Delta and the Bannerman

"Here's to the Future. Love is the answer"

In both the Doctor Who Magazine and Doctor Who Appreciation Society polls of the 1987 series of Doctor Who, each story was deemed an improvement on the previous one. Dragonfire won both, with Delta and the Bannermen second, Paradise Towers third and Time and the Rani fourth. At the time, that was taken as an indication of the “bedding-in” of new script editor Andrew Cartmel’s approach, although no one quite seemed to appreciate just how unreasonable the circumstances in which he and his boss, producer John Nathan-Turner had to put together the series were.

Nearly forty years later, little had changed. By DWM #592 Paradise Towers had sneaked above Delta and the Bannermen, but that was all. That seems right to me, but it always did. I like Delta and the Bannermen, but not as much as the stories either side of it. Yet I have a friend who considers this to be literally the single worst Doctor Who story ever made, and another who’d put it in their top ten of the twentieth century show. (Finding a third way between those positions, my wife considers it the most successful serial, overall, of the season, and the season itself to be an improvement on the previous two, but not as good as the next one.)

I think Delta can provoke such strong reactions because again, and like Paradise Towers, it’s not much like any Doctor Who serial before it. More, the ways in which it’s like earlier Doctor Who do not make it like then recent Doctor Who.

Yes, it’s a “pseudo historical”, in Doctor Who fan argot this is a story set in the past, but which shows that past being threatened by aliens from outer space or the future, but the “history in the making” of Delta and Bannermen is that of living memory. The closest Doctor Who had really come to this was in the (ultimately revealed to be ersatz) Great War trenches of The War Games (1969). But they were fifty or so years in the past when that story was made. Delta and the Bannermen’s 1959, presented to the television audience of 1987, was barely half that amount of time. It was within the childhood memories of people barely into their own thirties. An equivalent story made today would be set during the Battle of Britpop.

I make that comparison not just to provoke howls of horror from my contemporaries, but also because one of the other ways in which Delta And The Bannermen is new is that it’s the first Doctor Who story to use significant amounts of archive popular music to soundtrack itself. This was a trend in film and television underway in 1987 but not as ubiquitous as it would be five years later. It also makes sense. The way to evoke earlier parts of the media age is through music, and not just the rock and pop (e.g. Rock Around the Clock, Singing the Blues, most memorably Why Do Fools Fall in Love?) but also the kind of background light music and radio themes, Calling All Workers or Devil’s Gallop or Children’s Favourites, that would, well, be recognised as artefacts of childhood by people in their thirties, who were also the likeliest demographic to be the parents of the child section of Doctor Who’s audience.

Except, of course, that archive rock is mostly not archive. They were re-recorded by Doctor Who’s three-on-the-bounce composer Keff McCulloch as part of a one-off group that included his wife and her sister (both professional singers). This was in part because much of the music would be performed live in the story. Diegetically, it’s not the records, it’s people enthusiastically playing the music from the records themselves while at Shangri-La, the down at heel Welsh holiday camp at which much of the story is set.

I say “in part”, though, because it also helped minimise music licensing costs, which can easily escalate, and this is a ridiculously ambitious production for a series that, as I’ve said before and will have occasion to bring up again, an internal BBC report in 1989 decided was made on a literally impossible budget, concluding that Doctor Who’s 1986-89 allocation of 14 episodes was insufficiently long to practically spread its costs across a season.

That admirable, if pyrrhic, production ambition shows itself in clever uses of in-camera sets and early digital post production tricks to show characters running into huge spaceships onscreen, as well as the decision to shoot the serial almost entirely on location to give a sense of space and scale. Where the production fails it’s in elements like the staging of action, and on set explosions, that simply couldn’t be restaged on the show’s schedule.

What the summer location work offers is blue skies and bounce, optimism appropriate to the “never had it so good” end of the 1950s. That setting is also itself an appropriate vessel into which to pour such 1950s elements as the earliest artificial satellites, the Cold War, Hugh Lloyd, Stubby Kaye and the “classic” SF tropes (such as a fugitive alien princess with whom a human falls in love) which Delta imports not ironically, but both knowingly and sincerely.

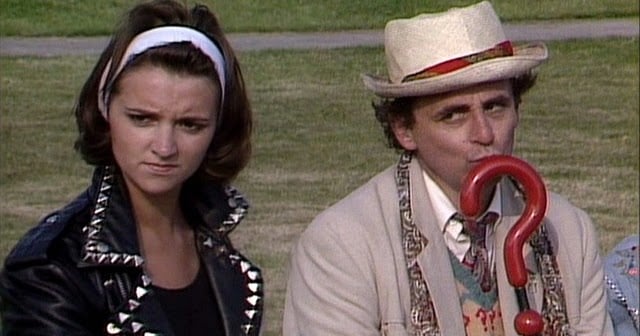

That sincerity is important in other ways too. Ray (Rachel Griffiths) considered as a future companion, but then passed over in favour of Sophie Aldred’s more contemporary Ace, is sweet and subtle, and it’s her performance’s lack of side, its unblinking honesty, that enables that. This is true also of Richard Davies’ Burton Burton, the camp leader at Shangri-La. One of the things the Cartmel era is very, very good at is surprising but authentic feeling character moments, and we have a great example here as, when arguing in front of the Doctor, Burton and Ray slip into Welsh in their anxiety to be understood by each other.

Burton has other great moments. He initially presents as a pure comedy figure, in line with some of Davies’ other screen roles (and his delivery of “You are not the Happy Hearts Holiday Club from Bolton but are in fact spacemen in fear of an attack from some other spacemen?” is magnificent) but he also insists on staying to help fight the Bannermen off, while protectively sending his staff away. At one point he waves an antique sword, saying “I haven’t used it in over forty years”, and while it’s a funny moment, it’s one you suddenly realise is him talking about active service in the Great War, and just before he quietly mutters “shot and shell” as the conversation moves on.

Burton’s boldness is later demonstrated as genuine bravery when later in the same episode he rushes to save Mel’s life from Gavrok, risking his own in the process. Especially considering that she’s a young woman with whom he’s exchanged a handful of casual words. This Major is not, unlike the one in Fawlty Towers, a Blimp or Martinet. He’s an ordinary person, with foibles and eccentricities and contrasting character traits. One of many more to come in the Cartmel era.

The tour party that takes aliens to 1950s Earth is called “Nostalgia Trips”, but the script is careful not to be too rose-tinted. Mel mock-despairs of the holiday camp’s dilapidated state, and other aspects of it, such as regimented meal times, the “list of rules and regulations behind the door” and campers being communally awoken by a song played over the personal address system, evoke another time, but not exactly fondly. “This is real fifties!” says the Doctor at one point. Not quite, no. But the portrayal is at least not simply glowing.

1950s nostalgia was very much a thing in 1987. Amongst the twenty UK #1 singles of that year were reissues of Reet Petite (1957) and Stand By Me (1961) and a cover of La Bamba (1958), the latter two connected to films of the same titles about the period. These are all songs you could reasonably expect to hear on the radio in a story set (approximately) both when Delta is set and when it was made.

This ties into what I was saying recently about the 1987 series of Doctor Who being instinctively contemporary. Even in its “pseudo historicals”. Because while this is the 1950s, it’s the 1950s as familiar to television viewers of 1987 from the sitcom Hi-De-Hi! (1980-88). Equally, the next story will take us to a freezer centre. Sure, it's a space freezer centre, but like the tatty holiday camp or the high rise block, it’s an artefact of the Britain in which Doctor Who was being made. A Britain which is now longer ago than that in which it was set was then.

Because this story is now a historical take on the historical, and like a television or film adaptation where the adapter seems as present as the original author, Delta and the Bannermen is now as much 1987 as 1959; when in 1987 its 1987ness was neutral. The synthesised noises in the recreated pop are obvious now in a way they weren’t, or weren't to me and my contemporaries, on transmission. That this is a 1950s on SD video, not film, seems odder now than when there was a comedy series set in the same period and shot in the same way airing on the same channel in the same year. It’s a historical squared, but at the time? At the time it pointed to the show’s future.

If we take the old definition of a comedy as a play that ends with a marriage, then it’s suitable that Delta and the Bannermen kind of is and kind of does, and it continues on from Paradise Towers in being a comedy about serious things. But there there was satire and sacrifice and a bittersweet ending. Delta and the Bannerman has a climax in which Doctor Who arranges a clever trap that frustrates and temporarily disables, not kills, and its chief villain Gavrok dies as a result of an alternative, murderous trap he set himself. His mercenary followers are tied up and sent for trial. That faith in the rule of law to settle things, rather than redemptive violence, is very 1950s too.

This is the first Doctor Who story in a long time to end not just with a weak joke but (and despite the conflict within it) happily and unambiguously upbeat. Hopeful. To some that might seem “soft” in some nebulous way. I am sure Eric Saward would not have approved. But here it feels a sign of renewed confidence and vigour.

“Happy days are here again.”