Telling Stories Is Still Saving My Heart and Mind

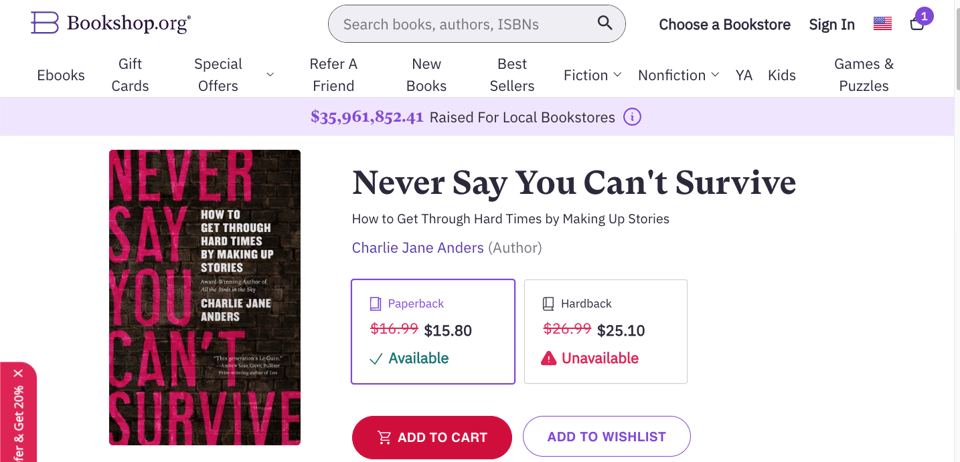

Yesterday, I got an amazing surprise: Green Apple Books asked me to sign a stack of copies of my book Never Say You Can't Survive: How to Get Through Hard Times by Making Up Stories. And they were paperbacks! They looked much easier to carry around in a purse or pocket than the hardcover, and also more affordable. I was so overjoyed.

I had no idea that Tordotcom was putting out a paperback of Never Say You Can't Survive, but I'm so delighted this just happened. Because (to my endless relief) the central message of that book is proving truer than ever, for me at least. I'm finding it nearly impossible to cope with living in the world right now, with all the assaults on human dignity and democracy — except for when I'm working on a fiction project, at which point I can lose myself utterly in my own imagination. It's the one thing holding me together right now.

This timing was especially excellent, because I was already thinking this week's newsletter would be about the fact that writing fiction is the only thing that's keeping me from wanting to scream into a cushion right now. Alas, I have absolutely nothing useful to say right now about fighting against autocracy or fascism, apart from what I've already said. (Start here, here, here, and here.) Other people are saying what needs to be said, way more eloquently than I ever could. I just feel sick inside, and helpless to stop the coup in progress.

The only thing I can really do is try to tell the best stories I can, to give other people hope and courage — and to encourage you to do the same.

The other day, another writer asked me how I can concentrate on writing right now, when the government is being looted and discrimination is becoming official policy. And I guess I have a couple of answers.

First, I think that if you keep writing regularly for long enough, it becomes second nature. It becomes a habit, something you just fall into doing. Sort of like if you practice a musical instrument, or do any other practice that requires skill and concentration, but also passion.

The other answer is that the more time I spend building a character, the more I become fascinated with them and want to spend time with them, and this can be a sort of virtuous cycle. This is something I talk a lot about in Never Say You Can't Survive, and I'm glad it still holds true.

I'm not the person I was when I wrote Never Say You Can't Survive. I still remember when I thought 2020 was going to be a uniquely terrible year, after which things might start to get better. At times, writing that book feels like a strange dream, because I wrote a chapter a week and I was deeply immersed in thinking through my philosophy of writing and self-preservation. So in some ways, the fact that this book still exists and anyone can read it, even though the version of me who wrote is long gone, feels like a real gift.

Anyway, back to the main point: telling stories is still keeping me in one piece, and even bringing joy.

I finished a new novel a couple weeks ago — it's too soon to talk about it, even though I am dying to talk about it. Hopefully it'll be out in 2026 sometime. Even more than this year's Lessons in Magic and Disaster, it's all about trans people and queerness, and how we can take care of each other in the face of a hostile, senseless world. I guess it's a theme.

So now I'm starting a brand new novel — or rather, going back to work on a project that I had put on the back burner ages ago, which now seems like it needs a major rethink. (This always happens when you put something aside and go back to it. All of a sudden, you can see the flaws in everything you came up with before.) Going from finishing a novel to starting a novel always feels like a major comedown, and a total loss of skill points. I've gone from knowing what I'm doing to having no freaking clue. I've already made so many mistakes, and there are characters who I can't quite see clearly yet. It's a struggle, but also a fun challenge.

Outside of writing, everything feels a bit overwhelming. At times, I find myself navigating the world by narrating whatever I'm doing in my head. "Okay, I'm going to the supermarket. Gonna buy some veggies. I need veggies. Gotta stay healthy." Occasionally, this happens out loud, because I'm a total weirdo. (I've been talking myself through story problems out loud for years, so this is just more of the same. Also, my late father used to talk to himself all the time, so I come by it honestly.) When I'm at home alone, I can talk to my cat, who seems to appreciate it.

The point is, narration seems to have a certain power that is hard to access in any other way. The act of narrating means that the world has logic and causality, and the characters in a story (me, in this case) can make choices that have outcomes. Which is very much not how the world feels just at the moment, for anyone who is being targeted for destruction by the new regime.

I'm also gearing up to promote Lessons in Magic and Disaster. Because it's my first novel for adults since 2019, it feels like there's a lot at stake with this one: I have to reintroduce myself to a whole new readership, including a ton of people who may not have been all that interested in my young-adult novels. I feel as though launching this novel is my main job right now, and it's another sort of writing project. In some ways, these days you have to write a novel twice: first you draft the actual manuscript, then you figure out how to tell people the story of how you write the novel, how it took shape, and how it speaks to the state of the world. I'm writing a ton of essays about the book.

I was writing a big chunk of Lessons in Magic and Disaster at the same time as Never Say You Can't Survive, and I talk about Lessons a bit in Never Say. Lessons is also a book about creativity, and using your imagination to deal with scary real-life stuff. Looking back, I can absolutely see how I was using Lessons to process some grief and trauma from the early 2020s, though it's not remotely autobiographical and the characters aren't based on real people. (More on this soon!)

The other day, I came across an interview in the L.A. Times with David Cronenberg, as part of a roundup of four directors who have made films about mortality to deal with death in real life. Cronenberg's wife Carolyn died back in 2017, and he's just released a new film called The Shrouds, about a widower who creates a weird high-tech cemetary where you can watch bodies decompose in real time.

Cronenberg told the Times:

Once you start to write a story, it becomes fiction, and maybe that’s what I needed it to be. I needed to make invented characters. Any artist needs to have distance between what you’re creating and your emotions. They’re there, they’re driving it underneath, but you’re keeping them at a distance.

He added that he hadn't experienced any "closure or catharsis" from making a fictional movie that deals with the real-life passing of his wife, because "I've always felt that art is not therapy."

Anyway, Cronenberg's comments crystalized something I've thought for a long time, which I tried to talk about in Never Say You Can't Survive. Of course, there are many other valid reasons to make art during a shitty time besides directly processing your own pain — but having a place to channel those terrible feelings can be incredibly powerful.

I do write the occasional memoir/personal essay piece, but I've always felt as though I can better deal with my own emotions by removing them from the specifics of real experience. I can put those feelings onto people and situations that I've invented, which puts them at enough of a distance that I can see them more clearly and explore them without getting bogged down. Instead of telling a story about your dog dying, you can write about someone else dealing with the death of their cat. The emotion becomes distilled through the consciousness of a fictional character, and you can explore the particulars of the scenario without getting overwhelmed.

I also don't know if I got any closure or catharsis from putting my actual grief and trauma into Lessons in Magic and Disaster — but I definitely have been able to move forward. My next novel, the one that I hope will come out in 2026, has almost no grief or trauma in it, and is much lighter and fluffier, despite grappling with transphobia and xenophobia. So at least, I felt good enough to change the subject.

And really, that's another benefit of storytelling during a huge collective nightmare: it lets you keep changing the subject, instead of feeling stuck.

Anyway, Never Say You Can't Survive is now a paperback that you can fold up in your back pocket, and I couldn't be happier about it.