We Should All Be Archivists

Lately, I keep obsessing about two seemingly opposing but interrelated trends: 1) The past decade has seen an incredible bounty of art and self-expression from marginalized folks, including BIPOC folks, queers, disabled peeps and others. 2) We’re in the middle of a huge, well-funded backlash against those same marginalized folks, with the goal of driving us out of public life.

I’ve loved so much of the art, culture, criticism and reporting that I’ve seen from marginalized people in the past several years, and I’m terrified that a lot of it could be buried in this tidal wave of hate. We’re really going to need all of those stories and creations to hold onto, during the dark times to come. We’ll keep producing great art and culture no matter what, but we’ll still want to hold on to the proof of what we can accomplish when the “mainstream” culture industry gives us access to resources. And there are so many obscure, little-noticed, indie projects from the past several years that we’re going to want to revisit. This has been a fertile time, and we need to save as much of these riches as we can.

The good news? There’s something you can do to help. You can become a citizen archivist. To find out more, I talked to Isaac Fellman, an archivist with the GLBT Historical Society and author of Dead Collections and the upcoming Notes From a Regicide. (Dead Collections is a beautiful novel about a trans vampire who works in an archive. It’s essential reading!)

Note: The following conversation has been condensed and edited.

I've been thinking about the fact that in the past there have been times when marginalized people, including queer people, produced a lot of amazing writing and art, and then a lot of it was destroyed in the middle of a violent backlash. Can you walk me through what happened, and how it happened?

The first thing that you think of is [Magnus] Hirschfeld's archives. Hirschfeld became a worldwide celebrity for quite a while. He was traveling the world doing lectures. His Institute of Sexology was seen as this really exciting, forward-looking thing, and we had this moment of optimism.

We had a — I don't want to say the phrase 'transgender tipping point' — but it happens again and again. There is a step forward, people notice, and visibility becomes a danger. And then then there is backlash, and in the most extreme cases, the literal burning of his archives.

I grew up not being aware that trans people had existed in history, but also not knowing much about the countless other marginalized people who had fought and created amazing stuff. It just feels as though there's an effort to forget anything that deviates from the “mainstream” narrative. Why are people so good at burying the past?

Yeah, I think about this a lot. We do it for a lot of reasons. And different people in different cultural positions do it for different reasons.

I think for the dominant culture, it's very easy to forget. Because you don't want to think of yourself, or people like you, as someone who could have spoken like this and done these things. I think about how many people my age were very comfortable using 'gay' as an insult, many of whom would rather forget that they ever did that.

I think it's also it's easy to forget activist histories if you are telling mainstream history. The dominant culture always sort of has a vested interest in pretending that activists didn't do this [work] and instead sort of saying, 'Well, the government realized that people should have more rights. So [it] gave them to them.'

But lastly, the sort of version of forgetting that I think about most often as an archivist at a queer archive is just simply the ways that trauma makes queer people forget things, just to ensure self-defense. People live with the scars of anything from having their coming out and transitions delayed to religious trauma. And losing friends and family to death or to rejection. Sometimes just to go on living, you have to focus on the day-to-day and going forward. And sometimes that means that things slip away.

I have different levels and kinds of sympathy for the reasons that people forget, but I think that forgetting is really the shadow side of history. It forms this negative space.

So you're basically saying that a lot of marginalized people's achievements from the past get pushed under the rug because of people are burying trauma, and everything else gets buried along with the trauma?

I think that's a big part of it. You know, I often have donors of archival materials say to me, 'I was going through my old stuff and I thought to myself, I really did that, didn't I? That was me.' And, you know, often these are really significant achievements, but because there's so much pain around them, it's hard to give yourself credit for the person that you've been.

What makes for a good archive? What makes an archive robust against accidental or deliberate destruction?

I have a few different answers to that one. One of which is that simple physical preservation is very important. The rule of thumb is that if you have materials, they're comfortable where people are comfortable. If it's at all possible, keep your materials out of the attic where it's hot or the basement where it's damp. Because it doesn't take long for materials to age. For archiving at home, use plastic tubs, cardboard boxes, anything that keeps the dust and the bugs out.

Another important answer is, archives have a long tradition of not wanting redundancy, and saying, 'We don't want just a copy of something another archive has. We don't want to collect things that aren't unique.' And I think that that is something that needs to change. There is a cute acronym that we use to talk about digital archiving specifically: LOCKSS. "Lots Of Copies Keeps Stuff Safe." So we need to start expanding that vision into like redundancy of collecting materials across archives that are professionalized — and across private archives too, like the personal archives that people have.

There's a really long tradition of trans people forming personal archives, and I would like to see more of that actually.

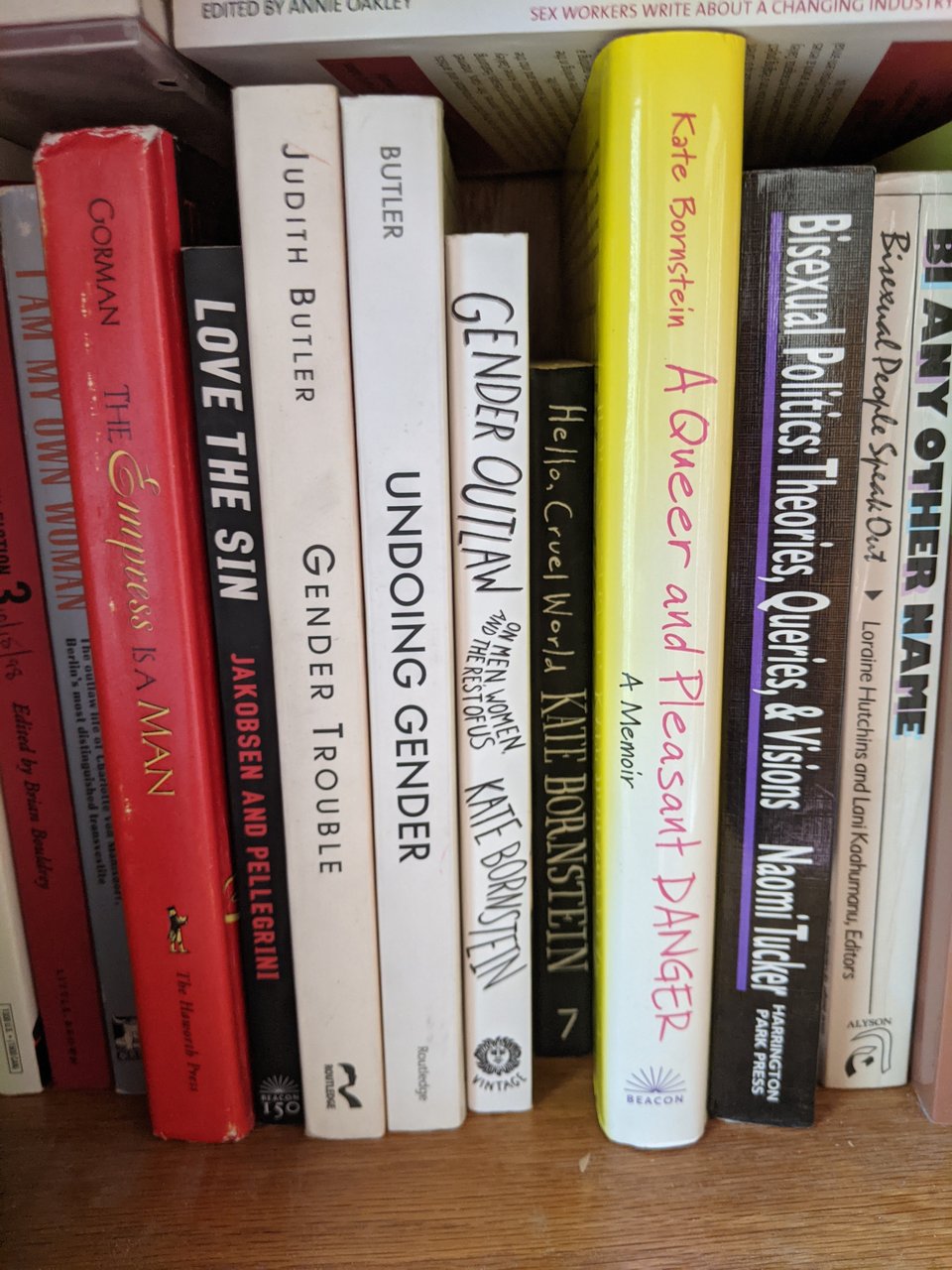

I was about to ask you about that! I feel like we should all be citizen archivists, especially those of us who've been around for a little while, and have just accrued stuff. Like, I have a bunch of queer books from the early 2000s which now are hard to find. And zines, and just random crap.

In the field we would refer to that as 'ephemera,' but 'random crap' is accurate as well.

So what does it mean to be a citizen archivist?

I think of the examples of people whose collections are now part of our archives at the GLBT Historical Society. Two of my favorite citizen archivists are Francine Logandice, who was a trans woman nightlife entrepreneur. She owned a bunch of bars in San Francisco and the Russian River, and she poured a lot of the money she made from that into a really incredible collection of trans ephemera and books. Everything from these dense sexological texts to small press porn to lots of mainstream books about figures that she suspected were trans but who weren't talked about in that context — like, she was very interested in George Sand.

I also think about Lou Sullivan and his intense collecting on contemporary trans topics. His collecting of medical research and studies, and materials on his favorite historical figure, Jack B. Garland. And the way that his diary, which he kept for for thirty years of his life, is itself sort of an archive of his emotional, romantic and sexual life as a gay trans man.

The thing that figures like this have in common is a recognition of their own importance, and of the importance of their things. When people ask me for advice about queer archiving, I usually say that the most important thing is to recognize your importance. You need to see yourself as a as a repository of history — as a repository of memories, both internal and external, and in the things you care about. Our archives are reflections of our interests, our obsessions, our private concerns. No two people collect alike, and the shape of your brain is memorialized in many ways by the things that you collect.

I love that.

Thank you. Yeah, we should all be archivists. Whether the end goal of our collecting is for our materials to stay with us or with our heirs, or whether you're ultimately hoping to donate to a larger archive that can make your materials more public.

So let's go back to ephemera. Because when I look back at the past ten years, specifically, there's been so much: TV shows, movies, podcasts, music, fan art, fanfic. There's been tons of digital stuff as well as books and physical objects. There's been so much great television, and it breaks my heart to realize that TV shows are not being preserved the way they should be. So can you talk about having a digital archive?

Yes, it's very important to recognize that digital material is not forever. I think people have really started recognizing this in large numbers, because we're starting to get to a point where people are trying to use things from their own personal archives and histories that are from fifteen years ago and they're finding like, wow, the, the way that this file is [unusable.] We have AVI files that were made as masters in 2013 or 2015. And I have contemporary documentarians who are like, 'Isaac, I can't open this in my regular software, and when I do manage to open it there's a high whine in the background.' And I'm like, 'Oh god, that's the master.'

The other day I was looking for video of an event that I performed at in the early 2000s, and it was a RealVideo file.

I'm sure it looks like you were trapped in one of the books in Myst.

So yeah, archivists are definitely starting to think about digital archives in a more serious way. The period of quarantine was really a wake-up call for us, because suddenly we were all digital archivists. We were trying to do our work from home and recognizing the limits of digital archives. We have a DAMS now: a Digital Asset Management System that's designed to preserve and back up digital files in a stable way in the cloud.

The larger question that we haven't reckoned with is how to make things still legible in the future and in all honesty, this is another thing that trans people are really good at. We had a trans volunteer who was a brilliant digital preservationist, and one of her projects at the GLBTHS was preserving one of the first trans websites, TGForum. She set a thing up with the Internet Archive, with a Mac emulator that will allow you to experience it like you would have in 1998.

It's good that people are starting to think about digital ephemera. Like memes! I feel like memes should be preserved.

Memes should be preserved. They're so important.

You already kind of answered this when you talked about, Francine Logandice and Lou Sullivan, but further back in history, are there any like success stories that you can point to of people preserving a lot of stuff that otherwise would have been lost?

Yeah, I can talk about José Sarria — an outsized San Francisco personality. His archive is absolutely huge. It's maybe 130 document boxes, that are six inches wide, so maybe 70 feet of stuff.

It contains his personal archive, of course. We've got his performance photos. We've got the scripts from his operas that he would perform — full-length gay parodies of operas. But he also collected everything that ever came his way, which was pretty much everything about the Imperial Court system which he founded. And all of these queer local fraternal orders, more or less.

So you don't just find out about the San Francisco Bay Area, you also find out about smaller towns, and places that were not thought of as queer meccas. You could look at the coronation booklets for each year's big blowout gala, and see: On the peninsula in 1987, who was the insurance agent who was friendly with queer people? You would get a sense of how the communities worked, and where they were shopping, and how they were conducting their day-to-day lives. You know, the ads tell you much, along with a detailed list of everyone who was anyone in queer community there.

When we were founded, one of the things that people were talking about was, 'We've got to do it for ourselves. There is not really a place for us yet in academia. This history is being done in a grassroots fashion from the ground up.' Basically, our first collection was a pool of different people's periodical collections that were kept in their living rooms.

Music I Love Right Now

I sometimes search for Amp Fiddler on Bandcamp to see if he’s released any new music — because I’ve loved everything he’s released in recent years. And… somehow I missed that he passed away, back in December 2023. Sigh. I’m really upset that i didn’t know this. Also, I had all these daydreams of meeting him, because I had a funny story to tell him about how his music came up in an unexpected context. And because he was amazing.

Joseph “Amp” Fiddler was a crucial part of George Clinton and the P-Funk All Stars starting in the late 1980s, and also a key player in the Detroit music scene. He probably played on a lot of your favorite albums. With Respect, the album he and his brother collaborated on in 1991, remains in heavy rotation on my music player. But starting in the early 2000s, he put out a slew of records that play with funk, hip hop, electronica and jazz, with some really startling results. I love his whole discography.

If you want to get started with his music, my plug is his album Motor City Booty, on Midnight Riot records, featuring frequent collaborators Dames Brown. You can get it on Bandcamp for pretty cheap right now. Just watch this:

TV I Love Right Now

I get kind of tired of the same handful of TV shows getting talked about endlessly, when there are so many riches right now. So on that note…

I got a subscription to AMC Plus so I could watch the (amazing) new season of Interview With the Vampire. I was looking for other stuff to watch on the service, and I stumbled on a show I’d never heard of called Domino Day: Lone Witch. As the title suggests, it’s the story of a witch named Domino Day in Manchester, England, who has an unfortunate need to drain the life essence out of random dudes. (Like a succubus, kind of.) And there’s a local coven watching her and trying to figure out what to do with her, because witches aren’t supposed to operate alone. It’s a gorgeous, atmospheric, dark show with a flawed character that you can’t stop watching and rooting for. It delves into themes of power, control and marginalization that feel super relevant right now. (Creator Lauren Sequeira says it was inspired by Buffy, Charmed and True Blood.) I’ve only watched the first couple episodes so far, but I’m loving it.

My Stuff

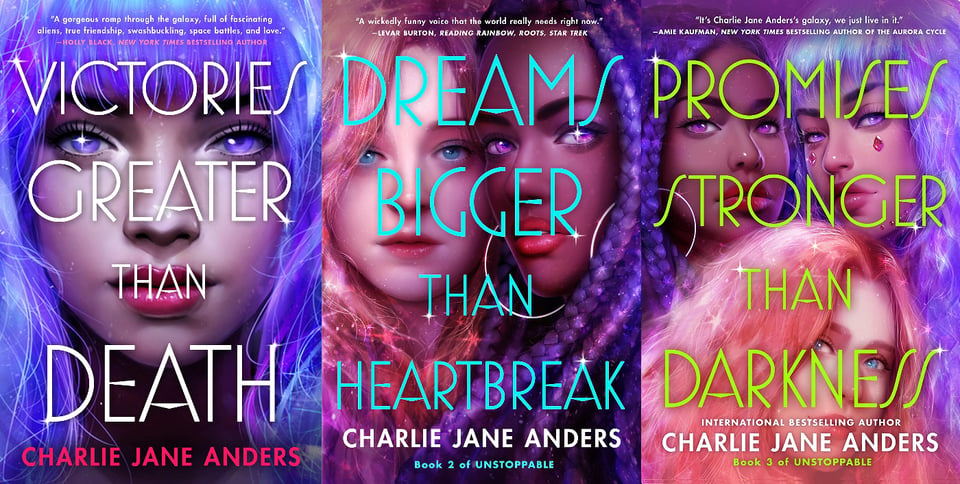

My novel Promises Stronger Than Darkness just won the Locus Award for best young adult novel! This means all three books in the Unstoppable trilogy have won the Locus Award for Best YA, which feels pretty incredible. The whole trilogy is out in paperback. Promises Stronger Than Darkness is also nominated for a Lodestar Award, so if you are a Hugo Awards voter, you can get the whole trilogy in your voter packet…

The newest episode of Our Opinions Are Correct is about the Planet of the Apes series, and we talk to Josh Friedman, writer of Kingdom of the Planet of the Apes.

This Saturday I’m co-hosting another Trans Nerd Meet Up, for anyone who self-identifies as trans/non-binary/genderqueer/gnc/etc., and who likes to geek out about whatever. No gatekeeping! We’re meeting at the Biergarten in Hayes Valley starting around 1 PM.

I’m going to be at Readercon in Quincy, MA, in mid-July! And then I’ll be at the Celsius Fest in Spain.

You can check out all my book review columns in the Washington Post.

I also have some other books! There’s New Mutants Vol. 4 and New Mutants: Lethal Legion. Not to mention my writing advice book Never Say You Can't Survive and my short story collection Even Greater Mistakes!