The Most Surprising Book Trend Right Now: Memory-Sharing

If you asked someone to name the main trends in genre book publishing from the past year or two, they'd probably mention romantasy, cozy fiction, horror and a few other things. But I've been blown away by a sleeper trend lately: novels about people storing their memories remotely, gaining access to someone else's memories, or sharing a memory with another person. In general, memory seems to be on a lot of people's minds lately.

Just recently, I've loved a ton of books on this theme. The notion of copying, storing and sharing memories isn't exactly new -- in fact, I played with it quite a bit in my novel The City in the Middle of the Night. (Yoko Ogawa's influential The Memory Police also deals with the ways our memories are controlled and overseen.) But this new wave of novels is using the concept to explore deep questions about personal identity, as well as the ways that our memories can be politicized and policed by repressive regimes.

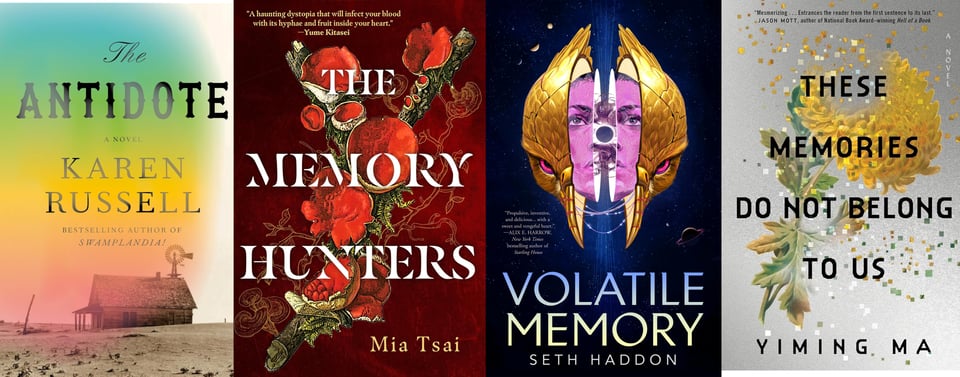

To find out more about this topic, I talked to four authors of recent books that deal with this concept in various fascinating ways. (I also reviewed some books on this theme a while back for the Washington Post.)

One of my favorite books of 2025 was The Antidote, the long-awaited new novel by Karen Russell. The Antidote is the sobriquet of a prairie witch in dustbowl-era Nebraska, who acts as a sort of bank vault for people to store their unpleasant memories — with the promise that you can retrieve the memory later when you need it. But after a catastrophic dust storm, the Antidote and other prairie witches find their vaults cleaned out, all the stored memories gone forever.

The Antidote turns into an examination of buried historical trauma, especially the attempted genocide of Native Americans — thanks in part to a New Deal photographer's magical camera that takes pictures of the past and future.

In writing The Antidote, Russell says, "I was interested in what happens when people are unable or unwilling to reckon with the past, in the exiling of memories from our waking consciousness and from our public histories, those things that many of us must continuously forget or suppress in order to go on living as we do, and how that 'collapse of memory' harms us individually and collectively."

Russell adds, "I do think that whatever else a memory might be, it's never the fullness of what happened. It's always a (re)creation, never static or inert." And that "these secrets that can feel so private and so personal, can become, in aggregate, something like a mass denial. Who and what we exclude from our family stories and collective histories has tremendous consequences, for all of us."

Russell says that while she was researching the novel that became The Antidote, she learned about an astonishing act of curatorial violence. Everyone has seen the iconic Dust Bowl photographs taken by New Deal photographers like Dorothea Lange — but the architect of this program, Roy Stryker, used a hole-punch to destroy the photographic negatives he didn't want to include, in what Russell calls "an act of artistic curation and in some cases political calculation." Russell says there's a "shadow archive of unpublished and hole-punched negatives," suppressed for decades, which you can now view online at the Library of Congress.

Russell kept returning to one particular image of "a student with a hole-punched ear," and "that hole-punched negative came to feel like the heart of this novel."

Another book I loved in 2025, Mia Tsai's The Memory Hunters, takes place in a world where some special people, like Key, can harvest memories from other people. Key can also unearth memories from people who lived long ago, using a complex process involving mushrooms. When Key finds an old forbidden memory that contradicts the official record and threatens the political order, she's forced to hide it -- but the memory is taking over her personality and she's in danger of losing herself. Her bodyguard and lover, Vale, is forced to take drastic measures to save her.

Tsai says she's always been fascinated by the concept of memory. "Memory is magic!" she says. "How can something so crucial and something we stake our lives and personalities on be so easily tampered with?" Tsai points out that a lot of books that came out in the past year were probably acquired in 2023, and written in 2020-2022, if not earlier. And there's one thing about the early 2020s that seems especially relevant to her.

Says Tsai:

I think the wave of memory-related books has a lot to do with how we've been gaslit as a nation over how devastating Covid has been and continues to be (plus the global gaslighting over the genocides to which we're daily witnesses). What we experienced and what we remember does not match up with what we're being told. And invalidating a memory is so deeply personal. It's hurtful and provocative to say, 'No, that's not how it went.'

The gaslighting began before Covid, of course, and the first Trump administration was already bombarding us with lies and trying to erase the very existence (and accomplishments) of marginalized communities. All this, while "burying our ability to process beneath continual outrage," says Tsai. "In a way, sharing memories to verify their realness became a way to bond with someone else, a way to confirm that what we experienced was real, unbelievable as it was."

Tsai sums it up perfectly: "Memory-recording lets us know we were there and it happened; memory-sharing proves we were alive and not alone."

Recently, Tsai visited some Civil War battlegrounds, and saw a monument to Confederate general Stonewall Jackson. Nearby, there was a sign entitled, "The War Over Memory," which detailed "one of America's first great delusions," or one of our earliest propaganda campaigns, "the effects of which we're still feeling 160 years later."

It's not just that we're being lied to about events that we personally witnessed, says author Seth Haddon — it's that we have more ability to witness those events than at any other time in history, because we're all connected. We can share the experiences of people around the world who are "enduring violence, displacement, [and] oppression." And at the same time, mainstream and official narratives present a very different picture of reality. "This gap between lived (or viewed?) experience and official stories has made the question of memory feel newly urgent," says Haddon.

In Haddon's great space-opera novella Volatile Memory, a trans scavenger named Wylla finds a mask that gives her enhanced abilities — but when she wears the mask, she also experiences the memories and consciousness of the dead person who wore it before, a woman named Sable. Haddon uses the sharing of Sable's memories to ask some deep questions about how our memories make us who we are, but also how our embodiment shapes our experience of being alive.

Haddon says that the notion of "preserving the self" is even more important when we're under so much pressure to deny what we're witnessing. The main way we can preserve the self is by holding on to memory, "even if it can't be free from personal/contextual bias." Our memories end up "feeling more intimate and trustworthy than the flood of information we receive from elsewhere, especially in a time when so many sources feel compromised." We feel as though an individual person's memories are "purer and more authentic" than the narrative shared by a lot of people, even if the notion of authenticity is inherently messy.

Yiming Ma's fascinating These Memories Do Not Belong To Us takes the theme of censorship and repression to a further extent, taking place in a future dominated by a new Qin Empire, in which everybody has a Mindbank that records their memories. Some past memories are contraband, either because they have subversive themes that the government disapproves of or because they contain historical events that the government wants to cover up. Ma's novel in stories contains a narrative assortment of forbidden memories, which the main character has inherited after the death of his mother.

Ma says that he was interested in resilience when he wrote These Memories, because it's by having a shared narrative that we can "stay resilient and resist" during times of political turbulence. This shared narrative can come from writing that explores "both individual and collective memory."

Ma also was inspired by the fact that researchers have continued to make a lot of new discoveries about how memories are made and stored. For example, scientists have new evidence that memories can be stored outside the brain, and that our memories are dynamic rather than static, meaning that we are constantly revising them every time we revisit them. And that long-term memories can form independently from short-term memories.

Ma was also inspired by research that reveals that some people cannot form mental images, which shows "how differently we all experience our memories and dreams."

I was also struck by a moment in the recent novel Slow Gods by Claire North. An artificial intelligence explains that artificial minds store memories the same way humans do: by compressing them into narratives with most of the details stripped out, because the raw sensory data is too huge to store in the long term. I also found it fitting that the last book I read in 2025 was There Is No Antimemetics Division by qntm, in which monsters go around devouring people's memories, and one particularly terrifying monster kills anyone who can remember that it exists.

What I've personally gotten from this recent flood of books (and what I tried to explore in The City in the Middle of the Night) is that even though we fixate on individuality — the notion that one person's experience is totally unique — the more we can share our experiences, the more we can realize that we are one. That our fates, and our pasts, are bound together, and memory is always, on some level, collective as well as personal.

I also increasingly think that being able to experience another person's memories is a higher form of empathy -- and empathy is something we are all longing for right now, in the midst of so much performative cruelty. Not to mention community, which can only be formed by the feeling of shared heritage. (And heritage is in many ways just another word for memory.)

Says Tsai, "I don't feel this every day, but I certainly do now: What a glory it is to continue surviving and making memories with others."