The Teacher Who Saved My Life (and Made Me a Writer)

Over at Tor.com, I’ve been writing essays about how to use creative writing to get through tough times, and I’ve included some stuff about my writing career. But the very first time that creative writing helped me to survive, I was just six years old.

I had a severe learning disability in elementary school—I nearly flunked out of first grade, second grade and third grade. I couldn't hold a pencil right, no matter how many times people showed me, and when I tried to put words on paper, it was just an unreadable jumble. I sat and stared at my blank notebook page, inhaling the scent of stale PB&J crumbs and spilt chocolate milk, while the teacher got more frustrated. The other kids identified me as the class idiot, and picked on me worse than ever.

Then a brand new special education teacher took me under her wing. Lynn Pennington saved my life, and started me on the path that led to becoming a writer.

Ms. Pennington spent hours and hours with me, trying to help me get around my mental block that made me struggle with not just penmanship, but being able to form words at all. I remember it as being almost like a blight slowly lifted.

I'm still friends with Ms. Pennington today—I will always call her Ms. Pennington—and she recently sent me some photos of me as a first-grader, looking dolefully at a page. She's filled in some of the gaps in my memory, and I've realized there was more to the story than I realized at the time.

Like, I hadn't realized just how nuts I drove my teachers, and how much they complained about me in the teacher's lounge. I could read ahead of my grade level, but Ms. Pennington spent ages just teaching me to hold a pencil the right way, and to recognize the difference between letters and the squiggles I was creating. A lot of people would have just run drills—making me write a hundred letter A's, until I got it right—but Ms. Pennington tried to get me to do one decent A, and then help me recognize why it was correct. She was working on "perceptual formation," as she puts it now.

I was this heedless daydreamer, a mumbling oddity who slouched around the schoolyard making up stories in my head instead of talking to other kids. I had imaginary friends, and imaginary adventures, and a whole imaginary life. And Ms. Pennington turned my tendency to daydream into a tool for getting me to learn. And in the process, she made me into a lifelong storytelling addict.

Ms. Pennington gave me lots of gold stars and praise, when I got a letter right, but she also offered me a much bigger bribe. If I mastered all my writing skills and got up to speed on my classwork, then I could write a play—and we'd get it performed at school. Eventually, toward the end of first grade, I wrote this play called The Bad Cad, and to hear Ms. Pennington tell it now, you could see my writing getting smoother and more legible the more I worked on it.

The story of this play was basically what it sounds like: The Bad Cad is a trouble-maker, who goes around wreaking havoc and screwing with an uptight authority figure (who was my older brother, in the play's one and only public performance.) She recently sent me some photos of the one and only performance of The Bad Cad—see above—and you can see my face lighting up on stage. This was probably my first ever work of creative writing.

My mom recently told me that she was in a group of parents back then, and she heard one of the moms brag to the others that her child was in Ms. Pennington's Special Needs class. Because, my mom says, the word had gotten around that there was this one teacher giving all this extra one-on-one attention to the learning-disabled kids. And this had become a status symbol among the trendy parents at Southeast Elementary School.

Here I am with Ms. Pennington, after the performance of The Bad Cad:

Ms. Pennington made me feel safe at school, and less like a Problem Child. I would sit in her lap and hug her, and I drew her pictures of Bert and Ernie from Sesame St., with messages like, “I like having you as a teacher.” She was the first authority figure who didn’t try to punish me for having trouble. Because even after The Bad Cad, I kept driving all my other teachers nuts.

I was so uncoordinated, it went beyond regular clumsiness. Ms. Pennington says she actually took me to the local Children's Hospital, with my parents' permission, and had me tested. I was diagnosed with Sensory Deprivation Integration Disorder. "I remember teaching you how to throw a Frisbee very systematically, and showing you how to stand and how to hold your arms," she told me recently.

Around this time, my parents started taking me on weekends to a physical education program for special-needs kids. I remember learning to swim alongside kids with Down Syndrome and other disabilities, and getting drilled on basic coordination stuff, in a big rec center on the nearby college campus.

In second grade, Ms. Pennington came up with another project for me. I would create a fake newspaper, which mostly consisted of silly political cartoons—I may or may not still have a photocopy someplace of my fake broadsheet, with a ridiculous political cartoon showing the President's "Cabinet" (full of outlandish kitchenwares).

And as a reward, she took me out of school for a day, and we went to Hartford, a 45-minute drive away, and we toured the headquarters of The Hartford Courant, just the two of us. I remember seeing the sprawling offices, but also the big printing press, with the comically huge rolls of paper. (In the late 90s, I went to work for a newspaper, and found that it had an identical printing press, with identical paper rolls, in its basement.)

I never got particularly good at school, not until sometime in middle school. Once I could actually write, I spent my time scribbling Doctor Who fanfic in all of my school workbooks—this is one of the things I remember from back then, and apparently it made an impression on other people. "You were off in your Doctor Who world, when you should have been doing some work," was one of the first things Ms. Pennington told me, when I called her up to ask her some questions for this piece.

In third grade, I hit another snag: I couldn't do math. At all. Basic addition and subtraction, even when I seriously concentrated, I was hopeless at. When Ms. Pennington started to work with me on math, she realized that math problems were taking me forever, because I was making them more complicated than they needed to be. Like, if I had to figure out seven plus nine, I figured out seven plus three plus three plus three.

So Ms. Pennington brought in an Education professor from the University of Connecticut, who specialized in math, and he basically found that I had, as she puts it, a "broken pattern" of doing math. She had to teach me addition and subtraction using "manipulas," or items that you can control with your hands. I got better at understanding higher math concepts, but I was never great at addition and subtraction.

This led to the biggest fight Ms. Pennington remembers having about me. When I started fourth grade, she wanted me to have a calculator, and my fourth-grade teacher absolutely would not allow this. Kids in math class were not supposed to have calculators, or it would defeat the whole purpose. They went back and forth, and Ms. Pennington finally told my fourth grade teacher: Don't try to fight me on this, because you are not going to win this one.

"I probably made that teacher angrier than any of the other teachers were at me," Ms. Pennington told me recently.

I never for a second believed, as a child, that my disability made me any less the hero in my own story, and I give all the credit to Ms. Pennington for that. This was a formative experience for me, and I can't even imagine what sort of person I would be today if I hadn't come away from that time in my life with the lesson that the answer to severe impediments was to make up the silliest ideas I could come up with, and ride them all the way home.

This piece previously appeared, in very different form, in Buzzfeed.

Something I almost tweeted:

Now that we know that pronouns are rohypnol, I can’t help wondering what other parts of speech are also drugs.

Certainly, prepositions are MDMA. Right? They’re always trying to convince you that you can be near, around, with, and next to everything and everyone. They’re Molly!

Also, gerunds? Gerunds are certainly some kind of amphetamine. They are both nouns and verbs, and that is just some tweaker shit.

What else? What other parts of speech are drugs? Mama needs her syntactic medicine.

My stuff:

Tonight at 6 PM PT, I’m going to be in conversation with Rebecca Roanhorse, author of the amazing new novel Black Sun, at Booksmith. This book is a thrilling and amazing adventure, set in a fantasy world based on the culture of the pre-Columbian Americas, with four vivid and fascinating POV characters.

Tomorrow night, I’ll be talking about my story “The Bookstore at the End of America” for Short Story Club. It’s a fundraiser for the amazing Dog Eared Books in the Castro.

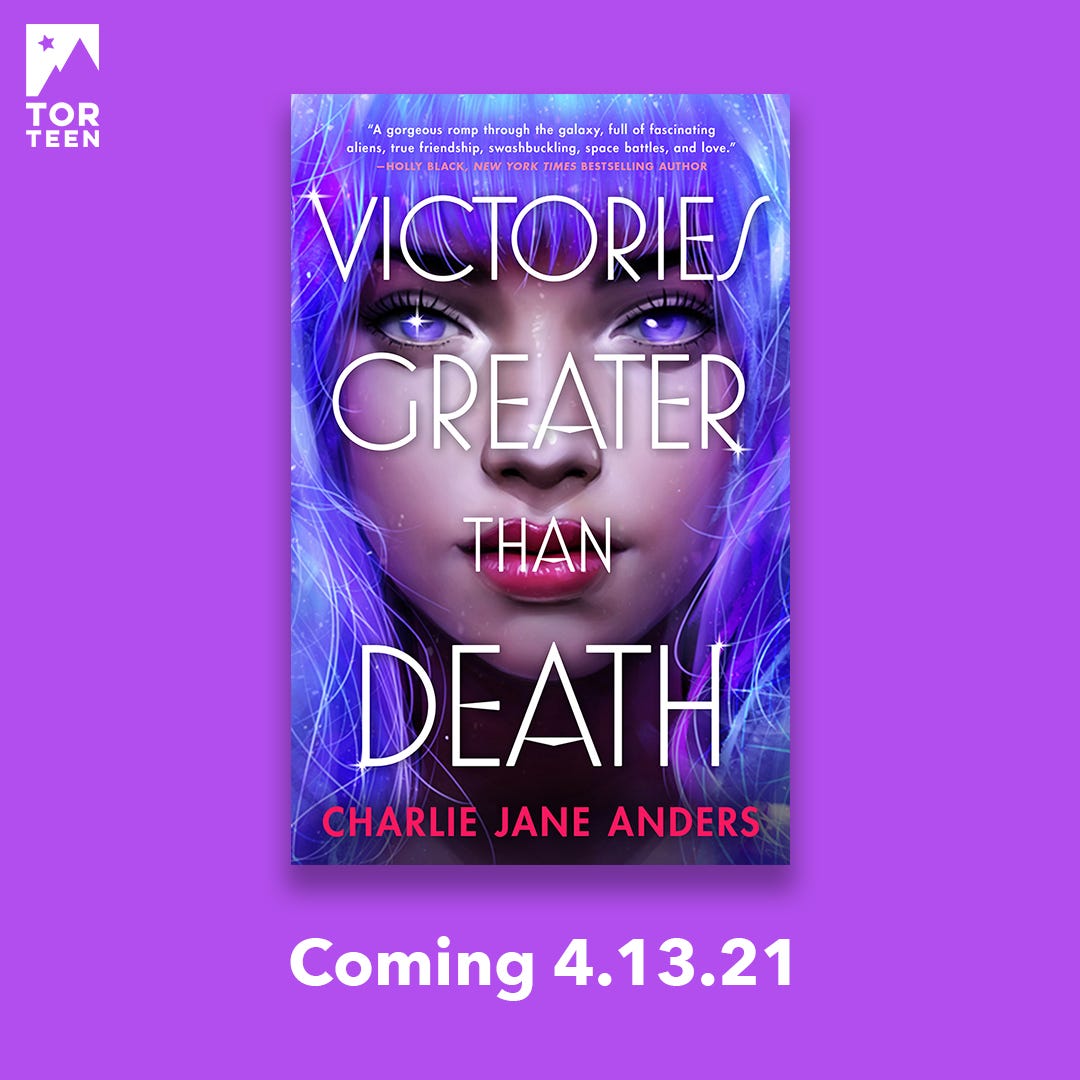

And just a reminder… I would consider it a personal favor if you pre-ordered my upcoming YA debut, Victories Greater than Death. It’s the silliest, funnest book I’ve ever written, and one of my beta readers described it as one big warm hug. This book makes a great gift for the teens in your life, but I also believe it’s good for all ages, just like Star Wars or Steven Universe. And if you wanna read it early, it’s on NetGalley!