I'm So Inspired By These Brazen Women From 300 Years Ago

The Sixties saw the beginning of a long period of glorious liberalization. Women gained more rights and outlets for self-expression. Art and literature started to challenge conventional norms and gender roles. For about sixty years, this seemed like the new normal. People started to take this liberalization for granted — and then society clamped down again, with a return of theocratic repression and authoritarianism.

I am, of course, speaking about the 1760s and the period of liberalism that ended in the early decades of the eighteenth century. (What, did you think I was talking about something else?)

My upcoming novel Lessons in Magic and Disaster has a subplot involving queer women writers and artists in 1730s and 1740s London. To research that book, I read a humongous pile of books:

I also talked to some scholars over Zoom. One of them was Elizabeth Knauss, who teaches at Gwynedd Mercy University and wrote this amazing dissertation about “Breeches and Travesty Roles” in England between 1660 and 1737. And Knauss helped me make sense of the context of this era.

Basically, prior to 1660, England was under Puritan rule following the execution of King Charles I in 1649. There was no music and no fun at all during that Puritanical era, until the monarchy was restored in 1660 and everybody had to party twice as hard. The theaters were reopened and there was a “libertine environment,” as Knauss put it. The rules for women in particular were loosened a lot, and women were encouraged to be much more free and enjoy themselves.

Inevitably, there was a backlash as people started to put more emphasis on female chastity and good behavior, and women were encouraged to behave more modestly and avoid even the hint of scandal — this culminated in the Licensing Act of 1737, which shut down all of the theaters apart from a few officially licensed ones.

During the Stuart Restoration and the early Georgian era, gender roles were also much more fluid, especially on stage. In her PhD thesis, Knauss mentions a startling statistic:

John Harold Wilson calculates that, of the 375 newly produced plays between 1660 and 1700 in London, eighty-nine of them contain a breeches role. Nearly a quarter of all new plays in a forty-year span portrayed a female actress masquerading as a man for some reason or other.

Besides “breeches roles,” in which female characters pretend to be men (think Viola in Twelfth Night), there were “travesty roles,” where a woman plays a canonically male character on stage. According to Knauss, there were even a number of “all-female productions” (in which every role, male or female, was played by a woman) during this period. Considering that until the mid-seventeenth century, women weren’t even allowed on stage at all, this is astonishing.

A lot of scholars back in the day used to insist that the popularity of breeches roles and travesty roles was due to the fact that they featured women wearing tight clothing, appealing to prurient male interest. But Knauss argues persuasively in her thesis that there’s more to the story: these on-stage narratives disempower women until they put on male garb, at which point they are able to seize control of their lives. Or as Hellena puts it in Aphra Behn’s 1667 play The Rover, taking off female clothing means letting go of a “dull” state of mind and replacing it with one that is “gay” and “fantastic.”

Who doesn’t want to be gay and fantastic? I mean, come on.

Aphra Behn was one of a bunch of amazing female writers: the author of the novel Oroonoko and a ton of “scandalous” plays. Forced into debtor’s prison because Charles II wouldn’t pay her the money he owed her, she vowed never to depend on anyone else financially and became one of the most high-profile playwrights of the era for the next twenty years until her death. As Susan Staves writes, Behn’s best playwriting “combines skill in plotting intrigue comedy with skeptical questioning of conventional views of sexuality and morality.” Here’s a great article calling Behn’s play The Amorous Play “the #MeToo play of the 17th century.”

But there was also a whole circle of (proto) feminist writers and thinkers. Including Mary Astell, who advocated for the education of women in her 1694 book A Serious Proposal to the Ladies and criticized inequalities in marriage in her 1700 book Some Reflections Upon Marriage. (She also wrote a lot about theology and the nature of consciousness, in dialogue with other writers like Descartes.) And I already talked a while back about Astell’s contemporary, Lady Mary Chudleigh, who wrote some extremely barbed poems about men and the institution of marriage. Meanwhile, Catherine Trotter Cockburn was a leading philosopher and defender of John Locke.

Aphra Behn is often described as being part of a trio of scandalous female writers during this era, the other two being Delarivier Manley and Eliza Haywood. (I have a biography of Manley sitting on my shelf, but haven’t gotten to read it yet, and meanwhile there’s a biography of Haywood from the same series, which is sadly outside my price range.)

Staves describes Manley as someone who was determined to “continue the Restoration libertine tradition of Behn”. Perhaps because Manley had gotten “tricked or seduced” into a bigamous marriage with her own cousin, she set about creating sympathetic portraits of other women who had lost their chastity, starting with her first book The Lost Lover, or the Jealous Husband in 1696. Manley became known for her “scandal chronicles,” which is just what it sounds like. Manley was a fierce defender of the Tories and used some of her scandal fiction to take down members of the Whig party. After the 1709 publication of her best-known work, The New Atalantis, Manley was briefly arrested under a law targeting scurrilous or libelous works.

Haywood, meanwhile, had a fascinating career — she was an astonishingly prolific writer, who “dominated the market for amorous fiction” in the 1720s according to Staves. Haywood started out as an author of scandal chronicles, similar to Manley, along with novels that celebrate female desire and explore how love can be either sacred or profane. She also wrote a series of short tales in the 1720s about clever women who exploit men’s desires for their own gain. The British Recluse (1722) is about two women, whose lives were destroyed by the same man, decide to live together and take care of each other. The Fruitless Enquiry (1727) is about a woman who castrates her man who raped her. Still, Staves points out, these stories often reinforce stereotypes of women as “uncontrollably avaricious, vengeful and lustful.” Haywood was also an actor and playwright, which meant hanging around with sex workers and other disreputable sorts.

So Haywood was well known as a writer of saucy, scandalous tales — until she wasn’t.

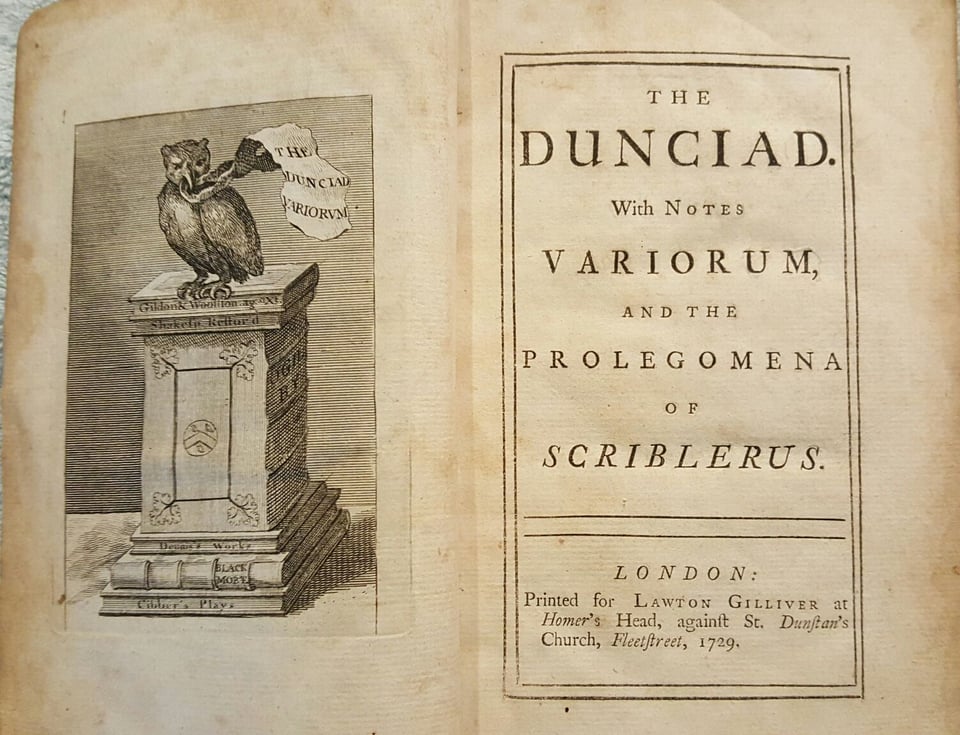

After Haywood was attacked by Alexander Pope in his cruel satirical poem The Dunciad, she changed gears. She stopped writing about love and scandal, and instead started turned to novels that advocated virtuous behavior on the part of women. She also started writing “conduct books,” which were full of advice to women on how to behave with propriety, sprinkled with short narratives to illustrate the main points. Haywood also founded a magazine called The Female Spectator, which ran from 1744 to 1746 and is often claimed as the first magazine published by women for women — but it mostly offered advice on good behavior. “Haywood was right to think that dispensing advice on domestic life was going to be one of the provinces in which women’s writing would be accepted,” Staves writes.

Times had changed, and women’s writing had to change with it.

The 1730s were a fascinating time overall — the printing press was becoming easier to access and reading is being democratized. Technology was improving, Britain was growing wealthy thanks to colonies and settler colonialism, and a Puritan work ethic took hold. But that soaring wealth and increased access to ideas and information did not go hand in hand with greater liberalization — instead, women were being pushed back into the domestic sphere.

(This is part of what was going on in the famous rivalry between Henry Fielding and Samuel Richardson — Richardson advocated chastity and virtue in his novels, and Fielding felt this new morality was unrealistic and hypocritical, as Gary Gautier told me when we talked.)

So I’m especially obsessed with the most colorful, fierce women of the 1730s and 1740s. I already wrote about trashy memoirist Laetitia Pilkington and the wild exhibitionist Elizabeth Chudleigh. But there was also Hannah Snell, who disguised herself as a man and joined the Royal Marines — when she was injured, she dug some buckshot out of her own groin, so as not to give away her secret. (And when she was found out, she briefly became a celebrity and traveled around speaking to packed audiences.) And Mary Porter, an actress who fought off a highwayman single-handed, only to turn around and raise money for the highwayman’s family after he told her they were starving. (I talk about these ladies a bit in Lessons, because I couldn’t leave them out!)

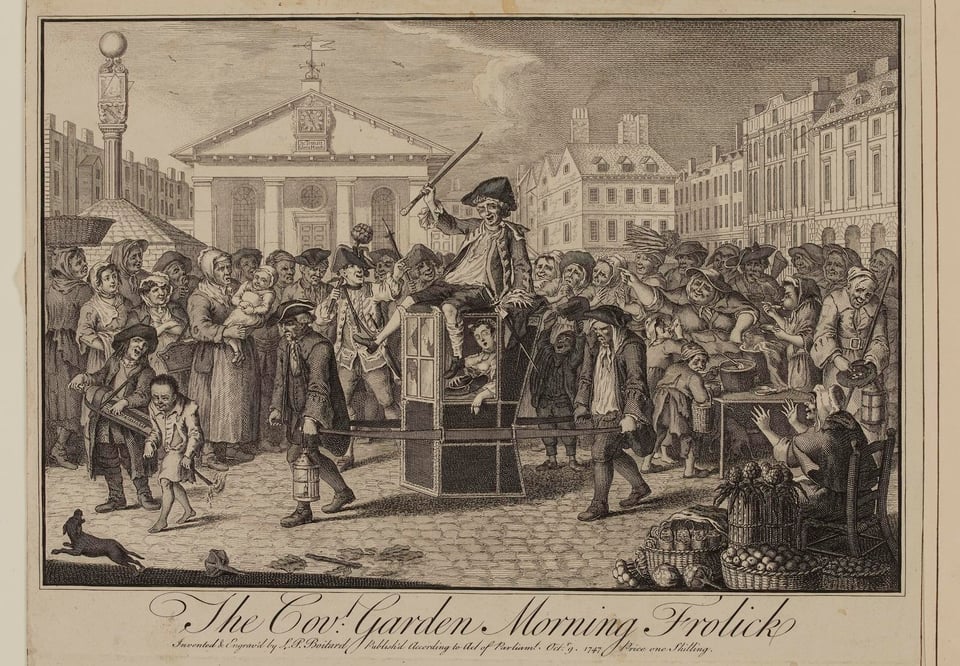

Then there was Betty Careless, a notorious sex worker and brothel-owner, who became a celebrity and literary figure. Here she is, dozing inside a sedan chair with the drunken Captain “Mad Jack” Montagu perched on top in the 1739 print “The Covent Garden Morning Frolick” by Louis Peter Boitard:

So I started off by talking about breeches parts and travesty parts, and I haven’t even talked about my favorite Georgian rebel yet. Charlotte Charke was the daughter of Colley Cibber, an actor, playwright and theater manager who became the Poet Laureate of Britain. I’m gonna write a whole thing about Charke soon — maybe even next week! — but for now, just know that she was dressing in her father’s clothes from the age of four. She played breeches roles and travesty roles all the time, making a whole career out of playing men on stage — including a parody of her own father that got her disowned. And when she couldn’t work as an actor, she lived as a man, doing jobs that were supposed to be reserved for men. She even had a wife, for many years, who is only known as Mrs. Brown. Charlotte Charke (who used she/her pronouns when she was alive) is a queer icon, who plays a small but significant role in Lessons in Magic and Disaster. As Knauss told me when we talked, Charke feels like a “chaos agent” who consistently challenged the oppressive new morality of her era.

But more on Charlotte Charke soon, I swear.

Anyway, it’s sort of inspiring that so many women managed to burn so bright during a time when repression was increasing — and I haven’t even gotten to the Bluestockings and their dream of creating a utopian all-female community modeled after Sarah Scott’s 1762 novel A Description of Millenium Hall.

A few things come to mind, though. Some of the women who were most successful at making their own way in Georgian England had been briefly married to men who died or disappeared, giving them the status of married women without an actual husband to worry about. (This was true of Charke, Pilkington and Scott, off the top of my head.) Also, most of the women I admire from this era were constantly broke, going in and out of debtor’s prison and reliant on the generosity of wealthy men for their survival. Jealous bitches like Alexander Pope were always ready to tear down women writers and artists. It was by no means easy or comfortable to defy convention as the Georgian era grew more repressive.

This only makes me admire the women who clawed out a place for themselves in literature and the public sphere all the more, however. I find it especially inspiring, as we live through our own period of deepening theocracy.

Hey, if you liked this free newsletter, please please please check out my upcoming novel Lessons in Magic and Disaster, which is about families, queer liberation, and the search for the truth about a strange novel from 1749.

More info about the novel and my bodacious pre-order campaign are here.

I’m going on book tour! Including Green Apple on the Park, Powell’s, Women and Children First, North Figueroa Bookshop, Third Place and Charis Books. Details of all my events are here.