How I Study (Across the Seas 2020 #15)

Hello readers!

Let’s talk research tools. It’s a subject near and dear to my heart, and although I’m a long way from being able to do things as well as I’d like—because literally nothing solves all my problems, and I’ve found it so frustrating that I’m building my own tools as a result, slow though the process be—I think it’s still useful to share the ways I approach the process. (And yes, I’m actually back at it this week! Thanks to those of you who wrote kind notes in response to my note that my wife had dealt with COVID-19.)

Before I get into the nitty-gritty details, the usual qualifiers: what this is, who I am, and how you can escape the infinite list of newsletters that is 2020 if you so desire—

- This is Across the Sundering Seas, a usually-weekly dive into the things I’ve been reading and studying, or (like this week) occasionally riffs on the process of studying itself.

- I’m Chris Krycho, currently a software engineer at LinkedIn, with formal education in physics and theology, and an unending well of nerdiness and pedantry in equal measure.

- The escape hatch is right here, always. If this newsletter isn’t doing it for you, eject!

Okay, now: how I study these days. The workflow isn’t great, but it’s getting the job done. It’s a combination of reading materials and a set of note-taking tools.

Reading materials: mostly books. I read books. I think reading books is helpful in ways that reading the internet isn’t (even though I do a lot of that, too, of course). This year’s reading is a good mix of non-fiction and fiction, and I’m finding Winning Slowly Season 8 to be a fabulous forcing function. Deadlines for actually finishing books, and having to be able to talk intelligently about them for over an hour, are both great tools for making me both read and think as I go. This is, I think, what makes college and grad school work so well (when they work well): at their best, they’re just excellent forcing functions for engaging with material and then being accountable for that material in a context where other people will help you (and you them) understand it better. I’ve joked that this process is just my way of doing a graduate seminar in a bunch of the texts on tech ethics… but the thing is: it’s not actually a joke.

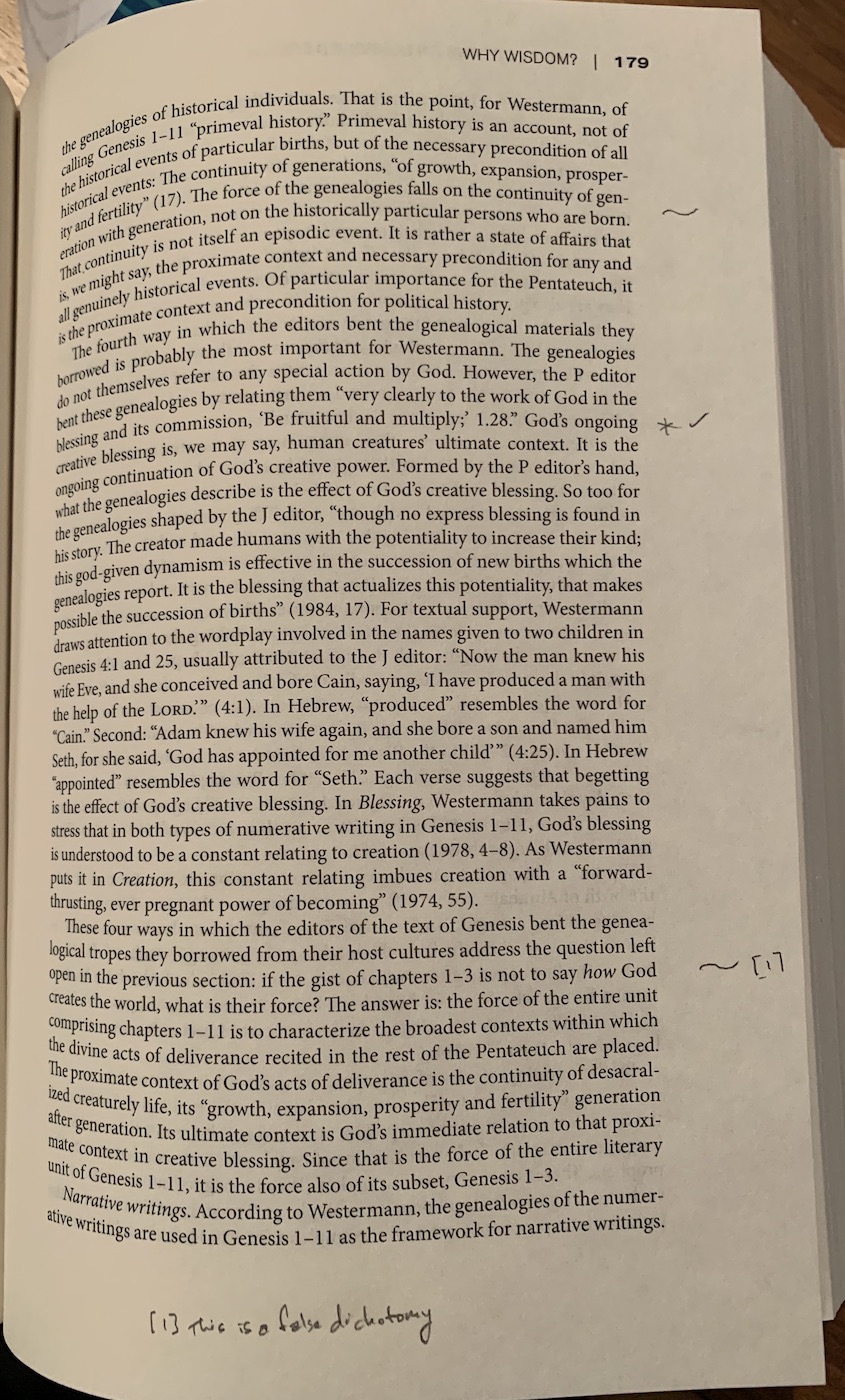

I read books with a pencil near to hand. I don’t usually write a lot of notes in my books anymore. I’ve tried it in the past, and it didn’t quite gel for me. Instead, I just make marks that signal various sentiment about the book, and which I can use in reviewing the text later:

- a star to indicate something is central to the argument

- a check-mark to indicate something I agree with

- an ‘x’ to indicate something I disagree with

- a tilde ‘~’ to indicate something that I think is important enough to call out but which I neither fully agree nor fully disagree with

- exclamation points to emphasize any of the above, especially agreement or disagreement

Very occasionally, I will add to these actual notes on the page—usually only if it’s something I want to make sure to remember, don’t want to switch to a digital device for notes (more on that below), and think is important enough to call out specifically.

These marks make it easy for me to go back and review the text at a high level without rereading the whole thing. That process of review is, in my experience, extremely helpful in actually comprehending a text and thereby growing intellectually—whether through agreement or disagreement! Not every book deserves it, though. For the books I’ve been reading for the podcast, I usually skim back through these. For the reading I do when prepping for teaching a Sunday School class, I go back through them in detail. If I find on finishing a book that it didn’t even warrant that kind of review, I won’t bother. A thoroughly marked-up page in a book I’m reading might look like this:

Sometimes I’ll simply leave it at that: having noted the points and possibly reviewed them, I’ll move on. However, if I found various notes in the book particularly illuminating, or if I need to be able to reference them later (for teaching, for example), I’ll transfer them into my notes system. At this point, I do all of that in Bear, because it makes it straightforward and simple for me to link between notes, group them via various (often overlapping) tags, and ultimately build up a Zettelkasten -style notes system. When I go to build a lecture (or, as I ever aspire to, an essay), this makes it easy to pull together not only the things I’ve been thinking on a subject but also the most helpful things I’ve found from others on a subject.

(Aside: I’ve also been learning this year to put books aside partially read if I’ve gotten the value I need out of them. As a lifelong completionist up to this point, this has been… hard for me. It’s a valuable skill, though: sometimes a book has an interesting chapter or two; that doesn’t mean you have to read the whole thing. As a prime example, I’ve been going through our church’s training for lay leaders (elders and deacons for those of you in the know), and we were assigned sections from two books for our reading. I read those sections, but I don’t expect to touch the books again, and I don’t expect to read any of the rest of the material in them. It’s not that they’re bad books, it’s just that my docket is full; I don’t have time to read everything front to back unless doing so has specific value.)

Traditionally, transferring quotes to my digital notebook has been the most laborious part of my study process. When writing papers in seminary, this often took as long as the work of actually doing the reading or outlining itself. That’s not especially useful work, either: copying has some value in helping cement an idea in my mind, but I find that review and rereading does that much more effectively. Accordingly, I was delighted when I stumbled across Prizmo Go, an iOS and iPadOS app which does fantastic OCR. It’s as simple as taking a picture of a book and copying out the text. (You can see a video clip of this process with an actual note I copied from a book here.)

I copy that into Bear in my normal note format as a quote, assign it the BibLaTeX identifier I set for the book I’m using, and tag it with the author and other subjects. For the item I show capturing in the video linked above, the resulting note’s content looked like this:

2020.04.11.2035 the relation between Creator and creation > The relation between Creator and creation is thus expressly not one of begetting. @kelsey:eccentric:vol-1, 178 # z/authors/David H. Kelsey# #z/theology/creation

From there, I can navigate to every single note I have on creation, as well as every quote from Kelsey (in this book or any other source), and I also have a quick reference back to the location in the book so that I can go get more context again later if I need it (at least when I still have the book).

I then try to work back through my notes every so often. This is the least disciplined part of my process so far, and the part that could use the most improvement. It is usually just in reviewing notes I have taken, and mulling on them and following connections between them that I end up finding the best ways to say things I want to say—in blog posts, in this newsletter, in the essays I do manage to finish every few years. I think a very profitable change here would for me to have my digital notebook open to a given subject at the same time as I have a physical notebook open for sketching out ideas and outlines for writing. Something to try soon.

Thanks for reading, and I hope this was a helpful bit of insight into my process!