This Queer Actor Scandalized 1730s London

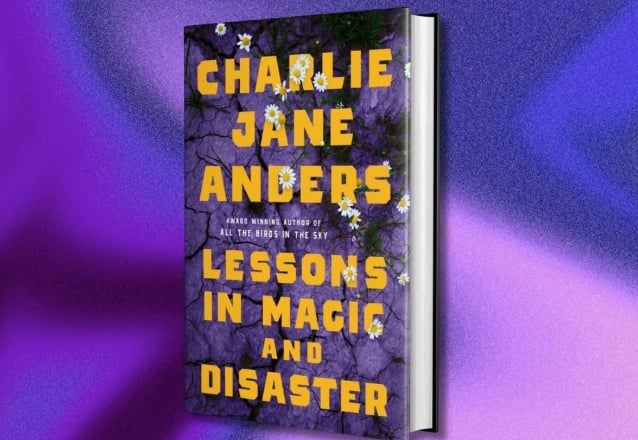

My novel Lessons in Magic and Disaster comes out Aug 19! It’s about a young trans witch who decides to rescue her depressed mother by teaching her how to do magic. It’s my most personal book yet, and I cannot wait to share it with you.

You can pre-order it anywhere, but if you pre-order from Green Apple Books I will sign, personalize and do a doodle. (Please be specific in the comments field about personalization!) Submit your receipt to get some goodies!

Also! I am going on book tour to SF, Portland, Chicago, L.A. and Seattle. Please please RSVP at these links.

I have to tell you, I am freaking out right now. Launching a book in 2025 feels like singing belle-epoque opera in an abbatoir. So I am inexpressibly grateful to everyone who has supported Lessons in Magic and Disaster. <3

This genderqueer performer was a major Georgian scandal

I’ve talked a lot already about the rebellious women and queers of the 18th century, who lived colorful lives and published incredible books during a time of increasing repression and resurgent patriarchy. But I haven’t even told you about Charlotte Charke yet!

I am obsessed with Charlotte Charke — I came across her during my research blitz for Lessons in Magic and Disaster, and I was astonished and kind of pissed that I didn’t already know about her. She ended up playing a pivotal role in the 18th century sections of my novel, and I’d love to make her a major character in another book sometime.

And once I’m finished telling you about Charlotte, you’ll be obsessed too.

(I’m using she/her pronouns for Charlotte Charke, because that’s what she used when she was alive. But it’s pretty clear that she was transmasc.)

Charlotte Charke was the daughter of Colley Cibber, an actor/writer/impressario who became the Poet Laureate of Britain. Colley Cibber was known for playing an over-the-top parody of a peacocking gentleman called Lord Foppington, complete with ginormous wig and Liberace-level clothes. From an early age, Charlotte took after her father: at the age of four, she dressed up in all of his finery, including the oversized wig, and paraded around — taking great care to ensure that everyone saw her.

Soon afterward, Charlotte involved all the neighborhood kids in a weird exploit involving a donkey procession.

This set the pattern for the rest of Charlotte’s life: she was as theatrical as her dad and demanded to be the center of attention. And she was very, extremely masc-identified, dressing in men’s clothing and living and acting as a man as much as possible.

When she was grown up, Charlotte took to the theater, where her brother was also making a name for himself. She soon became known for performing in men’s attire or as a man. As I explained recently, at the time there were breeches roles (where a female character disguises herself as a man for plot reasons) but also travesty roles (where an actress plays a character who is canonically a dude.) Charlotte did both, but increasingly leaned toward the latter — playing roles that had been written for men.

Charlotte married a guy named Richard Charke, who was kind of a scuzzball and eventually fucked off to Jamaica to die young. She got sucked into the politics of the theaters — which were the places where everyone gathered and where political disputes often played out, but also which featured endless controversies over various beloved actors. Charlotte’s sister in law, Susanna Cibber, was at the center of a lot of pamphlet wars and arguments.

A major turning point in Charlotte’s career arrived thanks to Henry Fielding, the satirist who later wrote Joseph Andrews and Tom Jones. Fielding started his own rebel theater company at the Little Theater, Haymarket, and used it to mount attacks on his political enemies. Fielding hated the government of Prime Minister Robert Walpole, and all of Walpole’s supporters — who very much included Charlotte’s father, Colley Cibber. (Remember how Colley became Poet Laureate? That was a political appointment, in return for his vocal support of the Walpole regime.)

Henry Fielding offered Charlotte Charke a lot of money to join his “Great Mogul Company,” and gave her top billing in a ton of plays. And eventually, Henry wrote a play called Pasquin, which made fun of Colley Cibber directly — and he cast Charlotte Charke as an exaggerated parody of her father. Charlotte was absolutely on board, and totally eager to do an even more over-the-top version of her father’s famous Lord Foppington routine.

Colley Cibber pretended to be amused by the whole thing, but was not-so-secretly furious. He cut Charlotte off, and she spent the rest of her life trying to regain her father’s favor (and access to her father’s money.) Charlotte eventually published a memoir that is entirely aimed at creating a reconciliation with her dad — to no avail. Her older sister seems to have despised her and poisoned the well against her, but also she couldn’t keep from being her own outrageous transmasc self.

Those years with the Great Mogul Company at the Little Theater, Haymarket seem to have been the happiest and most prosperous of Charlotte’s life. And then it all came crashing down. In 1737, Parliament passed the Licensing Act, which shut down all theaters that didn’t have a special license – basically putting most actors out of work and ending theater as people had known it. Fielding pivoted to writing novels, which became a much more important art form as theater faded. Charlotte was shut out of the acting profession in London, more or less for the rest of her life.

Charlotte hit on an ingenious solution: she set herself up as a puppeteer, with a super popular Punch-and-Judy show. This worked splendidly, and she was well on her way to securing a comfortable life for herself — until a sudden illness put her out of action and ended her puppet theater career.

After this, Charlotte did whatever she could to survive. She often lived and worked as a man, taking jobs like butcher or manservant that were reserved for men. She started going by the name “Charles Brown,” and at some point she acquired a wife. We know literally nothing about the woman who lived by Charlotte’s side for many years, except that she went by Mrs. Brown. Charlotte would work as a man here and there in London, but these gigs never lasted for one reason or another — some of it was prejudice against her gender presentation, but a lot of it seems to have been due to the fact that Charlotte was terrible at business. She was constantly self-sabotaging.

The other thing Charlotte did to survive was to travel around England as a “strolling player,” usually as part of a theater company that carried all their costumes and props on their backs. She and Mrs. Brown would travel from town to town, doing a repertoire of popular plays and living on whatever money they could make. There’s an amazing story about Charlotte visiting one town where the local heiress saw her and was lovestruck, inviting her to visit. The heiress seemed determined to try and marry this dashing actor, until Charlotte confessed her real identity.

Charlotte had written plays in her youth, and as she got older, she followed Henry Fielding into writing novels. (I haven’t read them; everyone says they’re not terribly good.) She also wrote the aforementioned memoir, which is jaunty and entertaining but also full of self-censorship since her goal was to gain her father’s forgiveness. She was frequently broke and on the edge of debtor’s prison, and she had a super rough life in later years.

At one point, Charlotte returned to the stage in the town of Bristol, promising publicly that she would perform in female clothing and avoid any of her past gender-nonconformity. Some newspapers alleged that she was still dressing as a man, and she was forced to rebuke them in print. She died just a few years after her father.

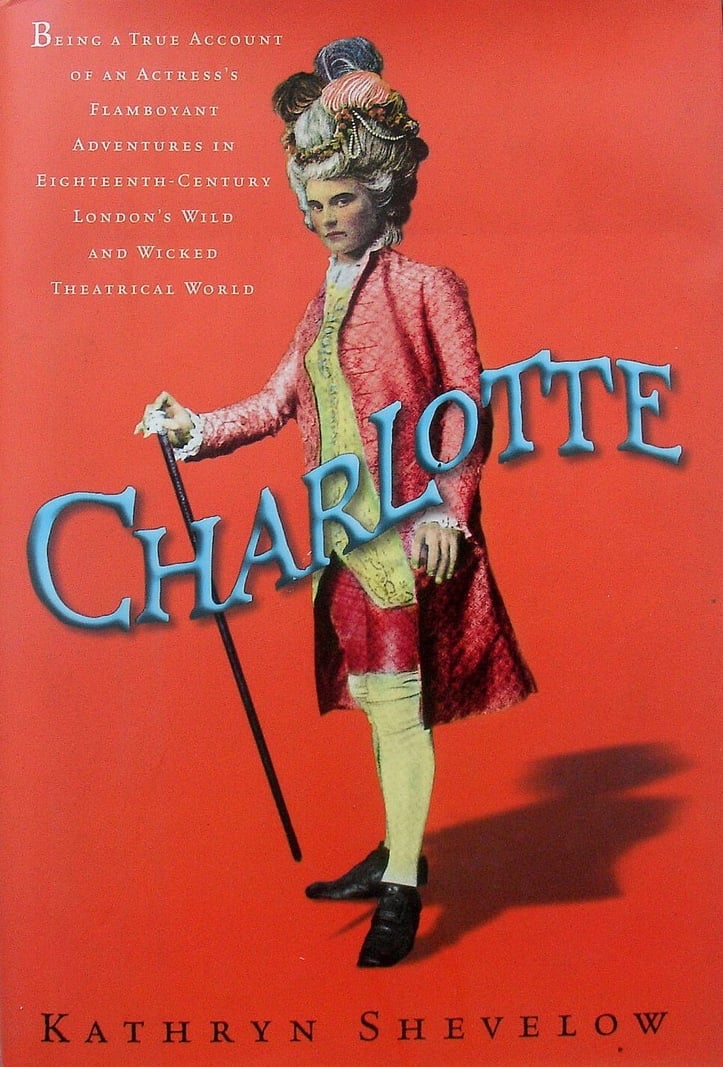

If you want to know more about Charlotte Charke, I highly recommend Kathryn Shevelow’s biography, Charlotte. Charlotte’s memoirs are in the public domain and easy enough to find online.

Music I Love Right Now

I’ve taken far too long to get into Fishbone — their blend of funk, rock and ska kind of grew on me over time. I first heard about them when I was a kid in a church choir (which is where I learned about funk music in general) — one of the older baritones, Theo, was telling his friend that their latest release at the time was funky, but it was “a Fishbone kind of funky.” For years after that I had a sense that there was a asterisk next to the funkiness of Fishbone. More recently, I’ve been listening to their whole back catalog and appreciating the hell out of it.

And now, Fishbone have a new studio album, their first in forever. And Stockholm Syndrome is utterly brilliant and very, extremely timely. Songs like “Racist Piece of Shit,” “Why Do We Keep Dying” and “Last Call in America” hit extremely hard in 2025. I’ve been listening to this album nonstop since it came out a week or two ago, and it’s already one of my favorite releases of the year. There are so many earworms, but also songs that keep growing on me and gaining new depths the more I listen to them. The actual music is upbeat but furious, from the discofied horns of “America” to the jazzy stylings of “Gelato the Clown.” And yes, it is a Fishbone kind of funky — which I’ve come to realize is a kind of funky that very much works for me. Do yourself a favor and pick up Stockholm Syndrome ASAP.