I Can't Stop Writing About Violence

Hi! My book Lessons in Magic and Disaster has been out for a month, and I’ve been blown away by the response so far. So many people have told me that my fantastical mother-daughter story has made them cry or spoken to something in their own lives. I loved this review in Cannonball Read, where Emmalita calls Lessons “an achingly beautiful book” and talks about how personal her response to it has been. You can order Lessons everywhere! You can get a signed/personalized/doodled copy at Green Apple.

This Saturday, I’m going to be at Marin MOCA for Feminist Futurism vs. Project 2025 with Angela Dalton, Faith Adiele, Tamika Thompson and moderator Isis Asare.

Next Weds 10/1, I’ll be at Pegasus Books for Bay Area Sci-Fi Wizards, with Sarah Gailey, Susanna Kwan, Annalee Newitz and Lio Min.

On Thurs 10/2, I’ll be at Cafe Suspiro for the Stir reading series.

I keep trying to make sense of our violent times

Violence has been a major theme in my work ever since, well, 9/11. In the aftermath of those attacks, I saw people driving themselves into a frenzy of violent retribution, and the marshaling of groupthink towards driving us into two foolhardy wars, and I felt like I needed to find some way to speak to this moment.

Nearly twenty-five years later, I'm still trying to find ways of talking about our love of violence as a species — and our obsession with using force to control people and reinforce our beloved hierarchies.

After 9/11

So yeah, I was freaked out and furiously angry in 2002-2003, watching all the militaristic posturing and the disingenuous drumbeat to war. I needed to find a way to talk about it.

At that time, I was also obsessed with writing comedy, including a lot of gonzo physical comedy. I loved watching characters try to maintain their dignity and sense of reality while slipping and sliding, knocking over everything in their path, careening toward chaos.

And I remembered something my dad used to say: he couldn't watch a Charlie Chaplin movie when he was a kid, because he found Chaplin’s brand of slapstick too sadistic. He felt like a lot of slapstick comedy, such as the Three Stooges, involves a certain amount of violence that is played for laughs because you are laughing at the person on the receiving end. (See also “splatstick,” where gory body horror is played for laughs, e.g. Dead/Alive.)

So that led to my novella Rock Manning Goes for Broke, which I started writing as a novel sometime in 2002. The story of a slapstick performer who gets swept up in a fascist takeover of the United States, Rock Manning felt like the perfect way to explore the intersection of slapstick comedy and real life violence, and the ways in which we can witness horrible atrocities being done to people as long as we can either laugh or dissociate ourselves from empathizing with them some other way.

The Society for Ethical Violence

In the novel-length version of Rock Manning, there’s an organization called the Society for Ethical Violence — a group of progressives who argue in favor of using violence to make the world a better place. They claim to hate violence, but have decided that it’s impossible to avoid because it’s part of human nature and therefore ought to be harnessed for good. The leader of the Society for Ethical Violence is a charismatic older white guy named Guthrie Hirsch who rose to fame as the next Howard Zinn.

In this version of the story, Rock has a girlfriend named Carrie who falls into Guthrie’s orbit. And Rock is almost sucked in as well:

Carrie said it all made sense when Guthrie talked, and he could look straight into you and see not just the hurting part, but the part that wanted to hurt others. He could make you feel safe from yourself. What had happened to Guthrie during that year or so he was missing, nobody knew, but he'd come back ten years older and with twice as much energy.

The leaflet showed him, eyes glowing, long gray beard with no mustache, one leather fist up. It said our potential for physical aggression was the engine that built civilization, which then turned around and tried to repress that potential, and that's why civilizations fail. So we could save our civilization if we reclaimed our love of violence. …

"We talk about the social contract," Guthrie Hirsch said when I met him a few days later, "but people forget, all contracts are enforced. Meaning, we use the threat of force to make people honor them." Blah blah blah. It was like being back at school, except we were outdoors and there was no desk for me to set on fire by accident.

I was sad to lose Guthrie Hirsch when I turned Rock Manning into a novella, but for various reasons neither he nor Carrie quite fit anymore. And I’m glad I revised Rock Manning and was able to release it at last, because its depictions of fascism were becoming more and more relevant.

Still, that stuff about “contracts are enforced” feels like it’s laying down a theme that’s come up in my work ever since: violence is baked into all of our systems and we are so used to it that we’ve stopped seeing it. A couple of other more recent examples feel especially relevant just about now.

My novel The City in the Middle of the Night includes a character named Mouth who is a self-proclaimed bruiser. In fact, I make a huge point of showing from early on how Mouth’s internal monologue classes with the story she tells about herself. In her very first chapter, she's boasting about taking down a group of thugs who tried to rip off her smuggler crew, but meanwhile her inner monologue is endlessly worrying about whether all of that killing had really been necessary and whether she could justify ending those lives. Mouth comes from a spiritual background, and has never fully accepted the kill-or-be-killed ethos of the smugglers she’s joined.

Later in the book, Mouth has a kind of breakdown, and finds that she can no longer do violence. She freezes up when she reaches for a weapon or tries to make a fist. She still wants to protect her beloved Alyssa, but has to find ways to do it without hurting anyone. The dilemma of being thrust into violent situations without being able to commit violence felt really interesting to me, but so did the visceral disgust towards violence and the self-loathing that comes with it, which force Mouth to become a pacifist.

I basically explored the same notion a second time in my young adult books. (It’s only hitting me now just how much I was exploring some of the same territory in a different way.)

Victories Greater than Death is about a teenager named Tina, who is secretly a clone of the galaxy's greatest hero, Captain Argentian. Tina is supposed to get all of Captain Argentian's memories, but the process fails and she's left with only the Captain’s skills and knowledge. Tina is desperate to prove that she can live up to the legacy of this legendary hero, and that longing powers the entire first book of the trilogy.

When I was writing Victories Greater than Death, I had a pretty solid outline that involved a lot of space battles and fighting. Somewhere in the middle, I decided to write a bunch of short little adventures that Tina and the rest of her starship crew could go on, so Tina could bond with her shipmates and get some experience. When I was writing a bunch of those little vignettes, I wrote one scene where Tina kills some bad guys for the first time — and I hadn't consciously anticipated what that would be like.

The process of ending someone's life — watching them transform in real time from a person with opinions and ideas and joys and pain to just nothing — is overwhelming. Tina goes into a tailspin, and by the end of the first book, Tina has reached a decision: she vows never to take a life again. Needless to say, this was one of the things that torpedoed my carefully laid plans for the second and third books of the trilogy.

But it also opened up a lot of interesting story lines that I hadn't expected. The third book of the trilogy, Promises Stronger than Darkness, culminates in a huge dilemma: do we kill a few thousand morally compromised people to save the galaxy? Tina just forced to wrestle with this choice, and — spoiler alert! — only figures out another alternative at the last possible moment.

What I believe

Writing these books definitely forced me to think a lot about where I stand with regard to violence. I have a deep and visceral revulsion toward the notion of committing violence, and I sure as heck don't want to be on the receiving end of it. I'm not sure that I'm an absolute pacifist — if I were under attack by genocidal maniacs or invading imperialists, I might not have any choice but to take up arms. My objections are at least in part emotional rather than moral.

But I do believe that violence is disgusting and shameful. Sometimes you have to do revolting things to survive, but you don't brag about them or glorify them, and you try like hell to avoid doing them. That's my baseline belief, I think.

Coming back to what Guthrie Hirsch says about the social contract, I also think that there are a lot of things that we don't consider violence, which are actually quite violent.

Probably the most the second most quoted line in The City in the Middle of the Night is when Mouth says:

Part of how they make you obey is by making obedience seem peaceful, while resistance is violent. But really, either choice is about violence, one way or another.

Combine that with what Guthrie Hirsch says about the social contract, and that sums up a lot of stuff.

Society runs on violence, and no aspect of society can function without it. Taxation is the government taking your wealth from you by force, with the threat of imprisonment if you fail to comply. Most of us are aware on some level that there are forms of behavior that are intrinsically harmless to others, but which will expose us to the to a high risk of violence if we engage in them. Until recently, being openly trans was punishable by violence almost everywhere, and it still is in many situations.

Lessons in Magic and Disaster isn’t as explicitly about violence, but my protagonist Jamie has an epiphany in the latter part of the book, that she’s been committing a kind of violence against her partner Ro by trapping them in a story they didn’t choose. Jamie reflects:

If forced imprisonment is a form of harm, then trapping someone in a toxic narrative could be considered an actual assault.

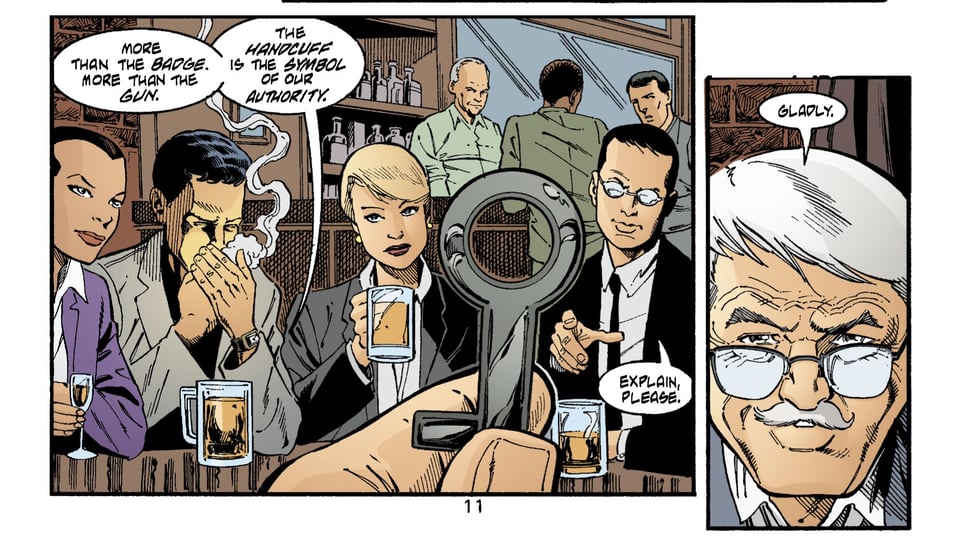

I think often about Batman #587, written by the always essential Greg Rucka with art by Rick Burchett and Rodney Ramos. The cops throw Commissioner Gordon a birthday party and he rewards them with a lecture about why handcuffs are the ultimate symbol of police power:

Gordon goes on to say, “We are the only people in this free nation who have the power to deprive a citizen of their freedom. Of their liberty. The only people with the authority to hold them against their will.” The power of arrest is the most awesome weapon in a cop’s arsenal, even more than a gun.

When people decry the horribleness of political violence, what they're really saying is that they want those who have been designated by the state to have a monopoly on the use of violence. Or perhaps, that those who have been committing violence with impunity for decades should continue to have a monopoly on it.

So… I'm super interested in questioning the necessity and usefulness of violence — when is it justified to fight back?

But I'm also increasingly interested in exploring how violence is embedded in every part of our world, from law enforcement to the sheer brutality of late stage capitalism. And the extent to which we pretend that we're not participating in violence when we clearly are, but we also treat certain kinds of violence as natural and praiseworthy.

We are all the Punisher

Lately, I keep thinking about that punishment is such a huge part of our worldview — to the point where many religions include some aspect of supernatural punishment for wrong actions. Either reincarnation into a form that causes suffering, or unending torture in a cosmic barbecue pit. When people say that they don't believe you can be a good person if you do not believe in God, I feel as though they are really saying that they don't believe people will behave decently without the threat of punishment.

It's not just that we encourage people in uniform to mete out brutality on our behalf. It's not just that we know on some level that our whole economy is built on mistreating people. It's also that deep down, we believe that all good behavior comes from the existence of a supernatural torture chamber. This is the backdrop against which we ask ourselves if violence can be justified. Until we’re honest about how much our culture sees violence and punishment as essential and beneficial, then our conversations about violence will always be carried on at the level of peevish little children.