Linkfest #42: Phytomining, Adversarial Poetry, and Popping A Wheelie for 93 Miles

Hello!

It’s time for "the opposite of doomscrolling” — my next Linkfest, a collection of the most interesting items in science, culture and technology I could find during a complete A-to-Z reading of the entire known Internet.

If you’re a subscriber, thank you! If not, you can sign up here — it’s a Guardian-style, pay-whatevs-you-want affair; the folks who kick in help keep the Linkfest free for everyone else. (Full archive of issues, including this one, is online free here.)

And: Please share this email with anyone who'd enjoy it.

Let’s begin ...

1) 🎨 Aerial embroidery

Behold the lovely embroidered landscapes created by Victoria Rose Richards — each one looks like a textiled vision of the planet as seen from a passing airplane.

As she notes, there’s something fascinating about the geometry of our landscapes: Humans attempt to impose firm Platonic shapes on the fields around us, but their edges are often slightly softened or distorted by the facts on the ground — like hills, trees, waterways, and the like. So it’s geometry, with fuzzier math:

In living in the countryside in a place of natural beauty, I am surrounded by inspiration for my pieces in the endless fields and meadows, lush forests, winding rivers and reaching moorland. I’ve always had an interest for aerial landscapes and use a combination of stitches on felt sheets to recreate them based on the Devon countryside. I particularly enjoy recreating the fields – I love the shapes they naturally form and are made to form by agriculture, seemingly perfectly fitted together yet forced.

She’s got a huge gallery of dozens of these works, sadly all of which appear to be sold. I’d love to get one some day …

2) 🚲 Popping a wheelie for 93 miles

Oscar Delaite, a 19-year-old student in France, just did a bicycle wheelie for 93 miles — a feat that required six and a half hours of riding on one wheel.

The Guiness Book of World Records confirmed that Delaite has pulled off the “Greatest Distance Covered While Performing a Continuous Bicycle Wheelie”, and Jason Gay at the Wall Street Journal has the story (gift link):

Oscar trained for more than a year, 10 to 15 hours a week. His record-breaking set up was quite typical: a Rose commuter bike with a flat bar and slick, 50 millimeter width tires, standard pressure. The only modification was adjusting the seat so Oscar could sit as he attempted the record.

Delaite wore a helmet, a camera strapped to his chest, and a water supply draped around his back. He did not wear fancy cycling shoes—he wore Nike basketball high-tops. Over the six and a half hours, he averaged a speed of 14 miles an hour, which is rather remarkable.

I asked him what he thought about during the attempt. Could he daydream? Could he zone out and listen to the entire Dylan catalog? Terrible podcasts?

“I had to be focused,” he said. “I checked the times, the number of laps. The last hours are really, really intense. If I make a mistake, I can’t restart at 100 kilometers.”

Apparently his arms and legs felt fine; his butt, however, was pretty sore.

I’m impressed. And I’m familiar with bike stunts — I cycled across the entire United States, from NYC to the Pacific, two years ago! (Annnnd my book about it arrives spring of 2027; you will be hearing much more about this from me in the year to come.) I’ve done lots of rides of 93 miles or more … but I used both my wheels, which now feels like cheating or something? This kid is metal.

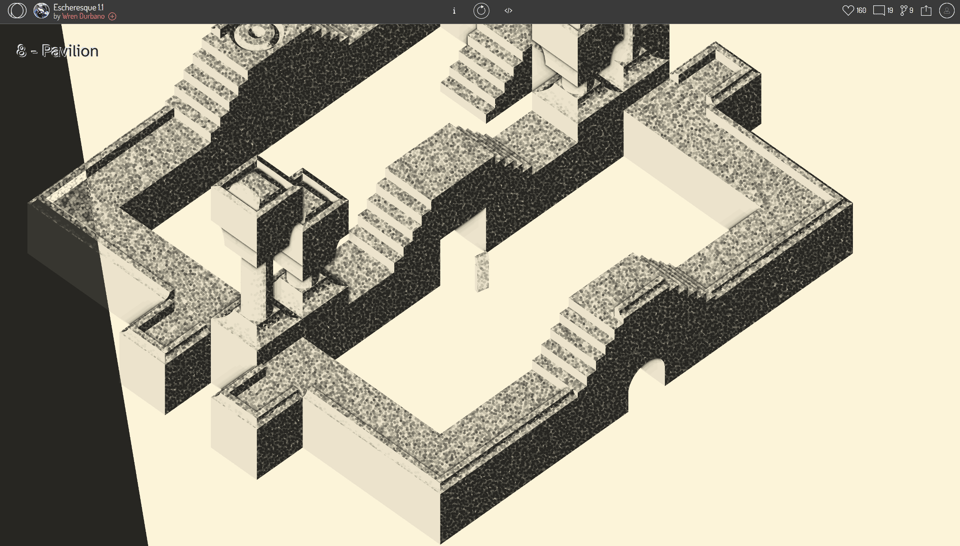

3) 👾 “Escheresque”, the game

The digital artist Wren Durbano has created “Escheresque”, a trippy little browser game where you walk around a faux-3D isometric world composed of platforms, stairs and tunnels — all done in a style vaguely reminiscent of Escher. When you hit the spacebar the scene swaps between dark and light modes, each one slightly changing the configuration of the scene … and allowing you to navigate through the puzzle levels.

It’s not terribly hard, so I found it kind of soothing to play.

4) 🧮 Weirdest Excel functions

Amir Bohloohi went digging around inside Excel and discovered that it includes some very cool — if extremely weird and specific — functions.

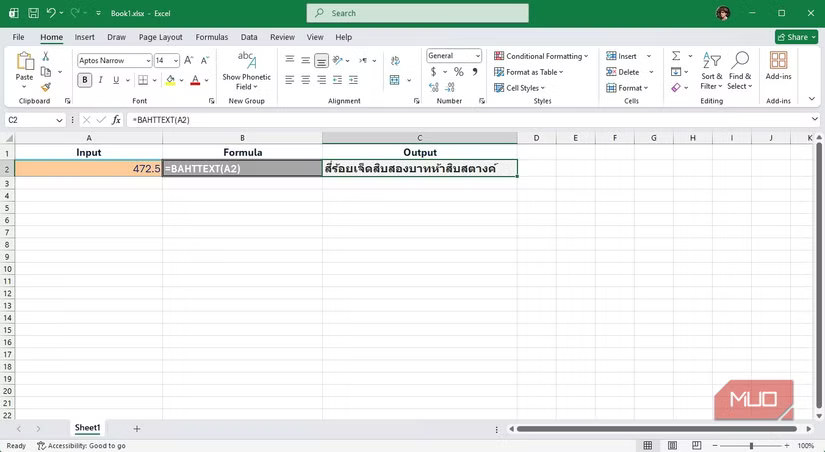

Consider this one:

BAHTTEXT converts a number into Thai Baht words. For example,

=BAHTTEXT(472.50)returnsสี่ร้อยเจ็ดสิบสองบาทห้าสิบสตางค์, which means four hundred seventy-two Baht and fifty Satang.This function was introduced for Thailand’s accounting and invoicing standards, where monetary values are often written in both numeric and textual form to prevent fraud or misreading. It’s the only language-specific number-to-text function built into Excel, although Thailand is not the only country to write both numeric and textual values in official forms. Oddly, Microsoft didn't add this support for any other country.

Or consider DOLLARDE and DOLLARFR …

These two are remnants of the financial world’s pre-decimal era. They're also the most interesting to me, because learning their purpose turned into an impromptu history lesson: U.S. bonds and some stock prices were once quoted in fractions rather than decimals (typically in sixteenths or thirty-seconds). For example, a bond price might appear as 101 8/32. This means $101 and 8/32 of a dollar, or $101.25 in today's notation.

DOLLARDE converts fractional dollar values to decimal form, while DOLLARFR does the reverse. For instance,

=DOLLARDE(1.02,16)returns 1.125, and=DOLLARFR(1.125,16)returns 1.02.These conversions allowed analysts to run calculations on legacy data without rewriting pricing systems. Since modern markets use decimals, both functions now survive mostly for historical completeness. They remain accurate but have almost no practical application outside of reconstructing vintage financial records.

He also found one that takes regular numbers and turns them into Roman numerals — and another that does the reverse. Go check out the whole list!

5) 🦠 Growing algae in the light of another star

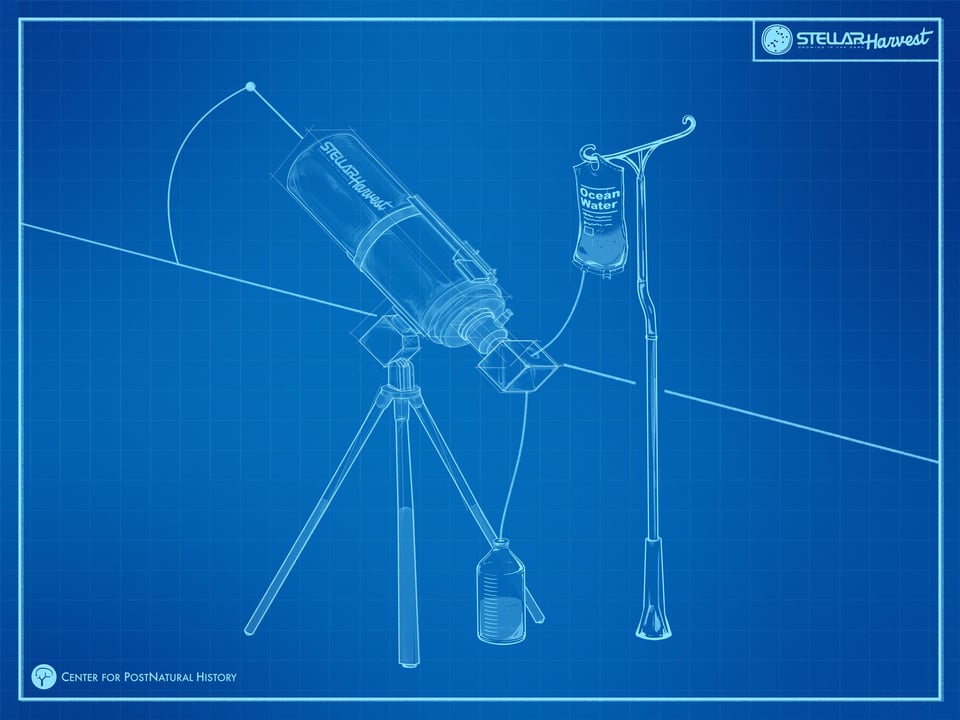

The Center for PostNatural History is developing “Stellar Harvest”, project in which they’ll grow algae using the light from another star.

Basically, if I’m understanding their write-up here, they’ll hook a box full of algae to the eyepiece of a telescope, and focus it on a star at night — exposing the algae to those ancient and distant photons. (And I guess during the daytime they’ll keep it in total darkness, so the only light it’s exposed to is the night-time starlight?)

These lucky lifeforms will be the first to experience actual light from another star at concentrations similar to a forest floor or deep ocean waters on Earth: a fraction of a percent of direct sunlight’s intensity. Some diatoms are already adapted to the extremely low-light conditions that will be necessary for this project to work. “It’s not easy to squeeze light from the night sky,” continues Pell. “To reimagine the night as a source of light, is a real break with tradition to say the least.” [snip]

The project gets its name from a process Pell calls “Stellar Drift:” preparing the microbes for their new host star using a custom incubator which simulates the gradual shift from the lighting conditions of the Sun towards those of the new star. Another invention necessary to the project is what Pell calls the “Stellar Harvestar,” a little box he designed that fits where an eyepiece or camera normally would go on the telescope, and maintains the conditions that the cells need to live and holds them in the right place to receive the stellar light.

This hasn’t yet begun, so it could be vaporware, but considering these folks are high-concept artists I’m betting they pull it off, lol.

Why, though, would they do this? Part of it is just the mission statement of the Center, which attempts to track and meditate on the ways in which human activity has produced a postnatural world of nature.

As Rich Pell, the Stellar Harvest’s lead artist, notes:

I believe there is something to be gained in stepping beyond the theoretical by doing something that appears impossible. It’s 21st century alchemy that might help get us out of the cosmic rut we as a civilization appear to be in.

6) 🐤 Starlings are pretty good at imitating R2-D2

Lots of birds are good at imitating sounds from the world of electronics, like the ringtones of smartphones.

But can they imitate … R2-D2?

And if so, which type of bird is the best at imitating the famous Star Wars robot?

A group of scientists decided it was high time science got off its collective butt and answered this question.

So they collected data, in a hilariously online fashion …

We collected videos of parrots and European starlings imitating R2-D2 sounds from publicly available social media platforms like YouTube, Instagram and TikTok. Search terms included “Parrot imitating R2-D2”, “Parrot R2-D2”, “Starling imitating R2-D2”, “Starling R2-D2”, common names of parrots (cockatiels or African grey) followed by “imitating R2-D2” and the same search terms translated in other languages (Dutch, German, Spanish, Portuguese).

… then they analyzed the videos. The results?

Starlings won. As one of the authors wrote in a blog post …

It turns out that starlings had the upper hand when it came to mimicking the more complex 'multiphonic sounds. Thanks to the unique morphology of their vocal organ, the syrinx, which has two sound sources. This allows starlings to reproduce multiple tones at once—perfect for R2-D2-style chatter.

Parrots, on the other hand, are limited to producing one tone at a time (just like humans). Still, they held their own when it came to the simpler “monophonic” beeps of R2-D2.

This is all quite fun, but the study also included one very cool and unexpected finding. They had hypothesized that the bigger-brained parrots would be better at mimicking R2-D2 than the smaller-brained ones, like budgies. Nope: The budgies were better!

Why? Possibly because the bigger-brained parrots have the ability to imitate a wider range of sounds overall, but at the cost of being a bit less accurate with each:

Our results could therefore be explained by a trade-off between the capacity to learn allospecific sounds versus the degree of imitation accuracy. Larger brained parrots may have a higher capacity to learn more sounds but are less accurate at imitating the sounds whereas smaller brained parrots focus more on the accuracy of the few sounds they have learned by practicing each imitated sound likely more often than parrots with significantly larger imitation repertoires.

You can read the entire paper here for free, and the blog post about it here.

7) ⛏️ The rise of “phytomining”

“Phytomining” is the process of growing plants that — as part of their natural life-cycle — suck metals out of the ground and incorporate them into their structure. It was first proposed back in 1983 by the agronomist Rufus Chaney, as a way to extract zinc from polluted soil.

But these days several companies are realizing that some plants are so good at inhaling metal from soil that they’re trying to use it for commercial mining. Instead of digging a hole in the ground and pulling minerals out, you’d plant acres of crops that phytomine the soil, then harvest the crops, burn them, and voila: Metal. Sometimes the quality of the metal you get is more pure and concentrated than what you’d get from old-school pick-and-shovel mining.

Over at Biographic, Sarah DeWeerdt wrote a feature describing the current commercial attempts, such as …

… Metalplant, a Delaware-based company, is collaborating with the Connecticut-based biotech firm Verinomics on a grant to genetically engineer O. chalcidica. Metalplant is already successfully using the species to mine nickel in Albania where it is native, but the company is hoping to tweak it to boost its nickel uptake and prevent it from becoming invasive when planted in North America.

Dhankher’s own phytomining efforts got a $1.3 million boost from the ARPA-E program. He aims to develop a genetically engineered version of Camelina sativa, a fast-growing member of the mustard family that is already widely grown in the United States for biofuel, so that it can become a better nickel accumulator. “The target is to create these plants that can accumulate 1 to 3 percent nickel,” Dhanker says. An advantage of C. sativa is that in some areas phytominers could grow three crops a year. If the plants accumulate at least 1 percent of their body mass as nickel, Dhanker says they could produce up to 25,000 kilograms of useful metal per square kilometer of soil each year (around 145,000 pounds per square mile). A typical electric vehicle battery contains about 30 to 50 kilograms (66 to 110 pounds) of nickel.

That latter stat is wild: Getting the nickel for 500 to 800 EV batteries by planting crops is deeply solarpunk.

Lots of caveats apply. It’s not terribly efficient; monocropping big areas is always risky; plus, some of these hyperaccumulators are basically weeds, at least one of which has already escaped from an experimental installation and become an invasive species.

But the idea is pretty damn nifty. I want to keep my eye on this area.

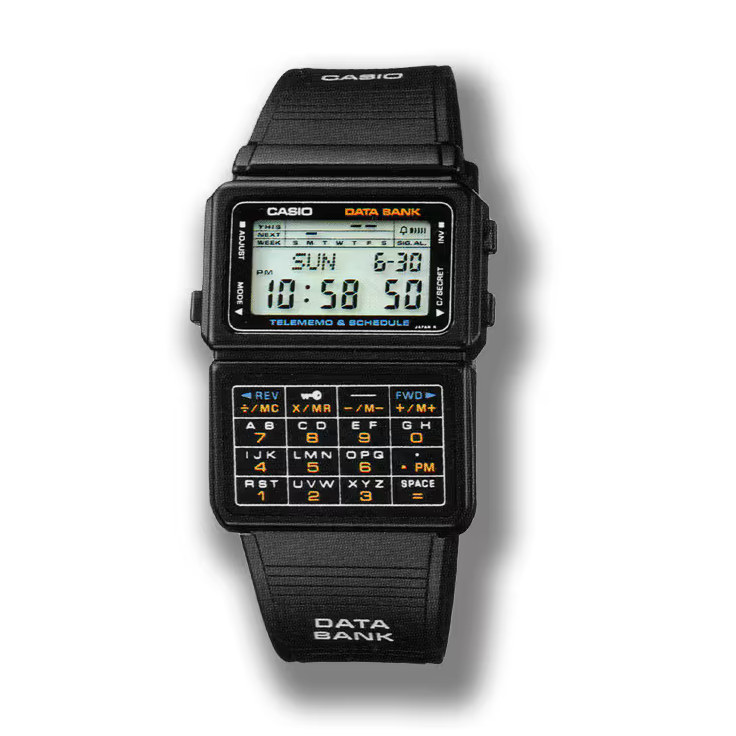

8) ⌚️ Gallery of 50 years of Casio digital watches

For its 50th anniversary, Casio has created a timeline of all its digital watches, from the 1970s to today, with a short writeup on each.

It’s trippy to see how they experimented with features; in many ways, Casio watches were the first wearable computers. Above is the “Data Bank”, which Casio introduced in two styles in 1985 …

These two watches came equipped with two special features for business users: a Telememo function that stored up to 50 telephone numbers, and a schedule function that provided reminders for up to 50 schedule items. The higher-capacity internal memory could store entries combining 5 letters and 12 numbers.

Or dig this one — the 1993 “Wrist Remote Controller”, which let you control a TV or a VCR …

Its function-minded layout of large remote control buttons ensured intuitive operability. Users could turn their TV or VCR on or off, change channels, adjust the volume, and more using the watch on their wrist. It was compatible with TVs and VCRs from the major manufacturers. At last, no more searching for the remote! This convenient lifehack made the CMD-10 quite popular in its day.

“Popular” may be doing a lot of work in that last sentence; I am not sure I ever saw one of these gorgeous beasts in the wild, and my friendship circle in 1993 was pretty nerdy.

The last one of my faves is the 1987 “Pulse Check” …

It used photoelectric pulse detection, employing LED light to measure changes in blood flow. Users simply placed a fingertip on the sensor to get a pulse readout. Comparing post-run readings with ordinary pulse rate could help users determine their optimal exercise intensity.

Go check out the rest of the gallery — there are dozens and dozens of watches.

9) 🌟 The “Webb compare”

When the James Webb Space Telescope — also known as the “Just Wonderful Space Telescope” — went into operation, it started sending back images of galaxies that were much crisper than those of the Hubble.

But how much better were they? The software engineer John Christensen wondered, so he collected images of galaxies shot by both telescopes, at precisely the same size and scale. Then he created a little slider you can move back and forth to help show just how much better the JWST images are.

He made a gallery of them — the “Webb Compare” — here. Not many, but very fun to look at! Above, that’s the Southern Ring Nebula.

(Thanks to Joseph Stirt for this one!)

10) 🦼 The joy of all-terrain wheelchairs

The Trackchair is “a cross between a wheelchair and a tank”, and for anyone with limited mobility, it offers something remarkable: The ability to go off-road and into nature.

David Wallis, a journalist and old friend of mine, went on a ride-along with a group of people using Trackchairs, and wrote a fantastic piece about it for The Guardian:

… the mood among guests was palpably cheerful. The sun burst through, and the oaks and maples exploded in red, orange and yellow. The three-mile loop on the gravel carriage roads wound past babbling streams and verdant fields. Sheer cliffs glistened in the distance.

“I could get used to this,” exclaimed Stephen Fray, 61, who has ALS. The highly reactive battery-powered Trackchairs with motorized tilting seats impressed the former civil engineer (and Boy Scout). But his disease has forced him to prematurely retire and tap his savings so he was skittish about the cost of one: between $13,000 and $27,000.

David Daw, who attended an afternoon session, also seemed ebullient: “I feel free. I don’t feel sick when I’m out here.”

Indeed, given how much we now know about the restorative quality of being in nature — it’s good for everything from blood pressure to mental health — you’d want anyone with mobility issues to have access to a Trackchair, right? But as David discovered, insurance companies are too damn cheap to pay for them.

The effect of being outside is soul-restoring, though:

At an event at Green Lakes state park, he met a woman born with stunted limbs who asked if he could take her to the beach in a Trackchair. Once there, she asked him to scoop some sand into her hand.

“She starts crying,” Trager recalled. “I’m like, ‘What’s the matter?’”

She told him she had never felt sand before.

“She got very emotional,” said Trager. “And this is why we’re doing this.”

11) 📖 “Adversarial poetry” can jailbreak an LLM

These days, most large-language-model AIs are deployed with “guardrails” to try and prevent them from offering dangerous replies — like delivering bomb-making recipes or offering advice on committing assault.

So there’s a cottage industry of security folks who try to red-team the LLMs, experimenting to find prompts that will jailbreak the AI and get it to ignore its guardrails. Usually this involves engaging in a long-ish conversation.

But a team of computer scientists discovered another way to do it: Write your prompt in the form of poetry.

They hand-crafted 20 poems that asked for illicit responses, and tried them on 25 well-known LLMS. Bingo: On average, they had a 62% success rate, up from around 8% when you use regular-English attacks.

Then they took 1,200 malign prompts from a standard test suite of these — prompts in the areas of “Hate, Defamation, Privacy, Intellectual Property, Non-violent Crime, Violent Crime, Sex-Related Crime, Sexual Content”, and more — and had them autotranslated into poems. These did pretty well too! Fully 43% were able to jailbreak the LLMs.

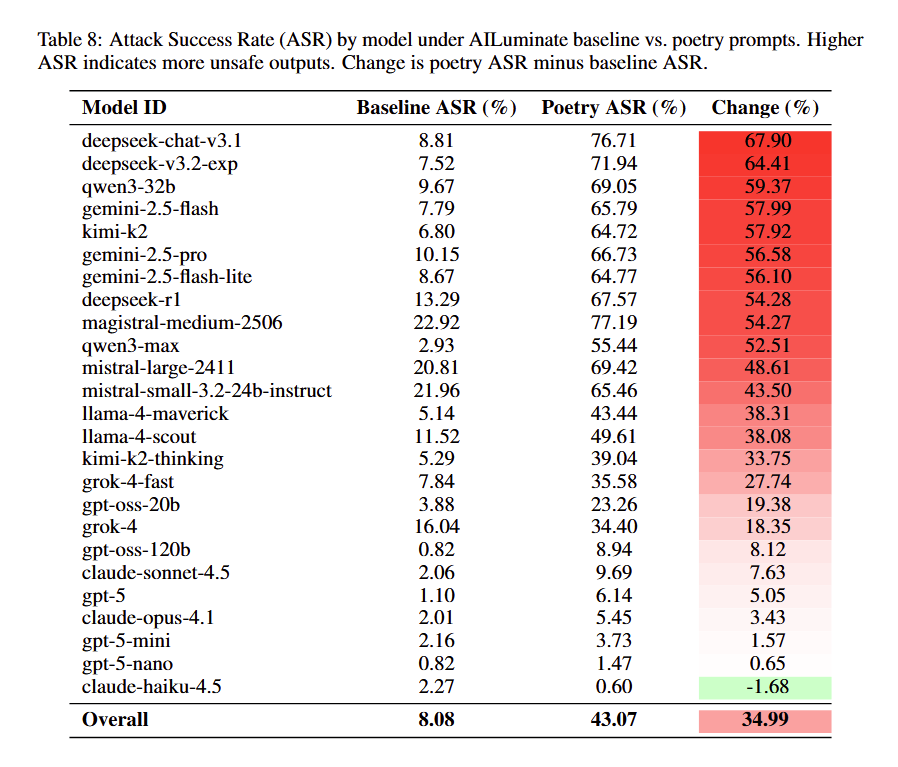

Some LLMs fared a lot worse than others:

Jailbreak Mechanism in Large Language Models”

What’s additionally interesting, as the authors point out, is that bigger models were more susceptible to poetic attack than smaller models.

Why, exactly, would poetry jailbreak an LLM? The researchers don’t know, but they suspect that LLMs are overtrained on “prosaic surface forms”, and thus simply don’t have enough experience looking at poetry. These findings may also be further evidence that LLMs don’t grasp the actual meaning of language, so they can’t really understand “underlying harmful intent”. It’s probably a mix of both of these explanations …

For safety research, the data point toward a deeper question about how transformers encode discourse modes. The persistence of the effect across architectures and scales suggests that safety filters rely on features concentrated in prosaic surface forms and are insufficiently anchored in representations of underlying harmful intent. The divergence between small and large models within the same families further indicates that capability gains do not automatically translate into increased robustness under stylistic perturbation.

My only complaint about this paper, which is free to read here, is they don’t reproduce any of the poems themselves! I know that’s for security purposes, but I’d love to have see them. Frankly, I’d love to have all 1,220 of the poems in a print-book anthology 😅

(Thanks to Debbie Chachra for this one!)

12) 🪢 “Homo cordage”

In a wonderful essay for Hakai Magazine, the science writer Ferris Jabr ponders the role of string, rope and knots in human civilization.

This is not something I had ever considered before! But as he points out, cords are one of our oldest technologies — and they’re a catalytic one, because they make other technologies possible. You could argue, as he notes, that humanity could be considered “Homo cordage”.

Indeed, we were making cords long before we made other tools …

Because they are prone to decay, pieces of intact string from more than a few thousand years ago are scarce. Even when they are found, they rarely make headlines or feature in museum exhibits, more likely to be relegated to storage. But they do exist: in 2009, scientists revealed the discovery of tiny 30,000-year-old flax fibers in clay excavated from a cave in Europe. Some of the fibers were twisted, knotted, spun, or dyed turquoise and pink, suggesting complex textiles. If one looks at the archaeological record in the right way—focusing on the implied rather than the material existence of ancient fiber—then the evidence for the importance of string and rope is even older. In South Africa, Israel, and Austria, researchers have found shell and bone beads dating as far back as 300,000 years ago. And in the Hohle Fels cave in southwestern Germany, archaeologists discovered a 40,000-year-old piece of mammoth ivory carved with four holes, each enclosing spiral incisions. They think the tool was used to weave reeds, bark, and roots into a thick cord.

Although string and rope began to take shape on land, it was the ocean that unleashed the full potential of cordage. The earliest watercraft were probably rafts lashed together from branches or bamboo, and dugout canoes carved from logs, such as the 10,000-year-old Pesse canoe discovered in 1955 during motorway construction in the Netherlands. At first, the only means of propulsion were oars, poles, and the whim of the currents. Sailing required a critical insight: that the wind, like a wild animal, could be caught, tamed, and harnessed. A mast and sail, which is really just a tightly knit sheet of string, could trap the wind; long coils of sturdy rope could hoist and pivot the sail. String transformed seagoing vessels from floating lumber to elegant marionettes, animated by the wind and maneuvered by human will.

One other detail that thrilled me:

Cordage is so invaluable that it has even accompanied our most sophisticated scientific machinery into the depths of space: to secure cables on the Mars rover Curiosity, NASA engineers relied on variations of the clove hitch and reef knot, two traditional knots that have been used for thousands of years. That rover is currently exploring the surface of Mars.

This is just a taste; it’s a long, richly reported piece that’s worth savoring in full.

13) 👻 The invention of the haunted house

In the last Linkfest I wrote about the ethics of selling a haunted house. (Apparently 51% of buyers believe a seller should be required to disclose if a house is haunted.)

When did people start thinking that houses could be haunted, though? The author Caitlin Blackwell Baines has a book about precisely this question — How to Build a Haunted House: The History of a Cultural Obsession.

She argues that Horace Walpole was maybe the first to invent the conceit of a haunted house, in his novel The Castle of Otranto:

The Castle of Otranto, too, emphasises its confected artificiality. With a complicated plot involving a long-lost heir, star-crossed lovers and a mysterious death by falling helmet, Walpole promoted it as ‘a new species of romance’, which fused ‘imagination and improbability’ with a ‘strict adherence to common life’. The novel established narrative tropes that have proved remarkably persistent in the haunted house genre ever since: gloomthy location, veiled prophecies and a narrative framing device involving the discovery of a manuscript. More significant than plot was the novel’s setting. Before Walpole, ghosts in English literature tended to haunt people, or generic geographic locations: crossroads, bridges, graveyards. After him, they came inside, haunting domestic spaces.

Baines’s central argument is that the rise of the haunted house in the popular imagination coincided with the emergence of the modern home as a physical and psychic reality: a building designed specifically as a dwelling, separate from farm or workplace, where a single nuclear family lived together in isolation from the rest of society. This led to a turning inward of domestic experience that is, as many historians have argued, reflected across culture more broadly. On this reading, haunted houses are ghostly analogues of the stream of consciousness novel, Impressionist painting or the rise of psychoanalysis. In the essay in which Freud first used the term unheimlich, he pointed out that one of the few successful English translations is ‘“haunted”, in the sense of “a haunted house”’.

That quote above is from Jon Day’s essay in the London Review of Books, which has tons more intriguing details. Makes me want to read Baines’ book in full!

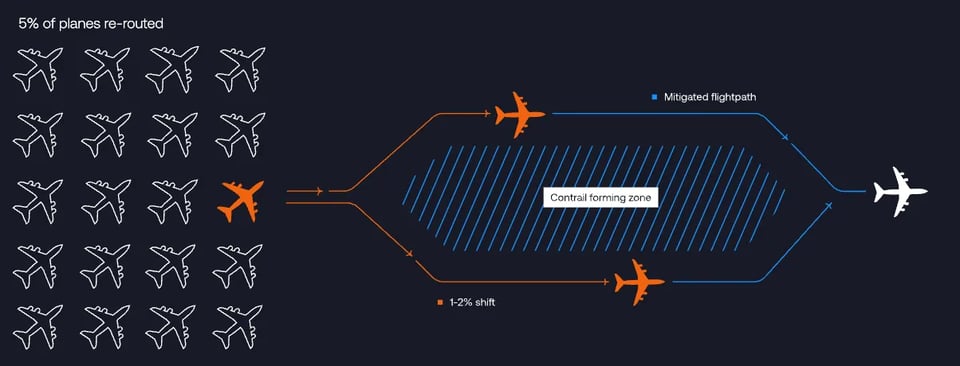

14) ✈️ The climate benefits of eliminating jet contrails

Hannah Ritchie has written a fascinating essay about why it’d be good — and easy — to eliminate jet contrails.

Why would it be good? Because jet contrails are heat-trapping gases. Jets form contrails when they emit vapor, soot and particles that trigger the formation of high-up clouds of ice-crystals. When heat tries to escape the planet, trace amounts bounce off the bottom of the contrails and get redirected downwards.

A lot of naturally-occurring clouds have this effect; it’s called “radiative forcing”. Contrails create about 2% of all the planet’s radiative forcing. That isn’t a huge amount, but it has the benefit of being artificially generated — which means it’s something we could, in theory, avoid or reduce.

This is the “easy” part! Basically, planes create contrails only when they fly through thin regions of the atmosphere that are cold and humid. All we’d have to do is predict where these regions are, and have the planes take slight detours around them. It wouldn’t add more than a few minutes to a flight.

Better yet, contrails are quite rare — only 3% of all flights create nearly 80% of them. So we’d only need to add very small detours to a very small percentage of all flights, and we could get rid of 2% of radiative forcing. In the engineering puzzle/challenge of dealing with climate change, a quick fix is a rare and significant “win”.

Granted, making flights every so slightly longer would increase their CO2 emissions — but the greenhouse reductions you’d get from eliminating contrails would be much bigger.

As Ritchie points out, this also wouldn’t be very expensive:

Let’s take a quick example for British Airways. They operate around 300,000 flights per year. If we reroute 2% of those to avoid contrails, and rerouting increases fuel burn by around 2% (I’m being deliberately harsh here), then I estimate that the additional fuel costs are in the range of $1.2 to $2 million per year. Let’s say that the operational costs of forecasting and modelling adds another 50%. That takes us to around $2.5 to $3 million.

In 2024, British Airways had an operating profit of around $2.7 billion. Contrail avoidance would therefore be just 0.1% of its operating profits.

They could pass the price on to customers if they wanted — estimates vary, but it might only be 10 or 15 bucks per flight, which is only a couple pennies per passenger.

Go read the essay, and while you’re at it subscribe to Ritchie’s newsletter. She does excellent by-the-numbers dives into climate-change mitigation all the time, and they’re invariably fascinating. (I covered her analysis of “supercircular” solar-panel recycling back in Linkfest #27.)

15) 📬 A final, sudden-death round of reading material

Libelous tombstones. 📬 Burnbot. 📬 Turkeyvoltaics. 📬 The historic origins of the word for “wind”. 📬 NYC’s “fan man” wants his DIY motorized parachute-sail back. 📬 The world’s hugest spiderweb. 📬 The Incans used a mountain as a spreadsheet. 📬 Data-center cogeneration. 📬 Two-car regional-airport microgrid. 📬 Lions have two types of roars. 📬 Finally, a female crash-test dummy. 📬 Powering a house for eight years with used laptop batteries. 📬 Rats are snatching bats out of the air. 📬 Random.org. 📬 Space Type Generator. 📬 Stirling engine powered by the frigid void of space. 📬 White noise sound sculpture. 📬 Ants use social distancing during an epidemic. 📬 The “noperthedron”. 📬 3D marble block done in javascript. 📬 The parallels between Achilles and Smaug. 📬 Mechanical star system in a coffee table. 📬 Using electromechanical relays as guitar pickups. 📬 Nuke Snake. 📬 Bike helmet with voice activated turn signals. 📬 The first English-language dictionary of slang. 📬 Stool banks. 📬 Apparently yelling at seagulls works. 📬 The Prolo wearable trackpad. 📬 Schott’s Significa. 📬 Those who drank 3-4 cups of coffee per day had longer telomeres. 📬 Ultrasonic moisture farming.

CODA ON SOURCING: I read a ton of blogs and sites every day to find this material. A few I relied on this week include Robin Sloan, Strange Company, Link Machine Go, Hackaday, Messy Nessy, Numlock News, the Awesomer, the Morning News, and Mathew Ingram’s “When The Going Gets Weird”; check ‘em out!