Napkin Problem 12: Recommendations

Since last, I sat down with Adam and Jerod from The Changelog podcast to discuss Napkin Math! This ended up yielding quite a few new subscribers, welcome everyone!

For today's edition: Have you ever wondered how recommendations work on a site like Amazon or Netflix?

First we need to define similarity/relatedness. There's many ways to do this. We could figure out similarity by having a human label the data for what's relevant when the customer is looking at something else: If you're buying black dress shoes, you might be interested in black shoe polish. But if you've got millions of products, that's a lot of work!

Instead, what most simple recommendation algorithms is based on is what's called "collaborative filtering." We find other users that seem to be similar to you. If we know you've got a big overlap in watched TV shows to another user, perhaps you might like something else that user liked that you haven't watched yet? This recommendation method is much less laborious than a human manually labeling content (in reality, big companies do human labeling and collaborative filtering and other dark magic).

In the example below, User 3 looks similar to User 1, so we can infer that they might like Item D too. In reality, the more columns (items) we can use to compare, the better results.

Based on this, we can design a simple algorithm for powering our

recommendations! With N items and M users, we can create this matrix of M x

N cells shown in the drawing as a two-dimensional array and represent

check-marks by 1 and empty cells by 0. We can loop through each user and

compare with each other user, preferring recommendations from users we have more

check-marks in common with. This is a simplification of cosine similarity

which is typically the simple vector math used to compare similarity between two

vectors. The 'vector' here being the 0s and 1s for each product for the user.

For the purpose of this article, it's not terribly important to understand this

in detail.

How long it take to run this algorithm to find similar users for a million users and a million products?

Each user would have a million bits to represent the columns. That's 10^6 bits

= 125 kB per user. For each user, we'd need to look at every other user: 125

kB/user * 1 million users = 125 Gb. 125 Gb is not completely unreasonably to

hold in memory, and since it's sequential access, even if this was SSD-backed

and not all in memory, it'd still be fast. We can read memory at ~10 Gb/s,

so that's 12.5 seconds to find the most similar user for each user. That's way

too slow to run as part of a web request!

Let's say we precomputed this in the background on a single machine, it'd take

12.5 s/user * 1 million users = 12.5 million seconds ~= 144 days ~= 20 weeks.

That sounds frightening, but this is an 'embarrassingly parallel problem.' It

means we can process User A's recommendations on one machine, User B's on

another, and so on. This is what a batch compute jobs on e.g. Spark would do.

This is really 12.5 million CPU seconds. If we had 3000 cores it'd take us

about an hour and cost us 3000 core * $0.02 core/hour = $60. Most likely these

recommendations would earn us way more than $60, so even this is not too bad!

When people talk about Big Data computations, these are the types of large jobs

they're referring to.

Even on this simple algorithm, there is plenty of room for optimizations. There will be a lot of zeros in such a wide matrix ('sparse'), so we could store vectors of item ids instead. We could quickly skip users if they have fewer 1s than the most similar user we've already matched with. Additionally, matrix operations like this one can be run efficiently on GPU. If I knew more about GPU-programming, I'd do the napkin math on that! On the list for future editions. The good thing is that libraries used to do computations like this usually do these types of optimizations for you.

Cool, so this naive recommendation algorithm is feasible for a first iteration of our recommendation algorithm. We compute the recommendations periodically on a large cluster and shove them into MySQL/Redis/whatever for quick access on our site.

But there's a problem... If I just added a spatula to the cart, don't you want to immediately recommend me other kitchen utensils? Our current algorithm is great for general recommendations, but it fails to be real-time enough to assist a shopping session. We can't wait for the batch job to run again. By that time, we'll already have bought a shower curtain and forgotten to buy a curtain rod since the recommendation didn't surface. Bummer.

What if instead of a big offline computation to figure out user-to-user similarity, we do a big offline computation to compute item-to-item similarity? This is what Amazon did back in 2003 to solve this problem. Today, they likely do something much more advanced.

We could devise a simple item-to-item similarity algorithm that counts for each item the most popular items that customers who bought that item also bought.

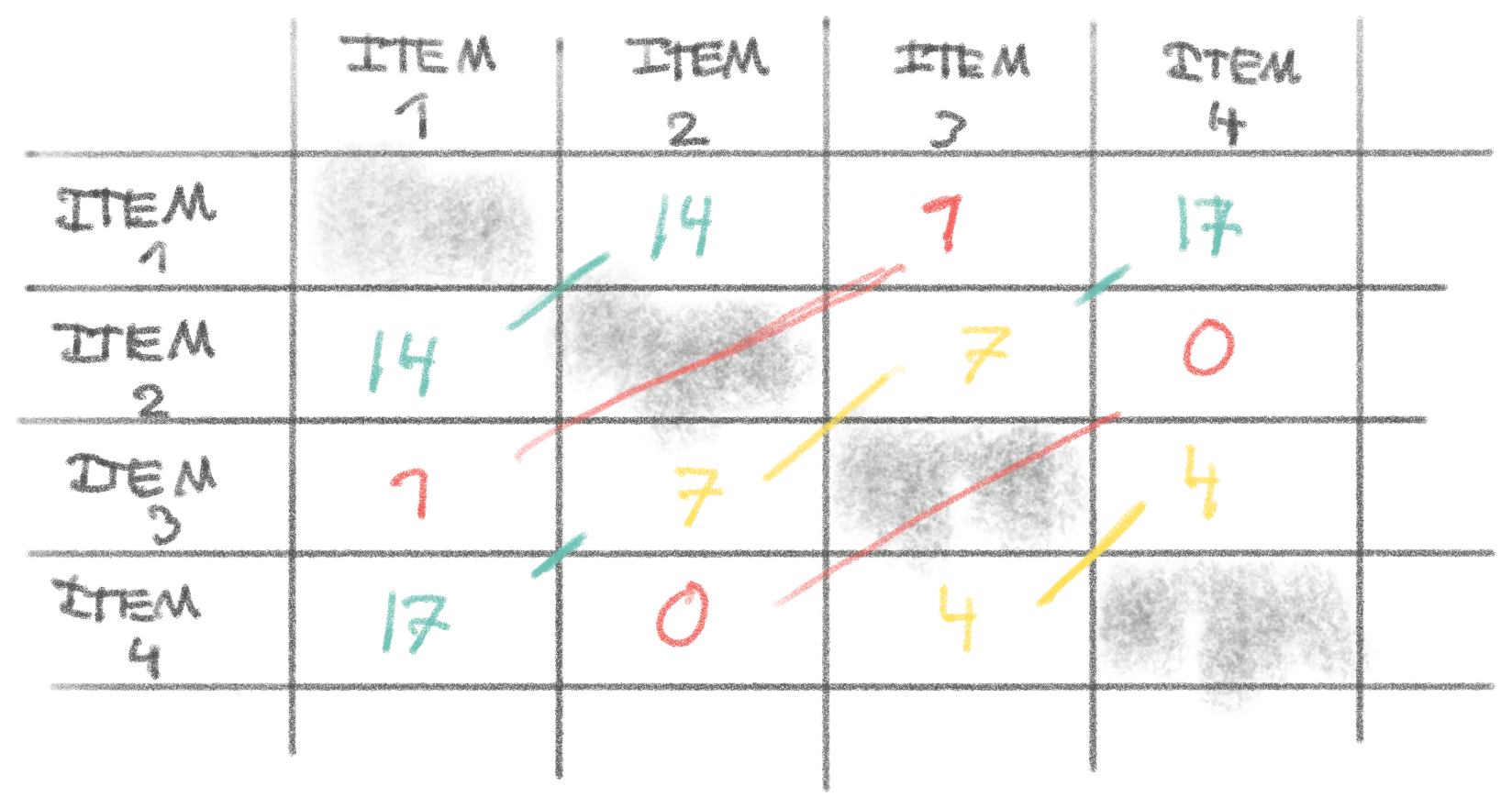

The output of this algorithm would be something like the matrix below. Each cell is the count of customers that bought both items. For example, 17 people bought both item 4 and item 1, which in comparison to others means that it might be a great idea to show people buying item 4 to consider item 1, or vice-versa!

This algorithm has complexity even worse than the previous one, because worst

case we have to look at each item for each item for each customer O(N^2 * M).

In reality, however, most customers haven't bought that many items, which makes

the complexity generally O(NM) like our previous algorithm. This means that,

ballpark, the running time is roughly the same (an hour for $60).

Now we've got a much more versatile computation for recommendations. If we store all these recommendations in a database, we can immediately as part of serving the page tell the user which other products they might like based on the item they're currently viewing, their cart, past orders, and more. The two recommendation algorithms might complement each other. The first is good for home-page, broad recommendations, whereas the item-to-item similarity is good for real-time discovery on e.g. product pages.

My experience with recommendations is quite limited, if you work with these systems and have any corrections, please let me know! A big part of my incentive for writing these posts is to explore and learn for myself. Most articles that talk about recommendations focus on the math involved, you'll easily be able to find those. I wanted here to focus more on the computational aspect and not get lost in the weeds of linear algebra.

P.S. Do you have experience running Apache Beam/Dataflow at scale? Very interested to talk to you.