths represent a more repressed memory.

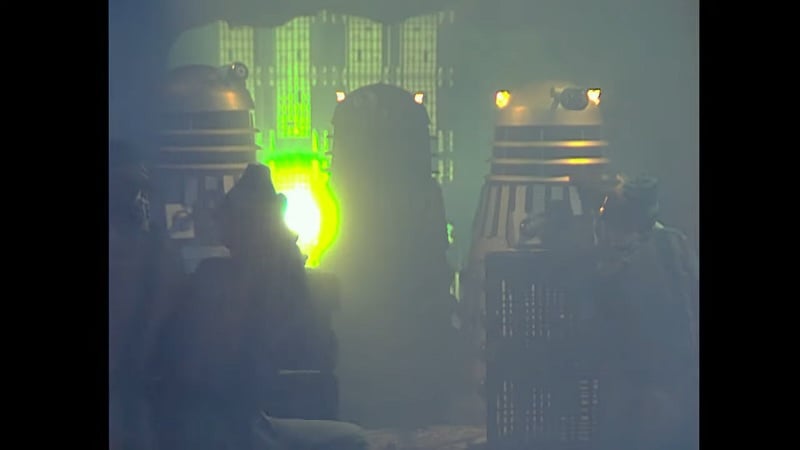

In 2024 we can turn on our TV, or any other device with access to BBC iPlayer, and watch an animated reconstruction of all four episodes of The Macra Terror (1967). But, in 2007, this 40-year-old story was one that even most Doctor Who fans would only have been aware of as one title on the list of ‘missing’ stories deleted in the 20th century by the BBC.[2] The Return of the Macra would never have been a crowd-pleasing phenomenon on the level of the Daleks or the Master, nor even of the Zygons, Sea Devils and Toymaker in more recent stories.

The second Doctor’s monstrous antagonists represent an equally primordial past for the characters in the story – "billions of years ago", according to the Doctor – and accordingly these "devolved" specimens bear minimal resemblance to their ancestors. They remain giant crabs with glowing eyes that "feed off gas", but are redesigned in appearance, vastly larger and apparently non-sentient. Where their predecessors deliberately hypnotised and enslaved humans in order to mine the nutrients they needed, these Macra are exploiting an ecological niche that they had no pincer in creating.

While giant crabs in the bowels of the motorway somewhat recall the legends of giant alligators in the sewers of the original New York, their story function is an incidental one – merely justifying why the motorway’s depths are perilous – and their defeat, if it happens at all, is left implicit. Their reliance on gases humans cannot breathe, extrapolated here to include exhaust fumes, may mean that they cannot survive once the motorway is opened, but this is not clear. After the Doctor leaves, the New New Yorkers may eradicate them as pests, or humanely relocate them, or boil up an enormous bisque. The story shows no interest in the question.

Yet, for all the Macra’s minimal plot role, their presence bears strongly on Gridlock’s themes. What they did in The Macra Terror – brainwashing the populace of the unnamed human colony into compliance, partly through media appearances by a confected figurehead – the citizens of New New York have done to themselves. Furthermore, they reinforce the story’s intense interest in disease and medical issues.

The Macra may resemble crabs, but in episode 4 of The Macra Terror they are described as "like a disease", with the words "germs", "bacteria" and "parasites" all being applied to them. ("Crabs", of course, can also be a term for parasitic lice, while the astrological sign of the crab shares its name with cancer. The name "Macra" itself resembles "microbe".) New Earth was set in a hospital, and Gridlock has similar medical anxieties, navigating a somewhat wobbly pathway between the Macra infestation, the mood-altering substances (referred to simply as "moods") peddled by the residents of Pharmacy Town, the lethal pandemic "virus" into which the mood Bliss somehow mutated [3] and the image of the Face of Boe, reliant on his nurse and his life-support systems.

Thus, oddly perhaps, the Macra bring us to another context in which Gridlock may be read – that of Russell T Davies’ TV scriptwriting oeuvre as a whole.

Reflecting in The Guardian in 2021 on It’s a Sin (Channel 4, 2021), his historical drama of the AIDS crisis, Davies suggested that, prior to this, the impact of the epidemic on the gay community in the late 20th century had rarely been apparent in his work. However, he said, it had been "Rising up. Bleeding through the page […] tick[ing] away in the background," in works such as Queer as Folk (Channel 4, 1999-2000).

Davies makes a specific connection with the death of Vince and Stuart’s friend Phil in Queer as Folk following a one-night stand:

"It’s caused by an overdose, but the man he hooks up with is called Harvey. I said to the producer, Nicola Shindler, 'Harvey? D’you get it? Har-vee, like HIV.” She said, “Don’t be so pretentious. Never tell anyone that.'" [4]

Later in the series, Stuart narrowly escapes his own encounter with Harvey, with the implication that the symbolism would have killed him too.

Here then, eight years before Gridlock, is a similar conflation of mood-altering drugs, consumed in a hedonistic environment, with an inescapable deadly disease. And 14 years afterwards, in It’s a Sin, early AIDS patients like Henry and Colin are shown isolated behind glass, tended at a distance by nurses while their bodies degenerate, and eventually facing a lingering death. In this light, the identification of the Face of Boe, lonely survivor of his people, with gay icon Captain Jack, suddenly makes a kind of horrible sense.

Also, in this context, the deployment of the Macra looks uncannily like the showboating appearance of the Daleks in It’s a Sin. Although the fictional episode of Doctor Who in which the actor protagonist Ritchie appears alongside the Doctor’s archetypal enemies is notionally broadcast in 1988, the setup recalls not that year’s Remembrance of the Daleks but of Resurrection of the Daleks (1984), with its imagery of facially disfiguring bioweapons and fascist aliens passing as London police officers. The scene concludes with a makeup artist commenting on what we know to be Ritchie’s AIDS-related skin condition, and the episode as a whole culminates in a confrontation between AIDS activists and the police.

Here – as in Stuart’s present to fanboy Vince of a working K-9 replica in Queer as Folk, recalling the fourth Doctor’s parting gifts to various of his companions – Davies is drawing on the imagery of Doctor Who for a dual purpose. For the ordinary viewer with a lay knowledge of the series, there is fun in the familiarity, while the scene fulfils its ostensible purpose of emphasising that Ritchie is a moderately successful jobbing actor. For those as steeped as Davies in Who lore, the parallels convey a deeper meaning. Gridlock’s Macra, whose significance would only be apparent to that subset of the dedicated Who audience who knew the mythos in depth, represent a similar signal, broadcast on a narrower band.

It is tempting to see Davies’ interest in apocalypses and dystopias, visible not only throughout his Doctor Who work but in The Second Coming (ITV, 2003) and Years and Years (BBC, 2019) as being inspired by the same grim experience of living through the crisis that destroyed so many of his friends and peers.

The word "apocalypse" (echoed, perhaps, in the name "Sally Calypso") originally meant a revelation, and the name "New Earth" might bring to mind St John’s vision in the biblical book of that name, of a renewed creation arising from the ashes of Armageddon. Davies, who originally cast as the Doctor the same actor who played the returning Son of God in The Second Coming, has portrayed the character messianically from the moment in Rose (2005) when he appeared haloed by the London Eye.

Accordingly, the 10th Doctor’s liberation of those trapped in the motorway recalls the Christian legend of the Harrowing of Hell, in which Jesus, between his death and resurrection, descends in spirit to the region of the netherworld where the virtuous dead have been kept in anticipation of redemption, and frees them to ascend to Heaven. The Doctor will not become incarnate as a human until Human Nature / The Family of Blood, later in 2007, but chronology aside, it tracks.

Perhaps Davies’ most perennial preoccupation, though, played out in multiple variations across his TV drama, is the need for the individual to break out of the rigid constraints imposed by society and tradition, and instead to construct a new community with others of like mind. Some of his works, like Casanova (2005) and Midnight (2008) show this project failing, but in others, like It’s a Sin and Love & Monsters (2006) it is gloriously successful, even if the mortality of its members limits the lifespan of the whole.

For Davies, such communities are often built through music – the disco and dance music of gay subculture in Queer as Folk and It’s a Sin, or the shared devotion of the members of LINDA to ELO in Love & Monsters (2006) – and in Gridlock this takes the form of the hymns, "The Old Rugged Cross" and "Abide with Me", sung by the commuters as part of the "daily contemplation". The End of the World playfully included "religion" with "weapons" and "teleportation" among the items banned on Platform One, while the goddess-worshipping cat nuns were the villains in New Earth. Gridlock shows a more nuanced understanding of the role of spirituality in building a community.

Gridlock portrays a world in which society has been fractured by a pandemic – split into bubbles each of a handful of people, physically separated and able to communicate only electronically. It is a setting that is queasily familiar to most of us in a way that it was not in 2007. Between them, these microenvironments showcase a bewildering variety of subcultures, some of them not immediately comprehensible to the viewer, and a glorious diversity of human (and, this being Doctor Who, nonhuman) relationships. But all are starving from lack of connection, and conference calls, community singalongs and even videos of kittens can only go so far.

The Face of Boe, the benevolent Godlike figure watching over New New York, whose service has reformed Novice Hame, is just as isolated as anyone else in the City. So, too, is the Doctor, saviour of this world, deprived of his companion Rose and filling the gap with Martha, who is uncomfortably aware that she is a replacement. Both are the last of their kind, and in the Doctor’s case his survivor’s guilt is intense. Again, our view of this motif may be coloured by the recollection that Davies lived through a catastrophe in which friends died.

The climax of the plot is of course the Doctor’s liberation of the commuters from the motorway, but the emotional resolution of the story comes afterwards. Before they leave New Earth, and at Martha’s own insistence, he confides in her about Gallifrey’s apocalypse and the extinction of the Time Lords. This, as it happens, is something Gridlock does have in common with The End of the World, where the Doctor made a similar revelation to Rose. In both stories the Doctor admits that he is alone and, in doing so, becomes less so.

This, too, is a moment when the individual reaches out beyond his isolation and begins to build a new community. It acts as a microcosm of the story as a whole.

Of course, that makes the story as a whole a Macrocosm. Which seems appropriate.

Footnotes

1 - In fact Davies returned to the setting in The Secret of Novice Hame, a prose story webcast during the pandemic of 2020 and later published in Adventures in Lockdown.

2 - Admittedly it was available as a novelisation, a narrated soundtrack and a reconstruction based on still photos, but none of those were likely to fall into the hands of a casual fan of the revived series.

3 - Hame’s account is unclear, but it makes more sense if one assumes that the ‘moods’ normally work through modified viruses, and it was this delivery system that mutated.

4 - ‘Russell T Davies: I Looked Away for Years. Finally, I Have Put AIDS at the Centre of a Drama’, The Guardian, 3 January 2021, https://www.theguardian.com/tv-and-radio/2021/jan/03/russell-t-davies-i-looked-away-for-years-finally-i-have-put-aids-at-the-centre-of-a-drama.

5 - In which Dursley McLinden, an actor referenced by Davies as amongst those real life people Ritchie stands in for, played Sergeant Mike Smith.

If you enjoyed that as much as I did, then Phil's Black Archive volumes on Dark Water, Midnight, The Haunting of Vila Diodati and Battlefield are all available as ebooks and paperbacks by hitting the links on their titles. Go get 'em.