The Real Reason Why We Want To Punish the Unhoused

As 2023 ends, more and more people are being left with no place to go. Wars, atrocities and natural disasters are creating incomprehensibly vast numbers of refugees, and I'm afraid this is only a taste of what's coming as both climate change and authoritarianism worsen. And here in the United States, increasing numbers of people are being put on the street — at precisely the moment when Americans are more determined than ever to punish the poor.

We're facing a crisis, and we will absolutely be judged by whether we greet it with compassion or harshness.

In case you missed it, the Department of Housing and Urban Development just reported that homelessness in the United States jumped a startling 12% from 2022 to 2023 as covid-era social programs came to an end.

Two other news stories in the past week have filled me with revulsion. In Missouri, conservative legislators sneaked through a law that criminalized sleeping outside on "state-owned lands" and also limited the use of public funds to build "permanent supportive housing." In other words, in a war on "housing first" policies, Missouri has made it near-impossible for homeless people to get any peace or find permanent housing. Instead, people are forced into temporary shelters, where they must pass drug screening and other checks — after which the shelters will eventually dump them back on the street again. They want to treat the symptoms (drug abuse, other behavioral issues) but never treat the cause.

Meanwhile, in New York City, the beloved Bluestocking Cooperative, one of the best bookstores in the world, is being threatened with eviction because it provided food and Narcan to unhoused people, and allowed them to sit in the store without buying anything. I love Bluestockings so much -- it's where Annalee and I had a book event for our anthology She's Such a Geek, back in 2006. All of the best bookstores are also community spaces, and I'm furious with anyone who doesn't think "community" includes the most vulnerable people.

My hometown of San Francisco is often demonized for its homeless problem by wealthy entrepreneurs and conservative trolls. But the fact is, much as I love my city, we've always exercised maximum cruelty toward anyone with no place to live. In fact, when I first thought about moving here, I hesitated because I didn't want to live in a city with such a cold heart towards its poorest citizens. Twenty-five years ago, San Francisco was already mounting brutal crackdowns against unhoused people, and was viewed as much harsher than Seattle or Portland. It's only gotten worse since then: California's current governor, Gavin Newsom, ran for mayor on a platform he called "Care Not Cash," which involved giving people vouchers instead of cash assistance, cracking down on panhandling, and pushing a lot of people who weren't eligible for the vouchers out of the shelter system. With Newsom's urging, San Francisco also passed a harsh law against sitting on the sidewalk. More recently, San Francisco has been pursuing an aggressive policy of clearing homeless encampments, taking people's property with no recourse. And our mayor has been blocking new affordable housing that's fully paid for.

It would be cheaper and more efficient simply to build enough housing for everyone, rather than pay the high external costs of homelessness. A recent study found that giving people just $750 a month improved their lives measurably, showing that "cash not care" works. But that wouldn't be "tough" enough.

I've written about this before, but when I was younger I was heavily involved in homeless activism and services for the unhoused. I saw firsthand there was no substitute for providing stable permanent accommodation to people in a crisis, and that it's absolutely not true that you must address every other problem before housing someone.

Not having a reliable home means not being able to hold on to your belongings. It means having no stability from day to day, and makes it harder to apply for jobs and other things.

One of the things I'm proudest of from back then is that we worked with the local City Council to set up a program to help homeless people get their first month's rent and deposit, so they only needed to pay monthly rent on an apartment, instead of having to pay a giant lump sum up front.

I'm very familiar with the desire to judge unhoused people for their choices, or to insist that they need to fix themselves somehow before they can "deserve" housing. When I used to volunteer, I got into endless arguments with my fellow volunteers who expressed outrage that our clients were not "grateful" enough for our largesse, or who insisted they only wanted to help the most "deserving" people. As if providing services to everyone, regardless of whether we liked the cut of their jib, was somehow a foolish soft-heartedness.

This idea that some people deserve food and shelter more than others, or that we should judge people's behavior, is hard to shake. It's one reason why I ended up believing that private charity cannot solve systemic problems. A government program usually can't pick and choose its recipients — everyone who meets the criteria gets help. (Red states have been making some efforts to change this, by imposing more and more restrictions on welfare benefits.) Private benefactors, on the other hand, can pick and choose whom they help, based on their own biases. We're better off with programs that help everybody who needs them.

A few years after my stint in homeless activism, I moved to a new place and tried to volunteer at a local shelter. But at my orientation, I was told that I would be expected to judge whether the residents were making enough "progress" in addressing their problems — which might be drugs, alcohol, or simply bad habits that might keep them from being good, upstanding citizens. I was honestly gobsmacked at the idea that I was supposed to snoop on the very people I was trying to help. And I didn't understand why the shelter management would trust me, a random stranger who had wandered in off the street with no real qualifications, to judge anyone. Worse yet, I was told that the residents whom I judged weren't trying hard enough to change their behavior would be kicked out of the shelter early.

Reader, I did not volunteer at that shelter.

"There but for the grace of God go I." That's what every sane person thinks when they see someone who has noplace to live — with or without the "God" part, depending on your beliefs. It's a damn scary thought.

I don't like to believe that a run of bad luck could land me out on the street, even though I absolutely know it's true. I would prefer to believe that there's some essential difference between me and the unhoused. That I am better than them in some ineffable way. That I am protected from their misfortune by my intrinsic virtue. It's not true, but it sure would be comforting to think so.

So I don't think it's just cruelty that makes us want to judge and punish people who are living in precarity. We want to believe there's something wrong with them, because otherwise we have to confront how easily we could end up where they are.

You also can't ignore the fact that unhoused people, by virtue of their extreme visibility and the unsanitary circumstances we've forced them into by taking away so many of their services, are a convenient scapegoat for anyone who is angry or wants someone to blame for the problems of cities.

The latest episode of the podcast Tech Won't Save Us features a fascinating interview with Astra Taylor about her new book The Age of Insecurity: Coming Together as Things Fall Apart. (I haven't read the book yet, but now I'm dying to.) Taylor argues convincingly that capitalism, going back hundreds of years, requires maximum harshness towards poor people, so as to keep the rest of us in a state of anxiety and desperation. We will work as hard as we can for the bosses, as long as we see that the alternative is a kind of living hell. (That interview is absolutely worth listening to in its entirety.)

As part of my research for my upcoming adult fantasy novel, I've been reading a lot about the bizarre marriage of Calvinism and capitalism that was baked into the foundations of the United States. (I guess a lot of this notion comes originally from sociologist Max Weber.) Protestant settlers believed in personal salvation through hard work -- and a lot of the early colonies in North America and Virginia were for-profit enterprises with shareholders back in England. Both the church and the investors were telling people that the sweat of their brow would lead to advancement and save their souls. Hence: Puritan Work Ethic.

So perhaps that's the real problem: we're so brainwashed by the idea of salvation through personal industriousness that when we look at the biggest losers in the game of capitalism, we see not just victims of misfortune but the damned.

Anyway, to reiterate what I said at the start: we deserve to be judged by how we treat our neighbors who lack secure housing. And right now, that judgment will not be kind.

Stuff That I Love

I recently saw two new(ish) movies that I enjoyed a lot.

Godzilla Minus One is an utterly breathtaking kaiju movie with human characters who are both legible and compelling. Oftentimes, the humans in a kaiju movie are just there to fill time until the next monster attack, but I would have watched a movie about these people even if Godzilla never showed up. This film is a brilliant anti-war parable, that gets brutally deep into the callous way that governments throw away human lives. I keep thinking about it, and I hope it's not too late for you to see it on a big screen.

American Fiction, written and directed by my former coworker Cord Jefferson, is an incredible satire about a Black literary novelist who decides, as a joke, to give the publishing industry what it wants from Black authors. This film isn't afraid to skewer the hypocrisy and cluelessness of white people in the book world, but it also resists oversimplification. Issa Rae, playing another Black author, adds a lot of complexity and nuance to the story — and meanwhile, Jefferson weaves in a grounded family story about dealing with a parent's dementia. Based on a novel by Percival Everett, American Fiction manages to encompass a range of tones without falling apart, thanks in large part to Jeffrey Wright's tour-de-force performance. Definitely see this one in a theater if you can.

My Stuff

This Saturday, Dec. 30, my novel All the Birds in the Sky will be just $2.99 in all the ebook formats for one day.

The latest episode of the Our Opinions Are Correct podcast is about Doctor Who, and why it's still one of the best shows on TV after sixty years.

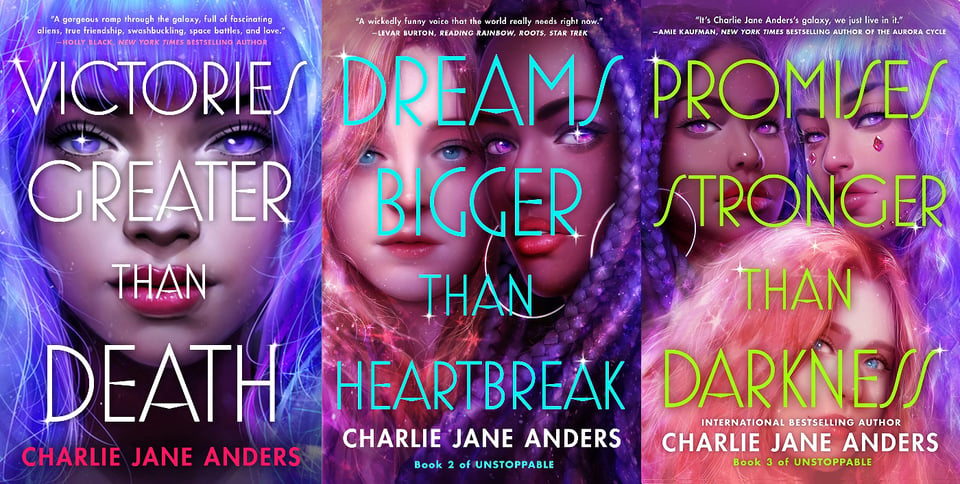

I wrote a YA space opera trilogy about queer kids who save the galaxy! The first two books, Victories Greater Than Death and Dreams Bigger Than Heartbreak, both won Locus Awards and were nominated for the Andre Norton and Lodestar awards respectively. The third book, Promises Stronger Than Darkness, came out in April, and the paperback comes out in a few months.

Also, I co-created a trans superhero for Marvel named Escapade! She's introduced in the 2022 pride issue, and she has further adventures in New Mutants Vol. 4 followed by New Mutants: Lethal Legion (preorder link.) I'm still really proud of the nine-part story we managed to tell about her, but either of those trade paperbacks should also stand on its own.