“And if you go chasing robots..."

This is a full length and free to read version of a post written and sent to paid subscribers a while back. You may have read the first third back then, before the paywall. But it’s now all there, even if the Mad Hatter isn’t .

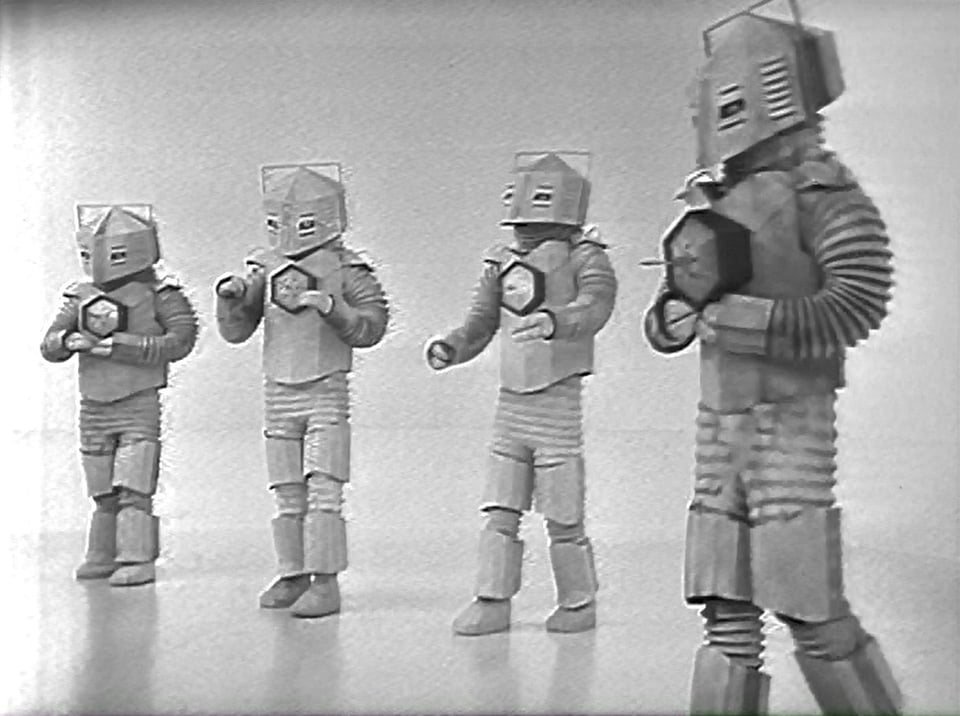

The TARDIS has been taken out of time and space altogether. It sits in a white void, one seemingly unpopulated except for by silent, insistent White Robots. Pressed by Zoe (Wendy Padbury) as to where they’ve ended up, Patrick Troughton’s Doctor Who notes, not without fear, “We’re nowhere. It's as simple as that.”

Those White Robots were a recycled monster, costumes constructed for an episode of the BBC SF anthology Out of the Unknown (1965-71). It was called The Prophet, and was adapted from Isaac Asimov’s short story Reason. In both, the experimental robot QT1, designed for working on an orbiting satellite, questions how mere humans could have created itself and its brethren. It concludes that they could not have. That machines must have been made by other machines. QT1 then decides that the station’s power generator is God, and quickly becomes hailed as its, well, check the episode’s well-it’s-catchier-than-the-story’s title. The Prophet was shown on 1st January 1967 on BBC Two, and then repeated on 27th May of the same year on BBC One.

In Spring 1968 the Doctor Who production office found itself in crisis. Crises, often self-created ones, weren’t uncommon under producer Peter Bryant, but this crisis had multiple repercussions, just one of which we’re going to deal with here. The Dominators, written by regular Doctor Who writers Mervyn Haisman and Henry Lincoln, had been cut from six episodes to five late in the day. This not only incurred the authors’ wrath, it left the series an episode short.

To fix this, Bryant and his script editor Derrick Sherwin decided to add an episode onto the front of the final serial of the current production “season”, The Mind Robber. This four part story was being written by Crossroads co-creator Peter Ling. It was inspired by Ling’s observations his soap opera’s audience, who would send letters, and even birthday and Christmas cards to the set. But they were addressed to the characters rather than the actors who played them. More, when the cast of Crossroads encountered the series’ fans in the street they would, they reported, often talked to as though they were the characters, being commiserated on onscreen tragedies and passed information the viewers knew but their characters did not.

Ling’s story, originally commissioned as Manpower1 was set in a world where the TARDIS crew encountered both mythical and explicitly fictional characters; one where the Doctor and his companions Zoe and Jamie (Frazer Hines) would find themselves existentially threatened by having their own reality stripped from them. Of becoming fictional themselves.

Sherwin wrote the new first episode for this serial himself. This saved time and money. But the episode would still need to be made, requiring costumes, props and sets, all of which had costs. Right at the end of Doctor Who’s longest ever production block, the money just wasn’t there. Sherwin’s response was to set The Mind Robber’s new Episode 1 entirely in white void, that “nowhere” between reality and the world of the rest of the serial. The episode would involve no actors except the series’ regular cast of three2, and the monsters would be those robots left over from Out of the Unknown.

The forward plot motion of The Mind Robber seems to show the characters walking through the pages of some kind of children’s annual, of the specific kind popular in the interwar years, before the market for such books became dominated by licensed characters. There are pages of proverbs and puzzles. The unicorn, frozen against its black background seems like a full page illustration, a magical animal sketched in in charcoal, or appearing on a dramatic photograph plate. We have a maze game of the kind common in annuals into the present century, but in this case inspired by the classical myths of Theseus and the Minotaur and the Medusa. Sections from the classic Gulliver’s Travels3 are interspersed throughout. Which makes sense for a book not written for children, but frequently excerpted or adapted to become children’s fiction. Sherwin’s ex post facto first episode, with its white void, seems to add blank pages to the front of the book they’re traversing, extending the serial in a way entirely in keeping with the rest of it.

It’s a measure of how Doctor Who dominates the posterity of anyone and anything who comes into contact with it professionally that those White Robots are available as a Doctor Who collectable in a world where few remember the existence of Out of the Unknown, and despite its relatively recent release as a (sadly already deleted) BFI DVD box set. That’s partially because The Prophet is not one of the known-to-be-extant episodes of Out of the Unknown, and thus you couldn’t see it even when you could buy much of the series. But only partially. There is more than one kind of being forgotten.

A case in point; not long ago, television researcher David Brunt4 dug up a photograph from The Metal Martyr, an episode of Thirty-Minute Theatre (1965-73) transmitted on 27th December 1967 - and look what it contains.

Thirty Minute Theatre is a genuinely obscure BBC anthology drama series, denied even a deleted BFI DVD box set5 despite being the first UK drama series to be transmitted in colour. As a series of half hour standalone plays, Thirty Minute Theatre ate up material at an astonishing rate. Sadly, of its 291 episodes only around 50 survive and The Metal Martyr is not one of them. Hence no one, seemingly, knowing of this intermediate stage between The Prophet and The Mind Robber before Brunt discovered the picture above.

Significantly, The Metal Martyr was produced by George Spenton-Foster, who had also been Associate Producer of The Prophet. The Metal Martyr’s script was by Derrick Sherwin, written almost immediately before he formally became Doctor Who’s Script Editor. We have causal links in a chain here.

This new image from The Metal Martyr, and just like extant photographs for The Prophet, shows that the White Robots weren’t originally white. Possibly, they’re Blue Robots. For their Doctor Who appearance they were repainted, presumably to allow them to blend into and emerge sinisterly from the white void in which they would be found. Their identifying numbers were removed.

Several of the “fictional characters” encountered in The Mind Robber are no such thing. Cyrano De Bergerac,6 Blackbeard the Pirate7 and the Musketeer d'Artagnan8 are all real people who are now better known through fictional avatars; it seems absurd to suggest - as some have - that this is accidental on Ling’s part. That he, by mistake, populated his story about the terrifying threat of becoming fictional with versions of real people whose posterity has been obscured by fictional representations of them. Because this is surely the closest equivalent the real world has to what Doctor Who’s Master Brain of the Land of Fiction threatens to do?

So maybe, just maybe, these robots aren’t just costumes reused from The Prophet and The Metal Martyr, they are those robots, living in the Land of Fiction like Gulliver and the Princess Rapunzel. But then they’re the wrong colour. So perhaps they have been turned white by the process of being made fictional, exactly as Jamie and Zoe are on more than one occasion in The Mind Robber. Their numbers have gone along with the rest of their individuality. Somehow the absorption of these third hand props into the wider cultural edifice of Doctor Who reflects, and in a way that cannot possibly be deliberate, one of the major concepts behind the story in which they appear.

The White Robots rarely appear after the first episode of The Mind Robber, supplanted by the giant Tin Soldiers asked for by Ling’s original scripts. Although they do return to play a key role in the story’s climax. It is horribly tempting to see, in their nearly homophonic names, their shared role in beckoning the protagonists and their audience into a dream world, and their return to play a role in the drama’s close, a kind of kinship between these White Robots and the White Rabbit from Alice in Wonderland9

Because, due to how different it is to much of the rest of the series, The Mind Robber does seem to have have been intended to framed as a kind of dream episode. This is the implication of the script for the Episode 1 of The Invasion, the next story made. There the Doctor wakes up in the chair in which he slept during The Mind Robber Episode 1.

Whether the Doctor is awaking at the end of Episode 1 of The Mind Robber or at some point during it is unclear. The TARDIS has escaped Dulkis, so some of the episode happened. As in Alice it uncertain when the dream begins, and the White Robot / Rabbit is there at that liminal moment.

It's also because of this dream element that it has been ingeniously suggested that the giant Tin Soldiers and the White Robots represent Jamie and Zoe’s unconscious fears of the Cybermen and the Quarks respectively.10 Alternatively, and perhaps even more attractively, both new monsters are the Cybermen; the Tin Soldiers are them as Jamie sees them, the White Robots as Zoe does. (Jamie and Zoe being from 1746 and the early twenty first century respectively.)

But, let’s consider the White Robots liminal nature again. At the serial’s climax, the Robots are tricked into opening fire on the Master Brain of the Land of Fiction itself. Their weapons, it seems, damage, perhaps even destroy it. This would suggest that their firepower is real, and so they must be too. That they are a real part of the Land of Fiction. Either that or the dreamer can be destroyed by the dream.

“Well, it no use you’re talking about waking him,” said Tweedledum, “When you’re only one of the things in his dream. You know very well you’re not real.”

There are not quite overt, direct references to Alice in The Mind Robber as seen on television. Ling filled some in when he came to novelise the story in 1986. Zoe is dressed as Alice, and when she is tempted through a door, as in the televised Episode Two, she then falls down a rabbit hole. The book also sees the Doctor, like Alice, sleeping and then waking with his back to a tree.

She looked down at herself and caught her breath. For the silver jumpsuit had gone, and in its place was a long dress of pale blue, with a silk sash at her waist, and a full skirt, puffed out by stiff under-petticoats. She was wearing high buttoned booted and when she put her hand to her head she found a band of ribbon tying back her long hair.

…

So she stepped bravely through the doorway - and at once the for opened up beneath her feet, and she gave as terror as she fell - down . . . down . . . down ... Would the fall never come to an end?Poor Zoe! How could she know that it was only a rabbit hole?

…

Somewhere in the Citadel, the Master hugged himself with delight: “Dear Lewis Carroll,” he murmured.

There might be an Alice in The Mind Robber as transmitted, but if there is, she’s Alice Bastable, one of the ten year old twins who are part of the Bastable brood from The Story of the Treasure Seekers (1899). This has been the assumption of some critics, and it’s a fair one based on the children’s appearance and personalities, but they aren’t named in the credits, the script or even the book.

It’s almost surprising that The Mind Robber doesn’t borrow more overtly from Alice, that its influence is more diffuse. 1966 had seen Jonathan Miller’s rightly acclaimed adaption of the book transmitted for Christmas, and it had been repeated in 1967. A 1966 Disney Time had included clips from the company’s 1951 film version, and the series An Engineer in Wonderland, also transmitted twice in 1966/67, had seen Professor Eric Laithwhaite explain engineering concepts via symbolism and examples from Dodgson’s work. In May 1966 future Doctor Who Richard Hurndall had starred as Dodgson in A Don in Wonderland, which explored the writer’s creativity.

In December 1966 the Home Service gave John Gielgud and Malcolm Muggeridge forty minutes to chat about the book, and BBC Two handed Ravi Shankar the same to talk about his music for Miller’s play. The same month, Stuart Hood took to the Third Programme to talk about Alice as an expressions of the anxieties of childhood.

Even Doctor Who had already been there. The Celestial Toymaker (1966) draws, at least in its transmitted form, noticeably on on Alice, featuring an antagonistic Queen of Hearts - albeit one who at no point cries “Off with their head!” - and a series of nightmarish puzzles with unnavigable, arbitrary rules. Tellingly, this story too threatens the TARDIS crew with the possibility that they might become unreal in some way, and has inhabitants of its dreamworld who seem to once have been real.

The Mind Robber was commissioned in January 1968. Until the 23rd of that month The Beatles’ Hello Goodbye / I Am The Walrus was the UK’s #1 single. Until the 16th the Magical Mystery Tour EP from which the latter, but not the former, was excerpted, nestled snugly behind it at #2.11 It’s a paradox worthy of Carroll that I Am The Walrus should be on both the #1 and #2 selling records, but not “count” for either.

Alice was everywhere. This was, of course, in part because of the centenary of its first great success in 196612. But an easy explanation of prominence does not negate prominence.

In mid-1969, Doctor Who returned Out of the Unknown‘s prop lending favour: The also-missing episode Get Off Of My Cloud featured Daleks as part of a dream of its own. They are seen in a contemporary-set childhood nightmare, before the episode follows the character in adult life in the then future. The Daleks, real in Doctor Who, are fiction in Out of the Unknown.

It was the first time Daleks were seen on television in colour (and the only time in the sixties).13 Responsible for looking after them for Out of the Unknown was their designer Raymond P Cusick, who’d also taken charge of the not-yet-White Robots for The Metal Martyr.

Get Off Of My Cloud was directed by Peter Cregeen. Cregeen never worked on Doctor Who but would, twenty years later, as BBC Head of Drama Series, be the person who quietly axed the twentieth century version of the show. The Queen of Hearts might have approved.

“When the Red King stops dreaming you, where are you then?” Tweedledee retorted contemptuously. “Nowhere.”

This is still the title on the story’s rehearsal scripts.

Patrick Troughton thought this placed unacceptable demands on him and his colleagues, and the episodes’ scripts were trimmed to run short to reflect this. Episode Five is exactly 18m, when Doctor Who was usually expected to fill a 25m slot.

More properly Travels into Several Remote Nations of the World. In Four Parts. By Lemuel Gulliver, First a Surgeon, and then a Captain of Several Ships (1726).

The first of David Brunt’s archive based production diaries for twentieth century Doctor Who can be pre-ordered here. I would encourage you to do so.

A handful of surviving episodes have been made available, e.g those directed by Alan Clarke are included on Dissent & Disruption, the BFI’s DVD and Blu-ray set(s) devoted to Clarke’s BBC television work.

1619–55

Edward Teach, 1680 – 1718

Charles de Batz de Castelmore d'Artagnan, 1611 – 1673

More properly Alice's Adventures in Wonderland (1865), pre-publication Alice's Adventures Under Ground. Often conflated with its sequel Through the Looking-Glass, and What Alice Found There (1871). Hereafter collectively Alice.

E.g in the hugely influential The Doctor Who Discontinuity Guide (1994) by Paul Cornell, Martin Day and Keith Topping.

There is also Jefferson Airplane’s White Rabbit, which I (mis) quote at the top of this piece. But White Rabbit was not only not a single in the UK, it was not even included on the UK version of Surrealistic Pillow, the US album from which it was drawn.

The book was first published in 1965, but not in an edition that could be widely read until the following year.

A cinema advertisement for Walls Sky Ray Lollies’ Doctor Who promotion was made in colour, but only ever shown on television in black and white. Some of Terry Nation’s personally owned Dalek props appeared with him on a colour film insert interview with him and Alan Whicker for A Handful of Horrors: I Don’t Like My Monsters To Have Oedipus Complexes transmitted 27th January 1968.