A rat scurries across your path as you walk out of the subway station at night. A cockroach emerges from underneath your bathroom sink when you go to brush your teeth. A flock of pigeons descend upon your cracked-open window.

Did you feel yourself squirm when you read these statements? Did your eyebrows rise, your nose wrinkle, your stomach churn?

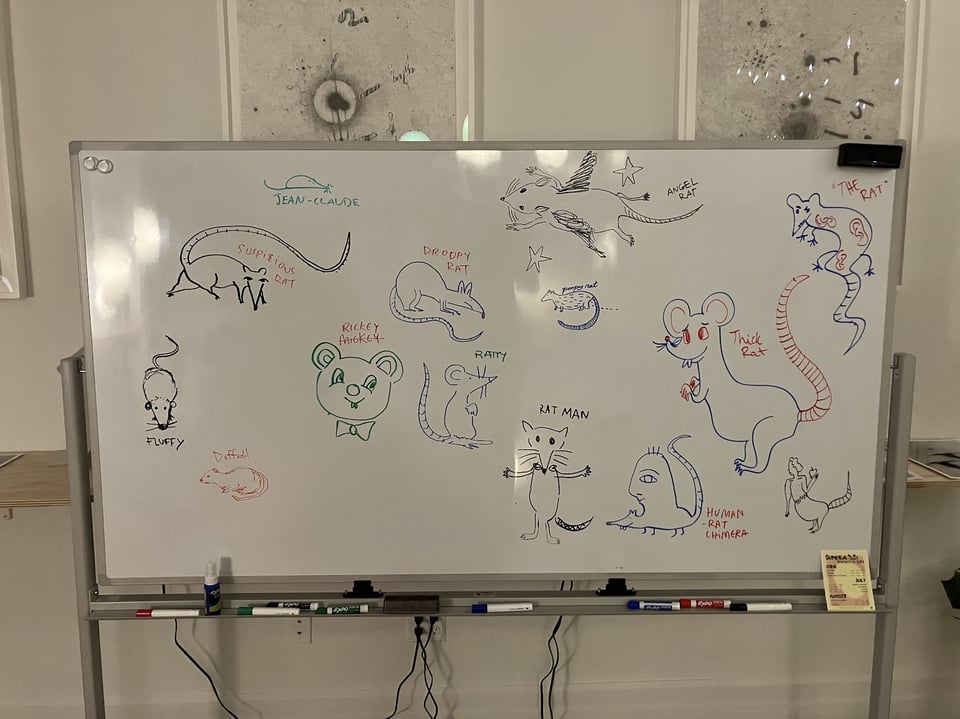

In June, Chimeras Collective wrapped up a seminar at the Strother School of Radical Attention, CREATURES, in which we asked these exact questions. By studying rats, pigeons, and cockroaches, we explored how disgust colors our relationship to urban creatures. Attention, here, allows us to examine why we tend to be disgusted by urban pests — and whether we can turn said disgust into fascination.

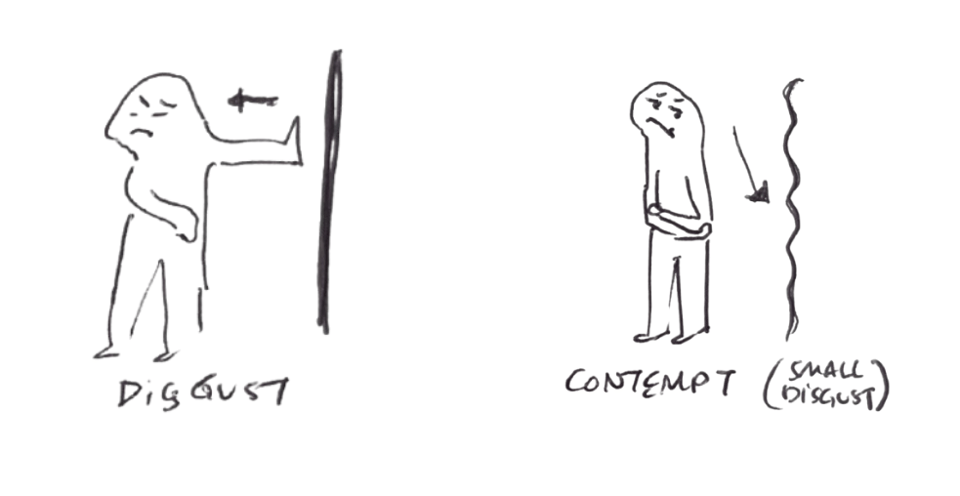

Disgust is a complex sentiment, typically marked by declarations or expressions of the object as revolting, repulsive, or abhorrent. It’s urgent and specific; it places demands upon the subject (ourselves) to be rid of the object, somehow. Above all, it is an expression of intolerance. The disgusting object cannot stand.

Certainly, disgust has its roots in instinctual behavior. Charles Darwin himself believed it to serve an evolutionary purpose as a warning of health hazards. As an emotion primarily associated with the oral, disgust emerges commonly through emphatic expressions of distaste. What is disgust saying, to both ourselves and to others? In part, get that shit away from my mouth, now.

But disgust is also a socially learned emotion, rarely so simple as an instinctual expression. In Anatomy of Disgust, theorist William Ian Butler asserts that “above all, it is a moral and social sentiment. It plays a motivating and confirming role in moral judgment in a particular way that has little if any connection with ideas of oral incorporation. It ranks people and things in a kind of cosmic ordering.” In this way, disgust is trained. We learn to discern the disgusting at a young age from teachers of social culture & morality: mothers, schooling, religion.

What have you labeled as disgusting, recently? Perhaps it was a potential disease vector like rotting meat, but there’s a good chance that you ended up naming something entirely distanced from the oral. Maybe it was the weather for being unbearably hot and humid. Maybe your neighbor who catcalls women as they walk by. Maybe a politician clearly acting out of hatred and self preservation.

With pests and vermin, such as the subjects of our seminar, our disgust response most commonly includes both the instinctual and socially learned. In class, we asked: how did these creatures come to be labeled as pests (hint: not so straightforwardly!)? What are cultural examples of honoring or even worshipping these creatures that we spend millions to exterminate? How does embodying a being we most frequently ignore build our capacity for empathy with our nonhuman neighbors? Ultimately, the label of pest is a social construct, but one that was constructed for a reason — these are creatures that can eat our food, transmit diseases (though perhaps not as often as we are led to believe), and defile our homes.

In class, we never intended to get rid of the disgust response, but instead desired to complicate it. It’s our way of staying with the trouble, as Donna Haraway puts it. Attention is a tool that brings us closer to, rather than distances ourselves from, the nonhumans we see daily. Disgust tends to wall us off from curiosity, connection, and understanding. By troubling it, we begin to see fascination take its place.

In NYC, kinship with the more-than-human can feel idealistically located in some “other” place — the capital N Nature that always exists outside the city, outside the quotidian. But nature is all around us, all the time, even in the concrete jungle. This seminar brings our attention to some of the stars of our urban ecology, because the creatures of NYC aren’t going anywhere, and living well in relationship to this land must entail examining our relationship with our nonhuman neighbors. In class, assignments and practices brought attention to how these creatures show up in our lives, from tasking students to find and send pictures of rat roadkill to running around outside to act like pigeons (scaring some tourists along the way). So what did we learn?

With cockroaches, we engaged the literary, reading excerpts of Clarice Lispector’s Passion According to G.H. while attending to our own responses to the G.H.’s identification with, and eventual consumption of, a dead cockroach. Following that, we did our own experiment with a two-year-old cockroach-in-a-jar that Olivia had been saving. One student even ended up taking a bite of the roach! An important part of this class was attending to our own different thresholds for disgust. While the student seemed to have no qualms with biting into the roach, I found myself fighting my own urge to gag. In class, the intention was never to compete with one another for “least disgusted,” but in noticing our differential responses to a dead roach, we can recognize how disgust comes from a series of social, cultural, and physiological factors that may remain mysterious to us.

For pigeons, we followed a lesson on pigeon history and anatomy by transforming ourselves into pigeons. With pita bread in hand, we descended upon the tourist-riddled streets of Dumbo in search of pigeon friends (who are surprisingly difficult to find there in the evening). One might have thought that the pigeons would be all over us and our plentiful free bread, but in reality the few we found were reluctant to feed — owing to it being in the evening (not their usual feeding time), suspicion of our intentions (we were seeming awfully desperate), or something else. One intriguing observation from going about our exercise was just how differently the shape of pathmaking is between pigeons and humans. In the city we so frequently are moving in straight lines, tracing grids. But pigeons operate in arcs and circles — what would it mean to spend an entire day moving like a pigeon? Bucking the grid, returning to the same spots after being spooked by a distant bird of prey?

CREATURES ended with rats — perhaps NYC’s most iconic vermin. As with all constructions of the label pest, our relationship with rats is deeply entangled with colonialism. It was colonial trade that brought the brown rat (which, by the way, is not always brown in color) to be found nearly everywhere in the world, with the exception of Alberta, famous for its strict yet effective rat eradication policies. In Vietnam, French colonial rat bounties, measured by rat tails, led to a thriving rat breeding industry among locals, and a Hanoi full of tailless rats running around. In Indonesia, Dutch colonial doctors ordered the destruction of over a million traditional homes out of a conviction that bamboo walls were perfect rat homes. It’s hardly surprising, given the tenacity of rats to avoid humanity’s continual efforts at eradication, that the attempt failed, causing only to damage the local economy and force debt upon the local population who had to buy timber from Dutch corporations. Rats, like pigeons, cockroaches, and other pests have constantly been thwarting the ardently sought-after control that characterizes modernity. Throwing sand in the face of colonial control policies, they forge an uneasy interspecies alliance with those resisting domination.

Throughout class, we continued to ask: how might we live well with these creatures? In doing so, we have to acknowledge that they are, indeed, pests that disrupt our way of living and disproportionately impact the impoverished. Yet alternative ways of being-with the nonhuman are possible, and possible right here in NYC. We see it already with the internet’s fascination with pizza rat, and the success of PigeonFest at the high line. In class, we explored a few of these frames: we might commemorate our pests, honor them, worship them, eat them, give them jobs, create altars for them, talk to them, listen to them, act like them, feed them, make them a playground, or play with them.

Pests and vermin are an important part of how we socially enforce the boundaries between culture and nature, between us and them. But if we devote our attention to the creatures all around us, we begin to notice just how porous those boundaries are. Nature is here, it’s in our walls and on our sidewalks and in our trash bins. This concept is intrinsic to Chimeras Collective, because the chimera, too, is a boundary-blurring figure. Attention, ritual, embodiment, study, and science are all tools that lead us to a stronger kinship with our urban neighbors — both human and nonhuman. Rats, pigeons, cockroaches: these creatures can be sources of wonder, if we let them!

kyle 𓆏 of chimeras collective

PS: Chimeras Collective is pausing programming for August as we’ll be away from NYC exploring some ecologies out west. But we’ll be back with a suite of interspecies gatherings come September/October – if you’d like to partake/collaborate, or if you have a project of your own that could benefit from some chimeric influence, please let us know!

You just read issue #2 of Chimeras Collective. You can also browse the full archives of this newsletter.