The Incredibly Risky Scheme that Bill Gates Keeps Pushing

Climate change keeps getting worse: 2023 was the hottest year on record, and it's not even close. Despite increasing investments in clean energy and other reasons for optimism, we're still pumping more and more carbon into the atmosphere. And meanwhile, OpenAI's Sam Altman, at the Davos forum in January, confessed that the energy needs of the semiconductors that power OpenAI's apps have turned out to require much more energy than people had expected, which means we're going to have to burn a fucktonne more carbon in our ongoing quest to create real A.I. (as opposed to the fake kind we have now.)

Altman believes we'll eventually develop nuclear fusion that can provide clean power to his data centers — but in the meantime, what do we do about all the carbon he's burning in the never-ending quest to fellate Roko's Basilisk? Altman told Bloomberg news that we'd have to "do something dramatic" and use "geoengineering as a stopgap." (via DisconnectBlog.) Altman is joining other tech leaders, chiefly Bill Gates, in proposing that we fix the problems caused by our fucking with our atmosphere by... fucking with our atmosphere.

This scares the shit out of me.

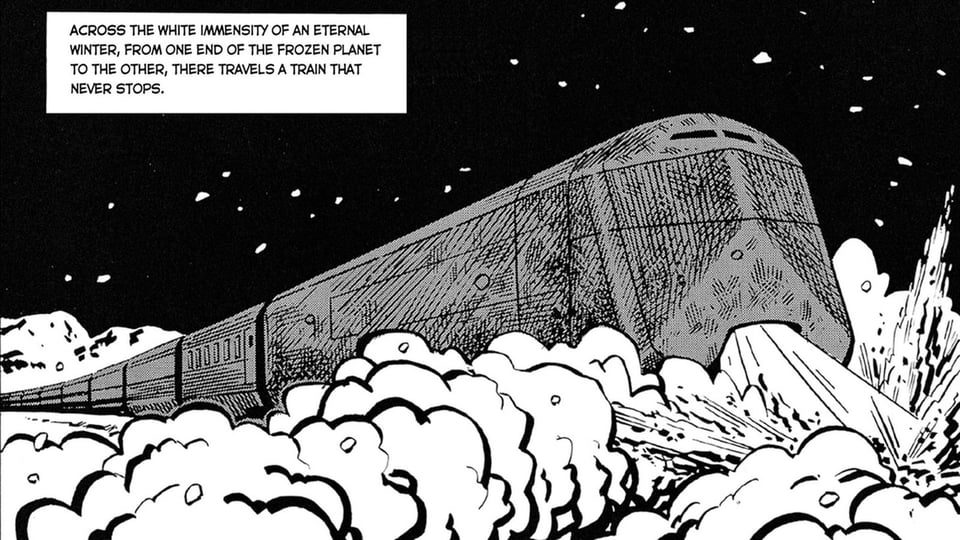

Geoengineering is incredibly risky, and even some of its proponents warn that it could wind up doing more harm than good. If you're a science fiction creator reading this, and you're looking for an apocalyptic scenario that doesn't involve nukes, zombies or meteor strikes, you could do a lot worse than writing about a geoengineering disaster. (This was one reason I was excited to be on the writing staff of the Snowpiercer TV show for a hot (cold) minute: Snowpiercer is probably the most famous story about geoengineering gone wrong.)

What is geo-engineering?

Basically, it's a way of mitigating the worst effects of climate change by putting stuff into the atmosphere that reflects sunlight away from the Earth, thus cooling the planet down somewhat. The most commonly discussed form of solar geoenginering is called Stratospheric Aerosol Injection, or SAI, in which an airplane flying at high altitude sprays special reflective aerosols into the atmosphere. Huge volcanic eruptions have cooled the planet in the past, so you can see why simulating a covering of volcanic ash might seem like a good idea.

There are other theories of geoengineering, including marine cloud brightening — spraying particles into clouds over the ocean to make them reflect more sunlight upward. And also putting honking big mirrors into space, also to reflect sunlight away from the planet.

When people talk about geoengineering, "overall, most people are talking about [putting] aerosols in the stratosphere," says Holly Jean Buck, Assistant Professor of Environment and Sustainability at the University at Buffalo. Maybe ten to twenty percent of geoengineering conversations also mention marine cloud brightening, and then other approaches are rarely brought up.

What are the risks of geoengineering?

Let's just start with the notion that it's a massively untested intervention into a delicate, complex system that we still don't fully understand. Climate scientists have also brought up a variety of worries about what could happen if we start spraying reflective stuff into our atmosphere.

Alan Robock, Distinguished Professor of Environmental Sciences at Rutgers University, shared with me a web page containing a whopping 74 scientific papers he's written about geoengineering and its risks. Among other things, injecting aerosols into the stratosphere could deplete our planet's ozone layer, increasing people's risk of skin cancer. Also, some regions might suffer much worse droughts and vastly reduced crop yields, which could lead to widespread starvation. In particular, places like India which depend on monsoons might be out of luck. Those stratospheric aerosols could come down to Earth and pose a health risk to people on the ground. Ocean acidification would continue to get worse, and might even be slightly worse than without any geoengineering. One common thread: geoengineering could help some parts of the world, while making things worse for others.

This 2021 paper also provides a great rundown of the concerns that people have raised about geoengineering. One risk that worries me is the risk of overcorrecting: cooling the planet too much and then not being able to course-correct. (This is the scenario that's taken to somewhat outlandish extremes in Snowpiercer.)

Meanwhile, there's also the risk that we could use geoengineering to cool the planet and suddenly stop — creating a sudden blowback. If we started geoengineering and then stopped abruptly, temperatures might increase so rapidly, humans might not be able to survive, a scenario referred to as "termination shock." (Update: I somehow forgot that Neal Stephenson had published a novel about this exact concept, until someone reminded me online.) Even though geoengineering is often pitched as a "stopgap solution" while we figure out other options, one recent paper argues we'd have to keep doing it for at least a century, which would massively increase the risks.

Okay, but how do people respond to all these dire warnings?

In addition to Buck and Robock, I also spoke to Ken Caldeira, senior scientist (emeritus) at the Carnegie Institute of Science and an adviser to Bill Gates. Caldeira told me that "some of [Robock's] concerns are legitimate," but that Robock has failed to update his views as the science has developed.

In particular, Caldeira pointed me to this 2019 paper by Peter Irvine et al., in which they model the impact of using geoengineering to reduce atmospheric carbon by 50 percent. And they find that the thing I mentioned earlier, where some regions get better while other regions get worse, is not such a great problem with "moderate" geoengineering. And this 2023 paper by Jonathan M. Moch et al., which among other things says that an increased risk of skin cancer from ozone depletion would be offset by reduced mortality from air pollution. (The Moch paper also says that SAI would be more effective than expected in some regions and less in others, and it cautions that we can't fully know how pumping sulfites into the atmosphere would affect our atmospheric chemistry.)

So Caldeira is much more optimistic about the net benefits of solar geoengineering than Robock — and yet, he still raises a huge concern.

"My primary concern is that it would work too well," Caldeira says. And this could reduce the pressure that policymakers currently feel to phase out fossil fuels and stop using "the atmosphere as a waste dump."

Adds Caldeira: "The end game of ramping up greenhouse gas concentrations and solar geoengineering deployments is not very attractive." He worries that if we rely on geoengineering without reducing our carbon, we'll run into trouble — because we'll need to pump more and more particles into the atmosphere, and geoengineering will work less well as we scale up. This is in line with the Irvine paper, which shows benefits for modest geoengineering, but not so much for massive scales.

Basically, the best case scenario is that geoengineering might buy us a bit more time to transition to clean energy — but policymakers could easily be tempted to use it as an excuse to keep delaying forever.

How to talk to people about geoengineering

Policymakers have definitely not gotten on board with the idea of geoengineering yet — lawmakers in the state of Tennessee just passed a law banning it, in fact. (In part because they seemed to confuse geoengineering with chemtrails, a common conspiracy theory.)

Buck wrote a book about how to imagine different post-geoengineering scenarios, called After Geoengineering. And in her research, she does interviews, focus groups and surveys to see how the public feels about the concept of geoengineering. In general, people are skeptical, saying things like, "That's not going to work. That's super risky. I've never met anybody that's like, 'Oh, great. This is going to deal with it.'" She says some people bring up Australia's history of importing cane toads to deal with beetles, only to be overrun by toxic toads. This plague of toads provides a powerful metaphor for the dangers of believing we know enough to mess with the environment to achieve a particular goal.

Buck cautions that people's attitudes to geoengineering could change as the climate worsens. But right now, she's not too worried about public support for this option. "I'm more worried about particular elite decision-makers."

Sometimes Buck shows people this five-minute video from CBS News, which includes Bill Gates advocating geoengineering:

"Once you mention Bill Gates is looking at this," ordinary people immediately oppose the idea, says Buck. "Man, they really hate him."

What worries Buck is that research on geoengineering will be funded by private industry, which wants to find an excuse to keep building endless data centers and burning endless carbon. (This recent New York Times op-ed expresses similar concerns.) Buck supports a 2021 plan by the National Academies to carry out a publicly-funded, peer-reviewed research program that makes its data available to everyone. The National Academies plan, she says, includes "staged off-ramps if it's found that the bads are really bad." In other words, we need a safe way to stop the research, if the risks turn out to be too great.

"Those Silicon Valley guys aren't going to embed that kind of thinking in their own research and the stuff they fund," warns Buck.

Something I Love Right Now

The Second Best Hospital in the Galaxy is an utterly delightful new animated show (on Prime Video) about a space hospital full of alien patients and doctors. Basically, picture Grey's Anatomy, but featuring time loops and bizarre alien parasites. And sexually-transmitted infections that change your DNA so you look like the last person you had sex with. Second Best Hospital, simply put, is the show that I always wished Rick and Morty would be: gonzo, outrageous, full of over-the-top science fiction ideas, feverishly clever, and side-splitting funny. But I adore its cast of characters, especially the two heroes, Dr. Klak and Dr. Sleech. The voice cast includes Kieran Culkin, Stephanie Hsu, Natasha Lyonne, Maya Rudolph and Bowen Yang. I haven't heard much about this show, which saddens me because it ROCKS.

My Stuff

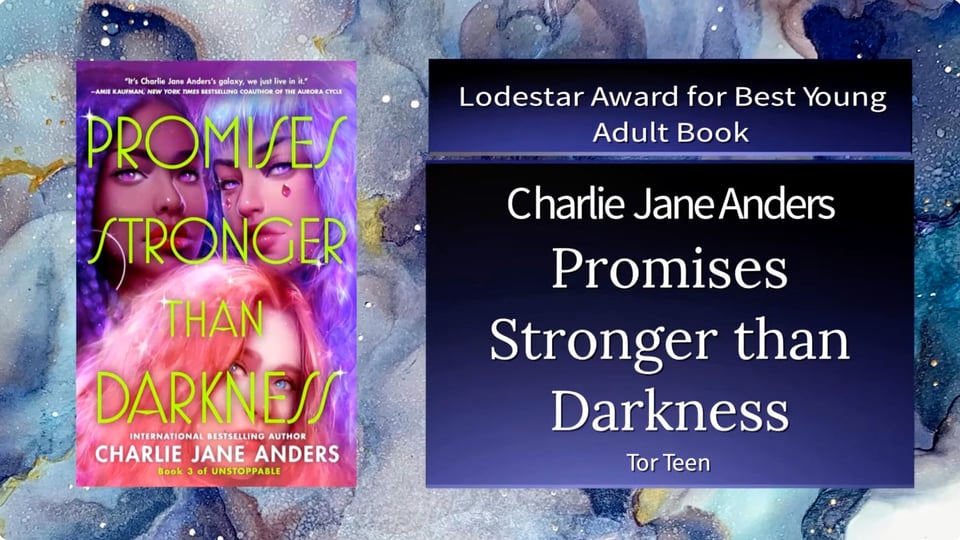

Amazing news: my YA threequel Promises Stronger Than Darkness was just nominated for the Lodestar Award for Young Adult Fiction, which is given out at the Hugo Awards but is technically not a Hugo. This means that all three books in the Unstoppable trilogy have been Lodestar nominees. Also! Promises comes out in paperback on April 9, and you can pre-order a signed, personalized, doodlefied copy from the wonderful Green Apple Books. (Please put personalization requests in the "order comment" field.)

The Trans Nerd Meetup is back! It's this Saturday from 12:30 until whenever at Zeitgeist in SF. Anyone who self-identifies as trans/nb/gnc and loves to nerd out is welcome.

My next book review should be out in the Washington Post sometime in the next week. And if you're looking for book recs, I have a massive backlog now!

The latest episode of Our Opinions Are Correct features an interview with Dr. Chuck Tingle about queer horror!

You can buy two trade paperback collections featuring Escapade, the trans superhero I co-created: New Mutants Vol. 4 and New Mutants: Lethal Legion. If you want the very first appearance of Escapade, you need to find a copy of the 2022 pride issue, which is on Marvel Unlimited but otherwise (sob) out of print.

I've also written some more books! Never Say You Can't Survive is a guide to writing yourself out of hard times. Even Greater Mistakes is a weird, silly, scary, cute collection of stories.