Linkfest #3: "Cistercian Numbers", Robots That Hug, and Dice That Roll Negative Numbers

1) 🧮 Cistercian numbers

I'd never heard of Cistercian numbers before, until I stumbled upon this brief post describing them ...

Cistercian numbers are an ancient numeration system invented by the order of Cistercian monks in the 13th century. Its peculiarity is that it can represent very large numbers in a more compact format than both Roman and Arabic numerals.

If you look at that pattern above, you can see how it works. To denote a number from one to nine, you use different patterns that branch off of the top right of a vertical line. The top left patterns denote ten to ninety; bottom right does the hundreds, and lower left the thousands. You can blend all four quadrants together to produce a single icon representing a four-digit number.

It's pretty ingenious! I don't know how practical it is, but graphically it's super cool: These look like glyphs you'd see on the side of a crashed UFO in the Arizona desert.

For more Cistercian fun, you can read the blog post of this developer who created a set of web components that display the time using Cistercian numbers. It looks like this ...

Source code for that clock is here ...

2) 🤖 How to build a robot that hugs

Human hugs are surprisingly complex, as Max Planck Institute for Intelligent Systems discovered -- when they made HuggieBot 3.0, a robot that gives out hugs.

Obviously, they had to make sure the robot wasn't too strong; you don't want an android crushing your ribcage like a set of toothpicks. But they also had to make the robot's limbs soft and warm, this latter fact which provoked in me a slightly Freudian shudder. (Warm-blooded robots freak me out, apparently).

Most importantly, though, they had to program in "intrahug gestures" ...

Part of making hugs enjoyable for humans involves the use of intrahug gestures, the development and test of which is one of the major contributions of the new paper. Intrahug gestures are the things you do with your arms and hands midhug, and while you may not always be consciously aware that you’re doing them, they could include things like gentle rubbing, pats, or squeezes.

The hug “background” gesture is a hold, but (and you should absolutely try this at home), just doing an extended static hold-type hug will definitely make a hug feel kind of robotic. Human hugs involve extra gestures, and HuggieBot is now equipped for this. It’s able to classify the gestures that the human makes and respond with gestures of its own, although (to avoid being too robotic) those gestures aren’t always directly reciprocal, and sometimes the robot will initiate them independently.

Interestingly, because the intrahug gestures occur with some randomness, "no two hugs from the robot will ever be identical."

Apparently people enjoyed the hugs ...

Hugs were described as “a comforting hug from a mother,” “a distant relative at a funeral,” “receiving a pity hug from someone who doesn’t want to,” and even “hugging a lover.”

My usual emotional-manipulation caveats aside (I'm dubious of the ethicality of robots designed to trick us into liking them), the research here is interesting, and possibly quite useful -- insofar as it's good to understand how to build robots that we can interact with very physically without getting hurt. (The original HuggieBot paper is here, if you want to read it.)

3) 🌲 The gnarled shape of old trees is part of why they live so long

"Wander To Ancient Bristlecones" by Matthew Dillon (CC 2.0 license, unmodified)

That picture above? It's a bristlecone pine, a tree that can live for hundreds of years, or even thousands; oldest known bristlecone is fully 4,850 years old! You can recognize them by their gnarled, twisty shapes, which fairly exude age.

It turns out those twists and turns are an organic part of why the trees last so long. A group of scholars in Spain (led by Sergi Munné-Bosch) recently identified 12 pine trees that were around 660 to 750 years old, and found they shared a few characteristics. As the New Scientist reports (in a paywalled piece alas) ...

The team noted that the 12 ancient trees shared a number of striking characteristics. Most pine trees have a main central trunk that grows more strongly than its side branches – a trait called apical dominance – but all the ancient trees had thick side branches that competed in size with the central trunk.

These side branches often took unusual, twisted forms, suggesting these trees had a high ability to adapt to changes in the environment, known as plasticity, says Munné-Bosch.

Another common feature was “modular senescence”, meaning that large sections of the trees were dead while the rest continued to thrive and sprout new shoots. This is another sign of plasticity, since it suggests that ancient trees can survive damage by sealing off the injured parts, says Munné-Bosch.

If gnarled-ness is a good sign up serious age, this is a useful bit of knowledge! For one, it'll be easier for conservationists to quickly visually identify super-old trees, making them thus easier to protect. Nobody yet knows whether the twistedness of the pines is correlation or causation, though; are the biological mechanisms that make them twisted a cause of their longevity or just a symptom of it?

4) 🚀 Inside "Globus", a Soviet cosmonaut orbital-guidance device

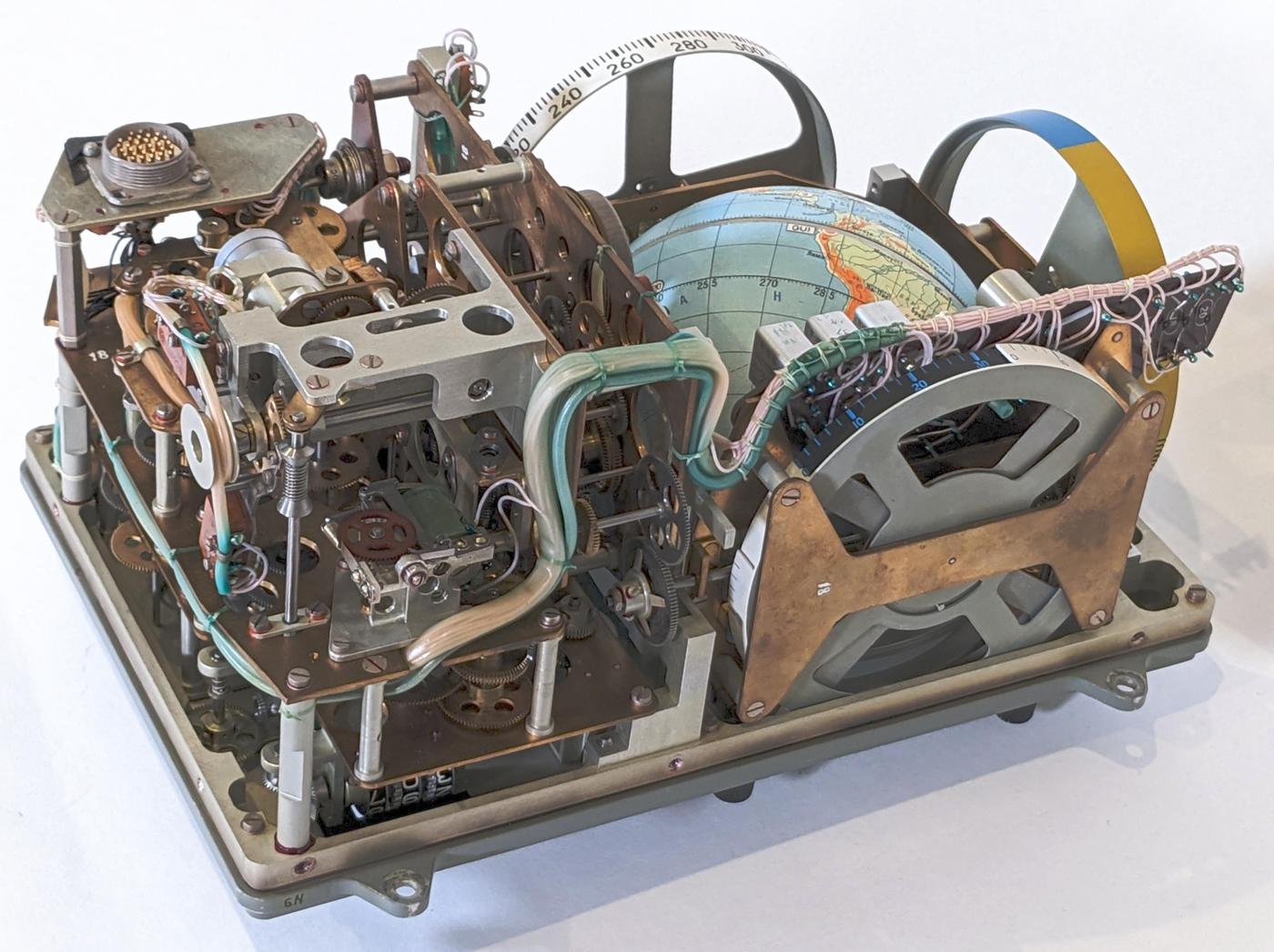

Ken Shirrif has done a fascinating teardown of "Globus", an orbital computer that Soviet cosmonauts used to figure out where precisely above the earth they were orbiting.

I say "computer", but this was a gloriously analog device, executing analog computations via a truly cunning and gorgeous seat of steampunk gears that would rotate according to trajectory co-ordinates input by the cosmonauts. It was a clockwork mechanism, unconnected to any outside directional data -- it didn't know really where it was, it was just predicting its location. As Shirrif writes ...

The globe rotated while fixed crosshairs on the plastic dome indicated the spacecraft's position. Thus, the globe matched the cosmonauts' view of the Earth, allowing them to confirm their location. Latitude and longitude dials next to the globe provided a numerical indication of location. Meanwhile, a light/shadow dial at the bottom showed when the spacecraft would be illuminated by the sun or in shadow, important information for docking. The Globus also had an orbit counter, indicating the number of orbits.

The Globus had a second mode, indicating where the spacecraft would land if they fired the retrorockets to initiate a landing. Flipping a switch caused the globe to rotate until the landing position was under the crosshairs and the cosmonauts could evaluate the suitability of this landing site.

You really have to check out all the photos of Globus' internal gears. It's an astonishing piece of engineering!

5) 🎨 Gorgeous collection of Japanese art grad-student projects

Over at Spoon & Tamago -- a blog devoted to Japanese art -- they have a tradition of highlighting awesome work by recently-graduating students.

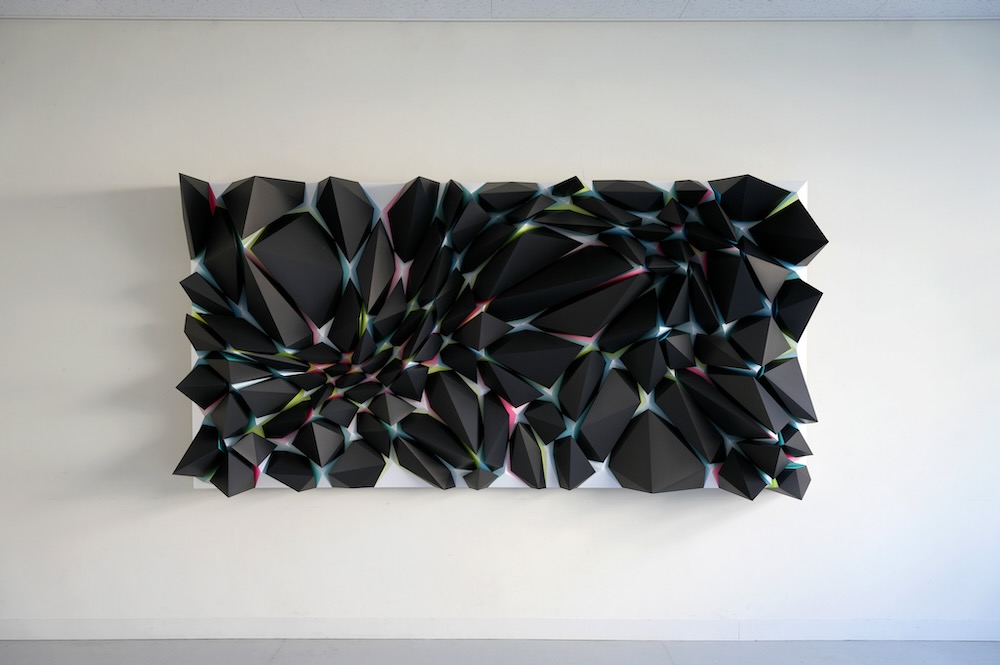

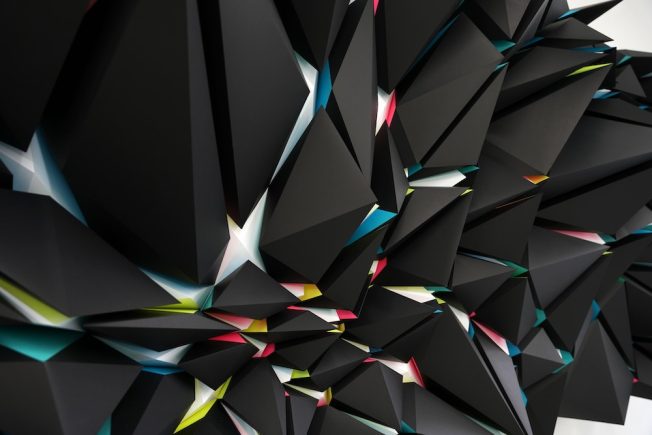

Their post with this year's highlights is pretty rad. That picture above is an abstract paper wall-mounted sculpture by Tsuzuki Endo; here's what it looks like in closeup ...

Go check out the rest of the post, which has gnarly oils, tea-stained plastic, and crystal versions of paper cranes. There's plenty more in Spoon & Tamago's archive of their previous posts on grad-student art.)

6) 👀 Early Christian monks' battle with distraction

It might sound weird, but the early Christian monks were plagued with a lot of distractions. Because they renounced the world, the world got interested in them. They seemed ... usefully impartial? So monasteries were flooded with visitors bugging them for advice and offering them money. Monks actually had to work pretty hard to avoid the duck-pecking distractions of the outside world. Plus, they were trying to quieten their minds so they could pray more attentively, and connect with the eternity of the almighty.

Jamie Kreiner has written The Wandering Mind, an account of the early monks' mental struggles with distraction, and judging by this review in the Wall Street Journal -- here's a free "friend" link in case you're not a subscriber -- it looks fascinating.

She argues, in essence, that our modern Western fears about our easily-distractable minds have a direct lineage from the monks ...

Their time, Late Antiquity (roughly A.D. 300 to 900), resembles ours: Society is in a state of flux and “it feels like things are declining rapidly.” Our ethical qualms about distraction, Ms. Kreiner argues, are a monastic legacy, because it was the monks who cast distraction as a “moral crisis” in the first place. The ostensibly secular West, she writes, carries “a set of cultural values surrounding cognition that are very specifically monastic and, to an extent, specifically Christian.”

In Hellenistic and Stoic thought, “attentiveness” to mental processes leads to self-control. Distraction (perispasmos) is external and keeps us from doing philosophy. For the early monks who inherited this legacy, distraction was an original sin of the mind, and the war to concentrate was a “primordial struggle” against “demonic antagonism.” The divided attention reflected a divided self, cut off from God. Gossip and concern with other people’s business led the mind astray. For Plutarch, writing in the first century A.D., “nosiness” harms society by making us rude and unproductive. The 4th-century monk John Cassian held that curiositas is immoral because it makes us inwardly “dissatisfied and incapacitated.” The modern morality of attention, Ms. Kreiner suggests, fluctuates between these views.

I'm gonna order this one.

7) 🎲 Nested dice that can produce negative numbers

Here's a cool concept: "DUO DiCE", a set of six-sided transparent dice that contain -- inside each die -- another die. The internal die can have four, six, either, ten, twelve or twenty sides.

And the wild thing is that inner and outer die interact, based on the color scheme of the internal die. If the internal die is blue, you add the two dice together. If the internal die is red, you subtract the internal die from the external die.

You can see that in the example depicted above: The top result gives 8, the lower result gives 2.

But here's the fun wrinkle: If the internal roll is bigger than the external roll, you produce a negative number. Like, if the external roll is 5 and the internal roll is a red 11, you've just rolled ... negative 6.

This, as the creators point out, adds some fascinating chaos if you paired it with traditional board games. Imagine playing a game of Monopoly where you could roll a negative four, and have to skip backwards four positions on the game board.

I'm ordering a set of these! As with all Kickstarter projects, it's a calculated gamble as to whether they'll actually ship the product. But I'd love to get my hand on these. I'd be intrigued to see how they reinvigorate and weird-ify existing games (imagine playing D&D with negative rolls!), and I'd also be intrigued to see if I could design entirely new games with such oddball dice.

8) ⏰ A clock that tells time by knitting

Siren Elise Wilhelmsen is an artist who has created a clock that tells time by knitting a scarf. It has a mechanism that slowly goes around a circle, slowly adding stitches, with the scarf gradually growing longer and longer.

Time is manifested in physical objects; in things that grow, develop or extinguish. Time is an ever forward-moving force and I wanted to make a clock based on times true nature, more than the numbers we have attached to it. - Siren Elise Wilhelmsen

365 Knitting Clock stitches time as it passes by. It knits 24 hours a day, one year at the time, presenting the physical representation of time as a creative and tangible force. After 365 days the clock has turned the passed year into a two-meter long scarf. Now the past can be carried out into the future and the upcoming year is hiding in a new spool of thread, still unknitted.

I am super into any technologies that use knitting as the medium for recording data. The data here is time -- but I'm thinking also about the Montreal city councillor who would knit during council meetings and switch colors when men or women would talk; since the men spoke disproportionately often, the scarf became a dataviz -- and a wonderfully meta one, given knitting's status as an art form performed mostly by women.

9) 🎳 A final, sudden-death round of reading material

What happens when AI runs out of things to read? 🎳 Tabs are coming to Microsoft's Notepad. 🎳 Theories about social-media feeds considered as "algorithmic folklore". 🎳 The "order force" rule of how we deploy multiple adjectives in English. 🎳 What type of abrasive grit did Galileo use to grind his telescope lenses? 🎳 The source code for the Furby. 🎳 DIY chloroform. 🎳 A green comet will pass Earth. 🎳 Why Sandro Botticelli's paintings of hair enraged the church. 🎳 An "aggressive, stealthy web spider". 🎳 Recovering the sound of Alexander Graham Bell's voice. 🎳 Modernizing OS/2 Warp. 🎳 AM radio is so power-hungry they're shutting it down in the UK. 🎳 Sales of paper maps are exploding. 🎳 Why online chess is booming so much it's crashing Chess.com's servers. 🎳 How dogs perceive time. 🎳 One of the most intriguing tremolo guitar pedals I've ever seen. 🎳 Some calculations arguing that abandoned mines could make terrific gravity batteries for renewables. 🎳 Women in the age of polar exploration. 🎳 When US navy sailors wrote their deckwatch entries as poetry. 🎳 Nine-year-old girl finds a five-inch megaladon tooth. 🎳 The "Radium Age" sci-fi of the MIT Press. 🎳 The cameras on Voyager 1 might still work. 🎳 The power of "cyclic sighing".