Jane Austen Was the First Great Lady Novelist. (Or So I Was Taught.)

Just a heads up: you can pre-order my novel Lessons in Magic and Disaster from Barnes & Noble (online) and get a 25 percent discount — this expires tomorrow. Also, ICYMI I’m doing a pre-order campaign for Lessons. If you share your receipt with me before Aug 19, you can get a PDF of bonus material related to my novel All the Birds in the Sky, including a huge sneak peek of the sequel in progress. (Seeing those receipts come in greatly increases my motivation to keep working on that sequel, so thank you!)

They Tried to Bury These Lady Novelists. We Won’t Let Them.

I've been obsessed with 18th century literature since college. I was an English major for the first two years of my undergraduate degree, and I got seriously sucked into spending a lot of time thinking about Samuel Richardson and Henry Fielding. I ended up reading all of their work, even the more obscure stuff like Sir Charles Grandison and Amelia. I spent endless hours thinking about these two men and their feud.

(More on that in a moment.)

When I started writing my upcoming novel Lessons in Magic and Disaster, I decided to make my protagonist, Jamie, a grad student working on 18th century lit. I figured I already knew a ton about the period. I figured that Jamie would be spending a lot of time thinking about Henry Fielding and Samuel Richardson, and their contrasting approaches to fiction-writing. And I figured that those two men, plus Swift and DeFoe, were the only English novelists of their time who mattered. After all, that's what I had been taught in college.

I couldn't have been more wrong, or more uneducated. It makes me kind of embarrassed how little I actually knew. It wasn't until I read a venerable text called The Rise of the Novel by Ian Watt that I started to realize my mistake. Watt, writing in the 1950s, adheres to the conventional wisdom that the men I just mentioned were the only notable fiction writers of their time. Still, Watt’s book was helpful, especially in explaining how the birth of the novel as we know it was inseparable from early industrialization, urbanization, settler colonialism and the birth of a new (lower) middle class that read for pleasure. But Watt included one tiny stray footnote that referenced women writers of the era — and it sent me all the way down a research hole.

Guess what? There were plenty of women writing novels at the same time as Henry Fielding and Samuel Richardson. Henry’s own sister, Sarah, was a best-selling novelist and an incredibly influential writer and critic. Many, perhaps most, of the biggest names in literature in the 1730s and 1740s were women. And it's absolutely not true that Jane Austen was the first great woman novelist. They lied to me, y'all.

The research hole I went down was exceedingly deep. It led me to books like Mothers of the Novel by Dale Spender and The Professionalization of Women Writers in Eighteenth Century Britain by Betty A. Schellenberg, among many others. I found plenty of fascinating insights about the role of women in mid-18th-century society and the shifting gender norms of the time. I'm going to be writing a lot more about 18th century stuff in this newsletter over the next few months. (I'm very glad that the ARCs of Lessons in Magic and Disaster include my historical note with all my sources, because it's an essential part of understanding the context of the novel I eventually wrote.)

One thing that fascinated me about Samuel Richardson was his ability to write women’s POVs with extraordinary depth and sensitivity. His novel Clarissa is a strong contender for the greatest work of fiction in the English language, alongside Middlemarch and a few others. It’s an epistolary novel, meaning that it consists entirely of letters written by two of the characters, and it is about how women can be good in a world that scarcely rewards goodness. For years, I wondered how Richardson, a moralizing patriarch, had managed to write a female voice so well — until I realized that he’d hung out with Sarah Fielding and her best friend/life companion Jane Collier, literally all the time. Jane Collier was a governess to Richardson's children, and lived with his family while he was writing Clarissa. Both women gave him extensive notes on his work, and may even have helped him to revise it substantively.

So, back to the feud.

Richardson's smash hit debut was a novel called Pamela, about a maid whose employer is constantly harassing her and trying to coerce her into sex. The book has a happy ending: Pamela fends Mr. B. off for long enough that he eventually decides to marry her, and everyone admires her because her virtue has been rewarded.

Henry Fielding was annoyed by Pamela’s sexual moralizing. (It didn't help that he wrongly believed it had been written by his arch nemesis Colley Cibber, the father of Charlotte Charke, of whom we'll talk another time soon.) Fielding, who actually did marry him one of his maidservants, felt that Pamela was a hypocritical story that advocated for withholding sex in order to obtain material benefits. He wrote a parody called Shamela, in which a conniving maid manipulates her foolish employer into marrying her. Not satisfied with that, Fielding went on to write a longer work called Joseph Andrews, which is sort of a gender-flipped version of Pamela in which everyone is constantly trying to seduce the naive and gormless hero.

We don't really know how serious the beef between Richardson and Fielding ever got — by contrast with the spat between Fielding and Colley Cibber, which we know plenty about. Richardson definitely seems to have thought Fielding was an asshole, but the two men did exchange letters: I've read what survives of their correspondence.

What’s definitely true is that they got on each other’s nerves in ways that seem to have pushed them to create more interesting, better fiction afterward. Henry Fielding went on to write his masterpiece, Tom Jones — another book about a gormless dude, but this time with sharper comedy and a more fully realized character. And as I mentioned, Richardson went on to write Clarissa, another book about a woman trapped in an unthinkable situation, but this time containing a wittier and more self-aware heroine.

(Richardson seems to have been very concerned with the sexual double standard. His third novel, Sir Charles Grandison, is about a man who resolves not to lose his virginity until marriage, which was not considered proper male behavior at the time.)

What's weird, in any case, is that while Henry Fielding was doing everything in his power to piss Richardson off, Richardson was hanging out all the time with Henry's sister, Sarah. Richardson was a huge supporter of Sarah's work, helping her to find a publisher and even printing many of her books himself. The two of them appear to have had a deep and respectful friendship, built on mutual admiration. And Sarah's bestie, Jane, was living with Richardson as I mentioned earlier.

In any case, when you add Sarah, Jane, and all their contemporaries to the picture, things expand rather a lot. And in the end, my novel barely mentions either Henry or Samuel.

At the risk of oversimplification, both of those men wrote books that were largely about individual morality: personal foibles in Henry's case, the difficulty of remaining good in a corrupted world in Samuel’s. What I find compelling about the works of Sarah Fielding and Jane Collier is a stronger focus on community and inherently unfair power dynamics. (I know I'm at risk of imposing 21st century ideas on these 18th century women, but bear with me.)

Sarah's most famous novel, David Simple, is about a good-hearted man who nearly gets tricked out of his inheritance by an evil brother. He then spends the rest of the novel floating around London seeking a true friend, or someone who won't try to take advantage of him. He encounters a string of abusers and jerks, before he finally winds up with a few people who are as kind as he is, and they resolve to live harmoniously together for the rest of their lives — until the eventual sequel, where everything goes really dark.

Sarah also wrote what's often described as the first young adult novel in english, The Governess. A gaggle of teenage girls go from selfish and mean to kind and harmonious thanks to some wise instruction from their School mistress, Mrs. Teachum. (She also tells them some pretty wild fairytales along the way.)

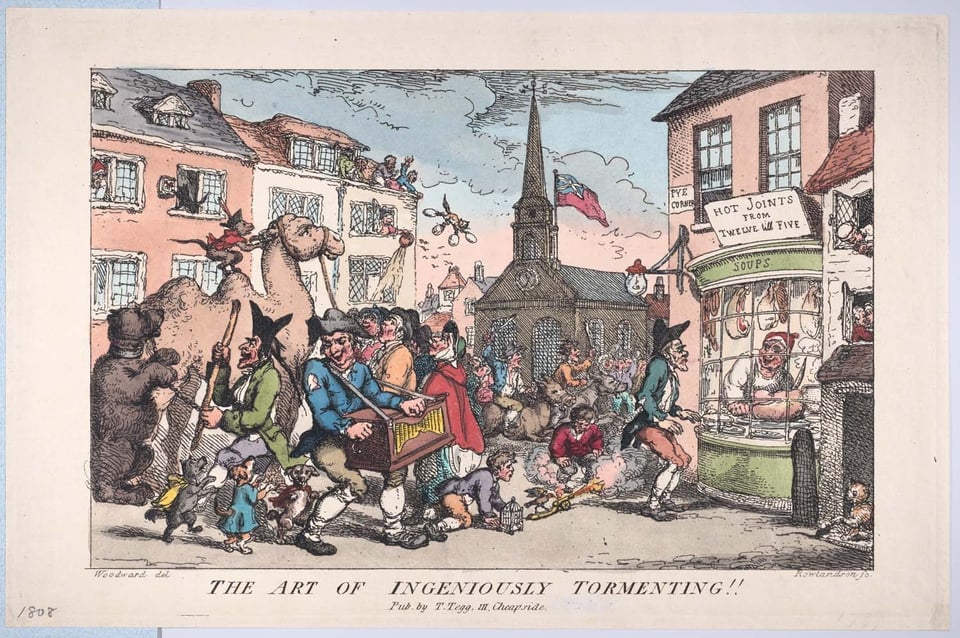

Jane Collier, meanwhile, wrote a savage satire — way more biting than anything Henry Fielding ever managed — called The Art of Ingeniously Tormenting. This is just what it sounds like: a handbook on how to abuse anybody you have power over. The bulk of it is about how to abuse your servants, your children, your spouse, your friends, and the unmarried women who are forced to live with you as companions.

It's also believed that Sarah and Jane collaborated on an experimental metafictional novel called The Cry, in which a young woman tries to tell her life story but is constantly interrupted by a crowd of hecklers who deliberately misinterpret everything she's saying and accuse her of all kinds of hypocrisy. Basically, social media.

So you can see why I became fascinated with Sarah Fielding way more than her brother Henry, and with Jane Fielding rather than her employer Samuel Richardson. Add the fact that these two women never married and seemed to be pretty inseparable, and their proximity late in life to a famous scheme to create a woman-only utopian community, and I was well on my way to becoming obsessed. Needless to say, learning about these two authors and other fascinating women of the mid-18th century ended up changing Lessons in Magic and Disaster — entirely for the better, too.

I can’t wait to tell y’all more about what I’ve learned about the amazing ladies and gender-nonconforming folks of the 1730s and 1740s. Watch this space!

Music I’m Listening to Right Now

I interviewed trans singer Ryan Cassata back in 2018 for a Teen Vogue article. Now he’s got a new song out called “i feel like throwing up,” which is pretty explicitly about what it’s like to be a trans person in 2025. It’s catchy as hell and feels pretty darn real. And the music video starts out pretty dark, but builds to a fist-pumping, upbeat conclusion as trans people come together to support each other. Check it out: