Linkfest #23: Zero-Dimensional Pong, "Null Island", and A Social Network For Whales

Hello all!

It’s time for my latest “Linkfest” — i.e. "the opposite of doomscrolling”, in which I harvest the Intertubes for the finest material on science, culture and technology.

Thanks again for being a subscriber! If you’re enjoying it, spread the word far and wide — forward this email to literally anyone on the planet who needs diversion. There's a pay-what-you-want signup here; the folks who can afford to contribute help keep it free for everyone else.

Let’s start ...

1) 🏢 The “New York Sign Museum”

I love old-school commercial store signs. Hand-painted, individually crafted to be one-of-a-kind, letterboxed and lit up and fashioned from curving loops of neon: They’re an industrial art form!

So I was delighted to discover there is a New York Sign Museum. When a NYC business closes, they’ll offer to remove and archive its classic sign. The museum is the passion project of David Barnett, who himself runs a design studio for signs. So far he’s collected about a hundred.

As Laura Preston writes in The New Yorker …

In 2021, the Essex Card Shop, in the East Village, pledged its hand-painted sign to Barnett after the business moved. When he arrived to collect it, the shop had been seized by pigeons. The sign came down in a shower of guano. “Some of these signs are biohazards,” he said.

Barnett’s taste for signs began in childhood. His grandmother lived in Queens and did not drive. Together, they would walk Metropolitan Avenue. “We’d go to the butcher, the baker, and the market, and everyone knew her name,” he said. “The signs became symbolic of that old utopia.” Today, all those signs are gone.

The museum is headquartered in an old dress factory in East New York, in the same building as Noble Signs, a design studio that Barnett co-founded, in 2013. While the museum conserves old signs, Noble Signs makes new ones in the old tradition. Barnett takes museum visitors by appointment. The permanent collection stands at nearly a hundred. His Queens assortment includes a colossal red “PIANOS” from Swan Piano Co., in Sunnyside; H. Goodman Furs, from Forest Hills, its letters sportively askew; and the entire façade of Jones Surgical Co. (“SICK ROOM SUPPLIES”), which was tiled in emerald-green porcelain steel.

Currently the only way to see the collection is to email them and arrange a visit. They’ve got an online database but it only has pictures of twelve of the signs … man, I wish some web designer and photographer would help them out and get the rest of their 100 signs into an online gallery. People would love to see these!

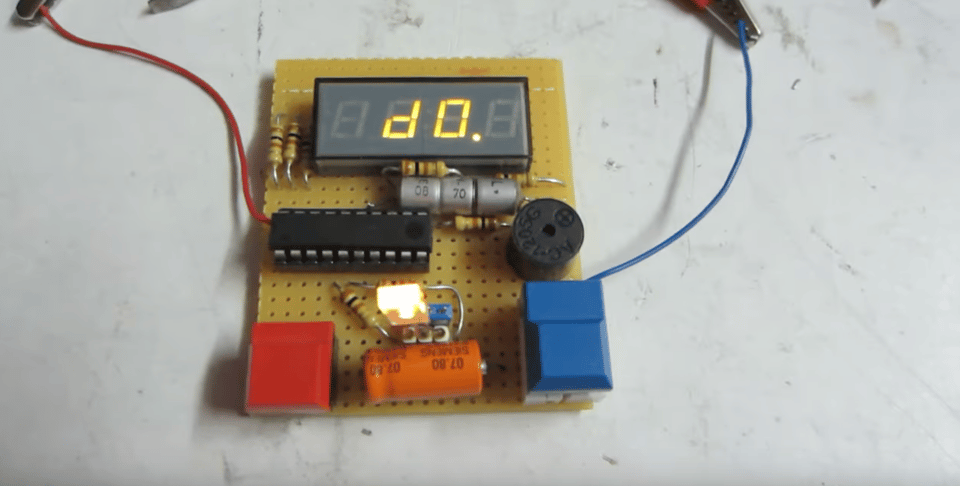

2) 🎮 Zero-dimensional Pong

Lots of hardware hackers have created “one-dimensional Pong”; it’s a single line of LEDs, where the pong ball bounces from one side to another, and to hit the ball back each player has to time their button-push to the precise moment the ball arrives at their end.

But now comes a game the creator calls “Zero-dimensional Pong”.

It’s … pretty nutty! As he describes it in this video (this link queues the video to the precise moment of his description), imagine you were at one end of a 1D Pong game, looking at it lengthwise, almost as if you were peering down a tunnel. As the ball gets closer to you, you’d see it getting brighter and brighter. To serve the ball back, you have to wait for its moment of peak brightness and hit your button.

So the entire game is just one single LED that slowly fades from green to red and back again. One player is red; the other is green. Each player watches the LED as it transitions in color, and tries to hit their button when the color is brightest.

Obviously, this game isn’t actually zero dimensions, much as the one-dimensional pong isn’t actually just one dimension … but hey, let’s enjoy the poetic license. It’s a pretty nutty project and I might attempt my own build of it; the creator, senily64dx, has documented the hardware and code really nicely.

3) 📝 Did Yosemite Sam ever actually say “What in tarnation?”

Over at Mental Floss, Ellen Gutoskey asks the question — did the famous Looney Tunes character ever actually say this phrase?

Yosemite Sam is generally considered, as she notes, to be “the poster child for the expression.” And when she looked at more-modern versions of the cartoon, she did indeed find examples of him saying it, from 1992 to 2013.

But he doesn’t seem to have said it during the cartoon’s original run from the 1940s to the 1950s:

We couldn’t find a single instance of his saying the word tarnation in any original Looney Tunes cartoon, starting with his debut in 1945’s “Hare Trigger” and ending with 1964’s “Dumb Patrol.” And even if one did happen to slip by us, that’s hardly enough to earn tarnation (or What in tarnation?) the distinction of being an iconic catchphrase of the character. Far more often can you find Sam yelling “Great horny toads!” or leveling insults at Bugs Bunny—especially varmint (a pesky animal) and galoot (“an awkward or uncouth fellow,” per the OED).

It seems to be a fascinating combo of The Mandela Effect (i.e. viewers mistakenly remembering Yosemite Sam saying it back in the day) with citogensis (those viewers later writing about how it was his catchphrase, and thus providing “proof” that he had).

BTW, I won’t spoil it, but go read the piece to find out what, precisely, “what in tarnation?” means.

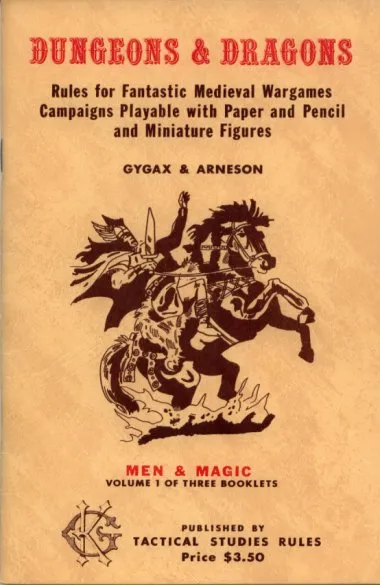

4) ⚔️ Dungeon & Dragons isn’t medieval

Dungeon & Dragons has long been understood to be a game loosely set in medieval times; the original book-cover copy, written by Gary Gygax himself, calls it “Rules for Fantastic Medieval War Games”.

The way you advance in a feudal society is to win glory in battle for your overlord. Then he grants you land, which is the main form of wealth. Unless you’re a peasant. Then you can never advance at all.

That’s not at all what happens in D&D. There is no overlord to grant you land. Land, instead of being a form of wealth, is completely free! (“At any time a player/character wishes he may select a portion of land (or a city lot) upon which to build his castle, tower, or whatever. The following illustrations are noted with the appropriate cost in Gold Pieces.”) The cost of building a structure is merely the a la carte cost of all its architectural elements. It costs nothing at all to acquire the land to build on, even inside a city.

As the author continues …

The government suggested by the player’s “barony” is almost completely a-cultural. A player builds a stronghold, and then they can extort money from the surrounding people. This is the structure of every non-nomadic human society. The only European element is the technology level of your stronghold: it has merlons, barbicans, etc.

The D&D weapon list has a medieval feel to it, but partly that’s just because that’s what we’re expecting to find. In fact, it’s a sort of survey of (mostly) pre-gunpowder weapons. Most of the weapons and armor appear in ancient Europe and in Asia as well as in medieval Europe.

So if it isn’t a medieval world, what is it?

All over, the D&D rules seem to be explicitly eschewing a medieval, feudal model in favor of a cash-based economy, a nonexistent or powerless government, and a social-classless society in a sparsely inhabited, unforgiving world.

If the OD&D rules suggest any government at all, it is a meritocracy, or more precisely, a levelocracy. Creatures with more XP and hit dice rule lower-level ones, from settled barons and goblin kings to wandering bandits and nomads. This is not only non-medieval, it is anti-feudalistic and anti-aristocratic. Level requirements for baronies are at odds with the hereditary gloss added to D&D in nearly every subsequent setting.

OD&D also exhibits an obsession with money-gathering for its own sake that is suggestive of mercantilism or capitalism.

D&D is not “fantastic-medieval.” It’s not even “fantastic renaissance” or “fantastic-post-apocalyptic.” It’s “fantastic American history.”

As the author writes, Gygax seems more inspired — consciously or unconsciously — by the terra-nullius ideology of the Europeans who colonized the Americas: It’s a world where you show up, grab land, and demonstrate your worth by advancing in skill levels.

I’ve included only a few of the highlights here; the whole essay is incredibly thought-provoking, so go read the whole thing!

5) 📸 Using traffic-cams to take selfies

Behold TrafficCamPhotoBooth, a fun little web app that lets you use traffic cameras in NYC to take pictures of yourself.

It works like this: When you’re in NYC, load the web site on your phone (it only works on mobile), give it your location, and it’ll find you the feed of the nearest live traffic-cam. You position yourself so you’re in the image and it’ll snap a pic of you.

As the creator, Morry Kolman, told NBC New York …

Kolman, an NYC-based artist, said the inspiration for the project came from a class he was taking from another artist – who challenged their students to take a picture without being the one behind the camera.

“And then, I was thinking, how can I take a picture without taking it?” Kolman said. “I can use pictures that are taken of me around the city, right? And you know, I kind of talked about this on the website, but these cameras are not made for people, right? They’re made for cars, but at the end of the day, people still get caught up in their lenses.”

This reminds me of the Surveillance Camera Players, an art project that would go out into public or commercial areas that had tons of security cams, and perform plays specifically for those cameras.

6) 🐋 A social network for whales

I just discovered HappyWhale, a super cool citizen-science web site: If you see a whale, snap a picture (ideally with GPS coordinates) and upload it. Scientists use visual machine-learning to try and identify that specific whale. Apparently if you can get a picture of the whale’s fluke, it’s the best way to identify it — they’re like fingerprints for whales, very unique.

Thus far, there are over 1.1 million submissions to HappyWhale, and they’re helped scientists identify 100,000 individual humpbacks.

Because whales are pretty mysterious and invisible most of the time, the web site is apparently transforming our understanding of how whale populations rise and fall, as Emily Anthes reports …

“Happywhale has revolutionized our field and has made large-scale collaborations possible,” Dr. Pack said.

Earlier this year, Mr. Cheeseman, Dr. Pack and dozens of other researchers used Happywhale’s image recognition tool to estimate humpback whale abundance in the North Pacific from 2002 through 2021. Initially, the population boomed, climbing to about 33,500 whales in 2012.

But then it dropped sharply. This population decline coincided with the severe marine heat wave, when Dr. Pack last spotted Old Timer. It lasted from 2014 to 2016 and slashed the supply of fish and krill. “There’s a lot more we want to learn about the event, but it is quite clear: warmer waters mean food is less available overall, and what is available is more dispersed and deeper,” Mr. Cheeseman said in an email.

It has also helped track Old Timer, the oldest humpback in existence — it was first spotted in 1972.

If you want to see some whale sightings (or penguins or polar bears; it now tracks lots of marine beasts) go to HappyWhale’s mapping tool, pick an animal and a time frame (pro tip: select five years at a time to get lots of sightings) and the map will show you links to sightings, with pix!

7) 👗 How to make a glass dress

Crescent Shay is a designer who makes clothing using super witty concepts — she’s made a dress out of pennies, and 2D-looking clothes, for example. Recently she decided to make a dress out of glass.

Okay, technically it’s resin, not glass — but it’s still extremely cool, and the trial-and-error in her process is wonderful to behold.

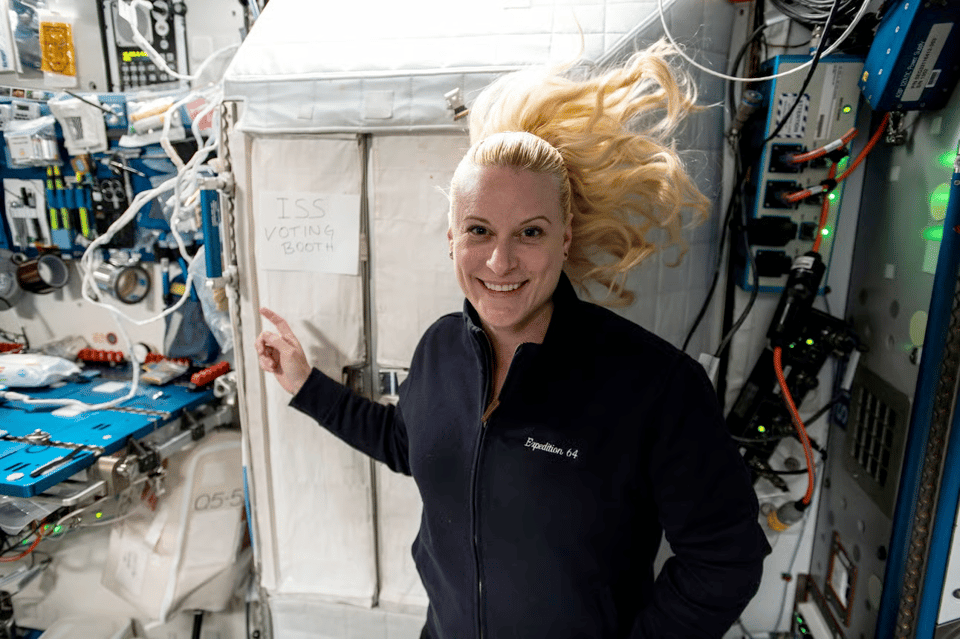

8) 🌌 Can astronauts vote from space?

As you’ve probably read, two astronauts — Butch Wilmore and Suni Williams — went up to the International Space Station for an eight-day day, but thanks to a malfunctioning Boeing spacecraft, they’re stuck there until next February.

That got Swapna Krishna, my favorite space blogger, wondering something. Wilmore and Williams are both US citizens, and there’s a presidential election in November. Are the astronauts allowed to vote while in outer space?

She contacted NASA to find out, and apparently — yep, they can. The astronauts live and work in Texas (at the Johnson Space Center in Houston) and in 1997 Texas passed a law allowing astronauts to vote.

It’s complicated, though, as Krisha writes …

NASA astronauts fill out the FPCA before they launch, and it’s approved by their local county election office. Once that happens, the county clerk sends a test ballot to Johnson Space Center in order to confirm it can be filled out on Space Station computers. Once that’s confirmed, NASA uplinks a secure electronic ballot to the ISS. The county clerk sends specific credentials to each crew member’s email so they can access the ballot. [snip]

After the astronaut on the ISS completes their ballot, it’s sent back to NASA through the Near Space Network, which is managed out of NASA Goddard in Maryland. It goes through a Tracking and Data Relay Satellite (or TDRSS) to White Sands Complex in New Mexico (yes, the same White Sands that Boeing Starliner will land at.) White Sands then transfers the completed secure ballots back to NASA’s Johnson Space Center. Finally, it’s sent to the county clerk who is the only one besides the astronauts with the password to decrypt the ballot.

A fun post overall — go check it out, and subscribe to Krishna’s feeds, which are great!

(That picture above is of astronaut Kate Rubin voting in 2020.)

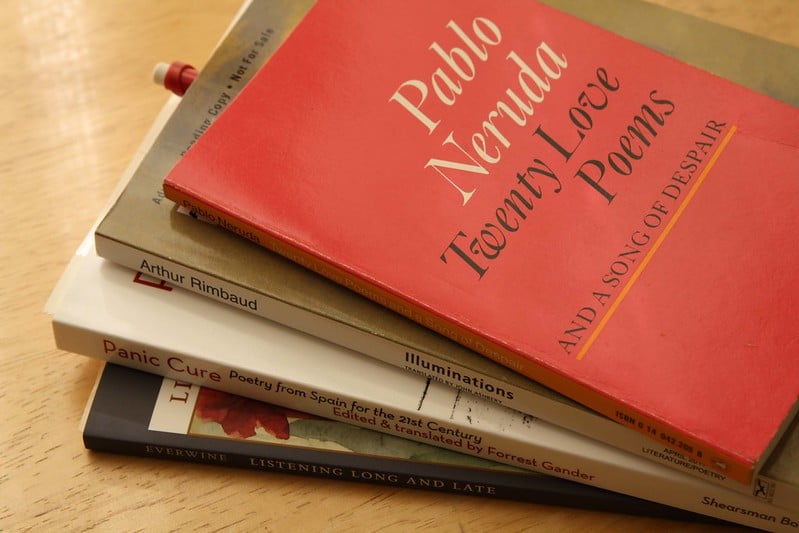

9) 🧠 The cognitive effects of memorizing poetry

Jacob Brogan has written a terrific essay about the mental effects of memorizing poetry.

A few months ago, while flying to see an old friend who was approaching death, he spent the flight memorizing Clive James’ “Sentenced To Life”. He found he so enjoyed the process — and the product; being able to summon a poem to mind at any instant — that he started memorizing another poem every week.

This is something I’ve written about myself. In an essay a year ago, I talked about how memorizing poems altered the way I see and absorb the world: “A memorized poem becomes part of the fabric of your thought, a tool that your mind constantly uses to make sense of the world.”

But Brogan addresses something different here — the fascinating way that the act of memorization changes how we experience the language of the poem …

Because the process is as simple as it is stultifying, memorizing a great poem always begins as a crime. The tedium of repetition reduces the hewn gemstone to a pile of gravel in which only the occasional dull agate stands out. But as you run your hands through the rock, the lines at last come together again, and the scattered text transforms back into a treasure, often a more valuable one than it was before. [snip]

When you are memorizing a poem, a similar kind of noticing begins at the level of form. Demolition reveals the joints that articulate a structure, the way every part supports up every other, and attention begins to give way to understanding: The three single-word lines that conclude Clare Cavanagh’s translation of “Transformation” — “lightning, / transformation, / you.” — expand and then contract, like an exhale followed by a sharp gasp at the unexpected appearance of a beautiful face. Because such details help to secure the poem in the mind, noticing them goes beyond the ordinary academic labor of close reading. You dissect the poem to graft it into yourself; in the process, its meanings become not objects to be discovered over there, on the page, like birds on a branch, but instead found here, within you, where the tree takes root.

It’s a really spectacular essay — go read the whole thing!

10) 🧭 How the seasons mess with your moral compass

We all know that seasons affect our mood — that’s where seasonal affective disorder comes from, after all. But a new study suggests that they can also affect our morality: Our sense of right and wrong.

A survey of 230,000 Americans over a decade found …

… that people embraced certain values — purity, loyalty, and respect for authority — more strongly in spring and fall, compared to summer and winter.

Psychologists call those “binding values” because they tend to promote social cohesion. They’re a double-edged sword, however: Their upside is that they increase cooperation among members of an in-group, but they can also increase prejudice against out-groups. (The study authors also investigated care and fairness, sometimes known as “individualizing values,” but found no consistent seasonal pattern there.)

The researchers also found that — again in the spring and fall — people’s “self-reported anxiety” rose. (There’s a good story about it in Vox by Sigal Samuel.)

What’s up with this? It’s pretty weird, as the study’s lead author Ian Holm notes, because while behavior is often considered to be malleable and amenable to transitory influences, morality usually isn’t.

Caveats: The study might not hold up; while it had lots of subjects, which is good, it wasn’t following the same people over time.

But if it’s legit, it’ll be interesting to figure out why seasons would tweak our morality. Possibly summer lowers anxiety because of the sun? But how would fall increase “binding values?” No-one really knows. But go give the story a read; the original study is free here.

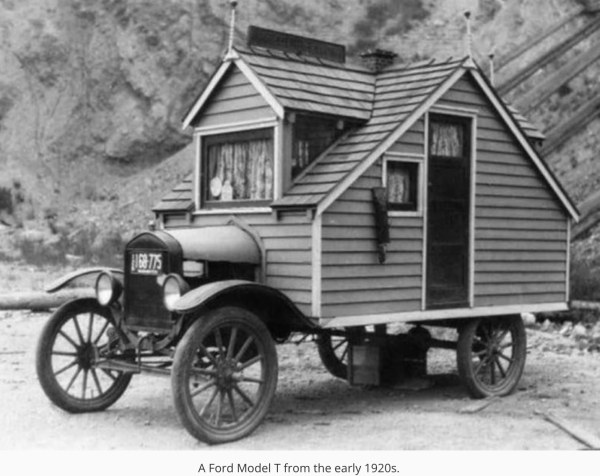

11) ⛺ Glamping in 1920

Cars were the hot new technology in the 1920s, and apparently inventors immediately starting building full-on houses on wheels.

Via Matthew Ingram’s “When The Going Gets Weird” newsletter, I found this Book of Joe post with a wonderful gallery of the cars — go check it out!

I really love the wit with which many of these were built. Some are clearly functional: They’re proto-vans, or proto-mobile-homes. In the minds of their inventors, you can see the light bulb go on — so early in the automotive age — that huh wow we could kind of go live anywhere.

But with other of these vehicles, like the one shown above, it’s more like funny projects, a sort of visual joke about the idea of a mobile home.

12) 🦨 Machine learning that IDs a wild animal by its paw prints

If you want to preserve a form of wildlife — say, the hyena — you need to know how many of them there are, and where they live. For decades conservationists have tried to do that by leaving automated cameras around forests, hoping they’ll snap pics of elusive beasts. But cameras aren’t terribly reliable, because animals may not walk near them. (Sometimes, like hyenas, they’ll destroy them.)

But a nonprofit conservationist group called WildTrack has developed a new idea: They take pictures of animal tracks and use machine learning to identify animals by their pawprints.

Cool! But it gets even cooler, as Ryan Truscott writes in The Atlantic …

But the WildTrack team’s goal is to produce more fine-grained assessments—teaching their machine-learning system to identify which individual animal left which print.

For the past five months, Lemerle has been building up a reference library of hyena tracks for WildTrack’s training data sets. Each time she finds a clear hyena footprint at Baker’s Bay, a breeding ground for Cape fur seals on Namibia’s Atlantic coast, where brown hyenas come to hunt, Lemerle reaches for the 30-centimeter ruler in her backpack, lays it on the sand beside the print, and takes a photograph with her smartphone.

Then the WildTrack team, headquartered at North Carolina’s Duke University, analyzes the footprint’s size and shape in intricate detail. They break each print into 120 different measurements, which the machine-learning software can compare with others in the database to look for a match. Sometimes, Jewell says, all they need to tell hyenas apart are subtle differences in the angles between their toes. [snip]

[The animal prints show] grisly injuries: shredded ears, gashed necks, and occasionally a severed foot. Some hyenas limp with broken legs. “If each individual has a different limp, that probably has to show somehow on their tracks,” Lemerle says.

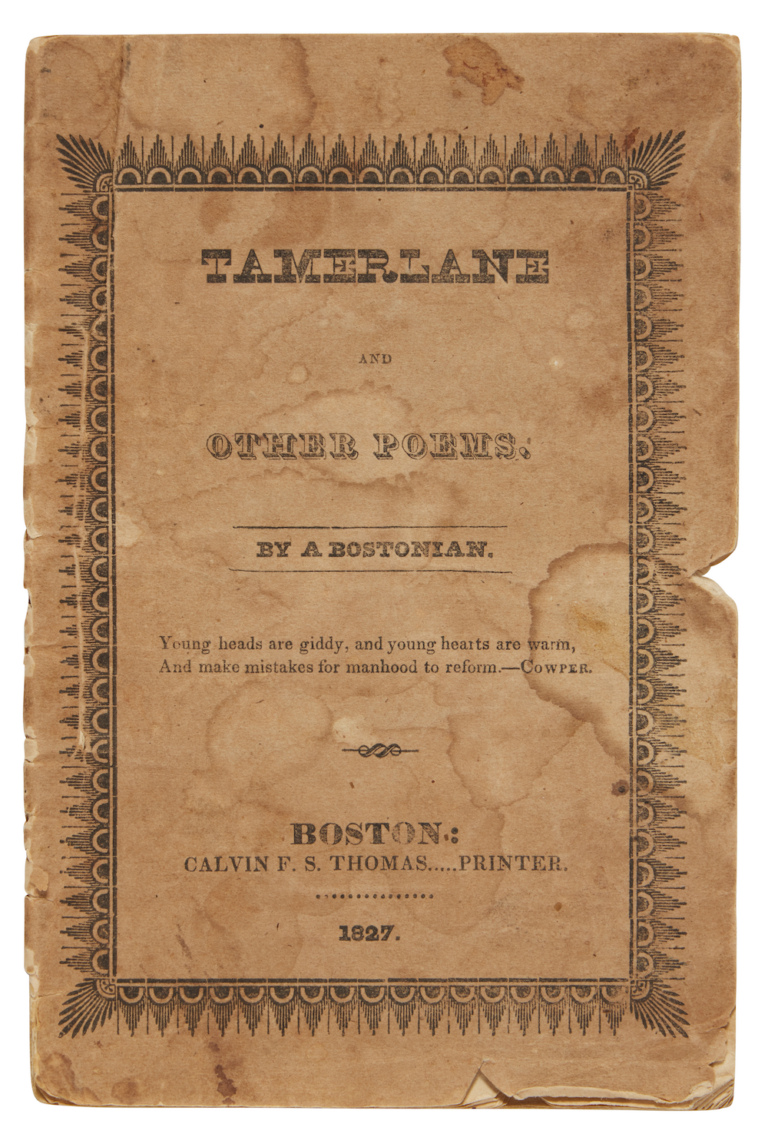

13) 📖 On the hunt for the rarest book in American literature

At age 18, Edgar Allan Poe paid a Boston publisher to print an estimated 40 copies of Tamerlane and Other Poems, his debut collection. The print job was lousy, with weak binding and a hodgepodge of fonts on the title page. Nobody reviewed it, and almost no-one bought it.

But since Poe went on to become a titan of early American literature, that chapbook is now incredibly valuable — because it’s incredibly rare. Only twelve copies are known to exist. The Library of Congress doesn’t even have one.

Bradford Murrow wrote a fun essay in which he attempts to personally visit, and view, as many copies as he can. (It was research: He wrote a novel the plot of which revolves around someone forging a thirteenth copy of Tamerlane.)

My fave moment is when he visits Susan Jaffe Tane, who owns one:

Just five Tamerlanes are complete with their original wrappers and Tane’s is one of them. It’s safe to say that hers is easily the most recognizable, with a prominent ring stain on its front wrapper, the result of somebody having used it as a coaster for their wet glass (of whiskey, I like to imagine). This inadvertent bit of vandalism is now hard to imagine. But Tamerlane wasn’t widely known beyond Poe specialists until the writer Vincent Starrett published an article in a 1925 issue of the Saturday Evening Post. “Have You a Tamerlane in Your Attic?” instantly raised the public’s awareness of the book’s significance, rarity, and value. Starrett’s column is credited with precipitating the discovery of some five previously unknown copies.

Could our thirsty vandal have made their mark, so to say, before “Attic” came out? Or maybe never read it? Either way, Tane’s copy was discovered in 1988 in a bin of old farming pamphlets at an antique shop in Hampton, New Hampshire, when a vigilant collector bought it for $15 and resold the book, which then made its circuitous way through Sotheby’s, where she acquired it in 1991. An online search today for “Poe Tamerlane” will bring up the distinctive Tane copy on multiple sites.

You can read an 1884 reprint of the book scanned here at the Internet Archive.

14) 🧮 A final, sudden-death round of reading material

Doom on a fleshlight. 🧮 Auto-tuning a kazoo. 🧮 How writing diaries changed history. 🧮 A guitar pedal with six axis of control. 🧮 AI that reconstructs brain signals to show what you’re looking at. 🧮 “Microretirement". 🧮 Virginia Woolf’s most savage insults. 🧮 Origami-flower-folding machine. 🧮 The roof-top-solar revolution in Pakistan. 🧮 3D-printable clicky fidget keychain. 🧮 Using the Raspberry Pi 5 as a desktop computer. 🧮 “Song Pong”. 🧮 3D-printable rubber-band boat. 🧮 “I know someone who literally takes garbage bags full of $20s with him back home.” 🧮 The age of weird Arctic research. 🧮 Murder confession found inside a house’s wall. 🧮 Wind-powered transatlantic shipping. 🧮 The first-ever image to be Photoshopped. 🧮 Smell-o-vision lives. 🧮 How a storm made Britain’s tea worse. 🧮 A trade dispute over whether lobsters crawl or swim. 🧮 “Ropeless” fishing. 🧮 Saxophone that changes color with every note. 🧮 Ozempic-pen hacking. 🧮 Cops are starting to go for Teslas. 🧮 5,000-year old “Stonehenge” formation found at bottom of US lake. 🧮 The first ever piece of slash fiction. 🧮 “Null Island.”

CODA ON SOURCING: I read a ton of blogs and sites every week to find the material for the Linkfest. A few I relied on this week include Hackaday, UnDark and Mathew Ingram’s “When The Going Get Weird”; check ‘em out!