Hope Is Important, But So Is Curiosity

As always, this newsletter is free — but please pre-order my upcoming novel Lessons in Magic and Disaster. It’s a strange, tender mother-daughter story about a young witch who decides to teach her heartbroken mother how to do magic. There are flashbacks to the mom’s past as a lesbian activist in the 1990s, and a Dark Academia subplot about uncovering the secrets of a mysterious queer book from 1747. Nicola Griffith calls it “a hymn to queer love, joy, and persistence… A book for our times — and for all the times before this.” You can pre-order it anywhere, but if you want it signed and personalized with a doodle, you can get it from Green Apple Books in San Francisco.

Also! I’m super proud of the latest episode of the podcast I co-host with Annalee Newitz, Our Opinions Are Correct — it’s about why so many tech billionaires really believe we are living inside a simulation. (Just like the Matrix.)

We need hope, but also curiosity

I talk and think a lot about how to keep hope alive during a time when hope feels like one hell of a stretch. But lately, I've also been thinking about how to stay curious.

Curiosity feels super important to me for a bunch of reasons. It keeps the world big — full of discoveries I haven't encountered yet. It reminds me that there's so much I don't know, including plenty of things that complicate a doom-and-gloom perspective on reality. Staying curious also feels like a way to be different from the people who want to destroy me, whose defining trait seems to be that they've made up their minds and don't need to take in any information that might contradict their worldview.

In a lot of ways, I've started thinking of curiosity as the opposite of depression, in much the same way that hope is the opposite of despair.

When I am learning new stuff, I feel excited and eager — I feel hungry — and I can feel my brain light up as I take in new information and absorb new perspectives. I feel receptive, engaged. On days when I can't bring myself to be curious, or I'm too stressed and overwhelmed to learn anything, that's when I tend to feel like hot garbage.

So making time for finding out new stuff is increasingly an important part of my practice, even though it's really tough when my life gets completely hectic. I’m also drawn to other people who are excited to tell me about the latest thing they’ve just learned, which is one thing I love about hosting the Trans Nerd Meet Up every month.

I'm not necessarily talking about a kind of curiosity that's going to lead directly to inspiration in the fight against authoritarianism and fascism. That can be incredibly valuable, but in my experience, it also leads me right back into fight-or-flight mode. I can't obsess about the struggle without thinking about why I'm struggling. In some ways, I can often get more inspired by stories of resistance and resilience when they aren't quite so closely related to the situation we're in right now.

For example, the other day I was hanging out with my friend Marley, and she recommended Sarah Schulman's recent book Let The Record Show, a history of ACT UP New York from 1987 to 1993. It talks a lot about the direct action that queers were doing during a moment when the United States government was refusing to take the threat of HIV and AIDS seriously. I've started reading this book myself, and it's just far enough away from the problems of 2025 that I find it both fascinating and thrilling, without getting sucked into thinking about the slimy creeps who are slithering inside our government right now.

It sounds counterintuitive, but learning something about the history of ship-making or ancient funeral practices can be better for my fighting spirit than yet another resistance newsletter. Once I've soothed my mind and remembered that this world is huge and full of weird facts, past and present, I have a little bit more perspective and can get back into the fight, in whatever way I'm capable of. I guess I'm talking about self-care, at least in part.

Last year, I interviewed Isaac Fellman about last year about how to be an archivist, and that feels like a related topic. We definitely all need to be archiving and preserving queer books and materials, along with so much else. (The government’s recent attempts to memory-hole critical resources and information about marginalized people only underscore the importance of this.) But keeping materials safe is only half of the story — if you're not also feeding stuff into your own brain and storing it in your squishy bits, then your archive is merely a set of banker’s boxes and hard drives gathering dust, with no guarantee that anybody will ever look at any of it. This information needs to be a living thing, which means it ought to live in you (as much as you can manage.)

Anyone who's read my book about writing as a means of self-preservation, Never Say You Can't Survive, will know that curiosity is also a huge part of my creative practice. It's the main way I generate stories: becoming curious about characters and situations, and following the threads to see where they lead. I don't believe in writer's block, but one of the things that people mean when they refer to being blocked is simply a lack of curiosity. All too often, if I can't move forward with my writing, it's because I'm no longer curious to find out what happens next.

I used to hate doing research for my fiction because I saw it as too similar to journalism — the other kind of writing that I've done for money. I used to think the point of research was making sure people wouldn’t yell at me about getting facts wrong in my fiction — you said they took the 6:45 train, but that train actually leaves at 6:37! — and I was always worried about getting so bogged down in facts that my imagination would no longer have any room to maneuver.

But of course, the opposite happened. I’ve found over and over again that the more information I take in, the more things start to feel real and concrete and the more they come to life in my mind. Because the research is about priming the pump of my imagination by feeding it some images and specifics that I can latch on to. This feels super basic, but it came as a huge surprise to me. (I've written about this before, rather a lot, but this goes double for when I'm writing about people from other cultures and backgrounds — those characters take on a much greater life and become much more fascinating to write, once I have done some legwork to fully appreciate where they come from.)

The goal is mental flexibility — keeping your brain from going into an endless feedback loop in which you chew over facts you already know, especially if those facts are telling you that the world is screwed. It's also about remembering to be surprised, which is a delightful experience (as long as the surprise isn't a bag of poop on your doorstep.)

I get a lot of this same benefit from reading really good fiction. Most days lately, I set aside at least an hour to 90 minutes for reading a novel in bed, which is great for relaxing but also for opening my brain up and nudging it off of various negative cul-de-sacs.

I want to finish by talking about a few of the things that have been feeding my curiosity lately.

I recently was lucky enough to tour the Museum of Arcade and Digital Entertainment (MADE), a playable museum in Oakland crammed full of classic and recent video games. I learned a ton about the evolution of home video game systems and arcade games, including the earliest versions of Pong. I had no idea that the first ever home game system, the Magnavox Odyssey, didn’t contain a processor or memory. The cartridges weren’t ROMs, like with the Atari or other later consoles, but instead just flipped switches inside the console to activate different games. You could put colored plastic overlays over your TV screen to change the “graphics,” which otherwise were just white squares against a black expanse.

Also, I am loving The Doctor Who Production Diary: The Hartnell Years by David Brunt. Brunt managed to get access to all the paperwork on the making of Doctor Who from 1963 to 1966, the earliest years when people endlessly debated whether the show could last another 13 weeks or just be canceled immediately.

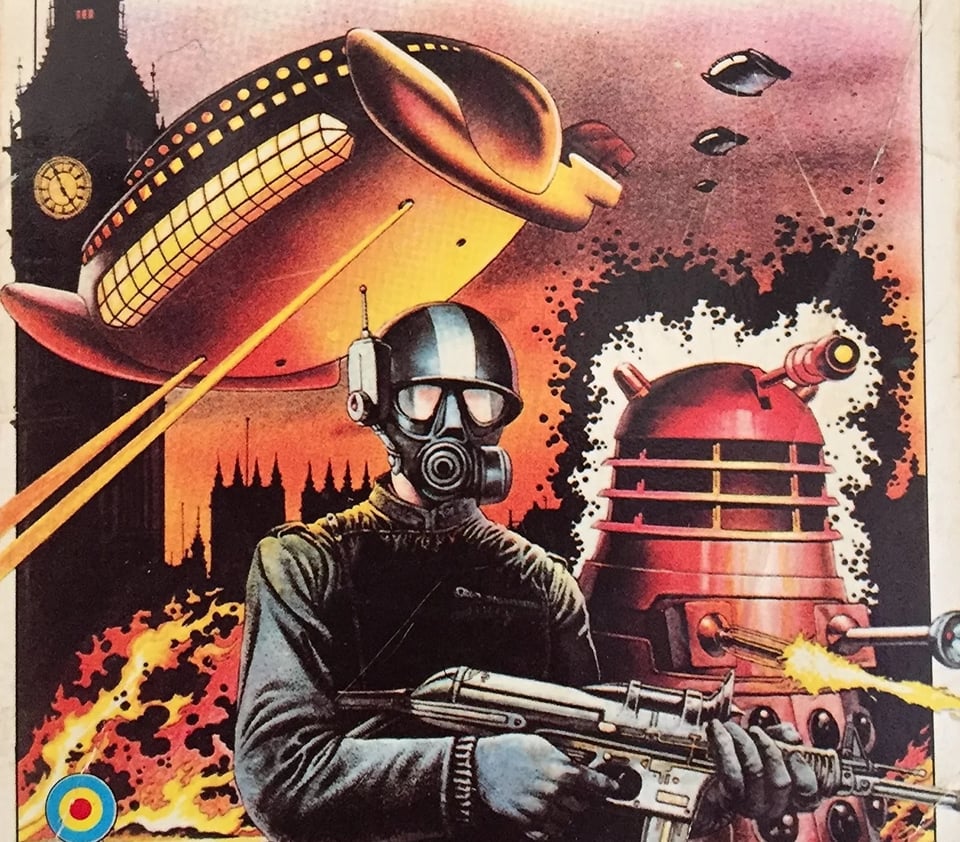

I've just been reading about the turmoil the Doctor Who team went through in 1964, around the time they were making "The Dalek Invasion of Earth." This is a super important story, because it's where the Daleks really cement themselves as epic villains — but also because it sees the show's first departure: the Doctor's granddaughter Susan leaves the ship, not entirely by choice.

I had never known that Terry Nation, the story's writer, had included a new character in “The Dalek Invasion of Earth” to replace Susan aboard the TARDIS. This would have been Saida, “a beautiful Anglo-Indian girl, who will eventually replace Susan.” At the end of the story, in Nation’s original scripts, the Doctor leaves Susan behind on Earth, only to be startled to find “a bright and smiling Saida” has snuck aboard the TARDIS. Imagine if Doctor Who had introduced its first BIPOC companion, over forty years before Martha Jones. Alas, the character of Saida was aged up and turned into a white woman named Jenny, who does not join the TARDIS crew after all.

Also, around that same time, William Hartnell, William Russell and Jacqueline Hill were all asking for money — and there was talk about either canceling the show or writing Ian and Barbara in the same episode as Susan. One BBC higher-up even suggested putting the show on a short hiatus and replacing the entire cast, including Hartnell, with new actors. This doesn’t seem to have gone far, but it still boggles the mind. Would the Doctor have regenerated in 1964, two years early? Or would they have found another way to recast the role? It’s hard to imagine.

Also finally, I've been dipping into Duane Tudahl's incredibly detailed guide to all of Prince's recordings in the mid '80s, released in two volumes thus far. I learned that Stevie Nicks wrote her hit “Stand Back” when she was on her honeymoon and she heard Prince’s song “Little Red Corvette” on the radio. She was inspired to write her own song, which shares a lot of DNA with “Little Red Corvette.”

But because she was a mensch, she got in touch with Prince and offered him 50 percent of the songwriting royalties. And she invited him to come into the studio to record some instrumental tracks on the song. As she puts it in the book, he “was absolutely brilliant for about twenty-five minutes and then left.” (Contrast this with Phil Collins, who heard "1999” and was inspired to write "Sussudio," but gave Prince zero credit or input.)

I love learning new stuff. It makes me feel alive.

If you’re in San Francisco tomorrow (Thurs, Feb 13), please go to the Mechanics Institute at 6 PM to hear Caro de Robertis and R.O. Kwon talk about their new books Palace of Eros and Exhibit and “the power of desire in writing.” It’s going to be extra awesome. Click here to register — use the promo code "valentine" to get tickets at the members’ rate of $5 each.

Music I Love Right Now

Bobby Rush is a blues/funk singer whose stuff I’ve liked a lot in the past. He’s got a new album coming out called Young Fashioned Ways, a collaboration with Kenny Wayne Shepard which I’m pretty excited about. While I was reading about that, I stumbled across a compilation called Chicken Heads: A 50-Year History Of Bobby Rush, which came out ten years ago. As the name suggests, it covers his career from 1964 to 2014, including 75 songs (about five hours of material), and you can get a digital copy for $20. I’m still working my way through it, and thus far I love about half of those 75 songs. (Which is still incredible value.) There’s only one song that I actually dislike — it’s the one with the fatphobic title, which I advise skipping.

It’s interesting to trace the evolution of Bobby Rush over the decades, from swampy mid-1960s blues to 1970s funk. His 1980s recordings generally aren’t my cup of tea, because he tried too hard to lean into synthesizers and drum machines in a way that didn’t quite click. And then his 1990s stuff is mostly pretty good again, and a lot of his mid-2000s stuff is fantastic. Anyway, it’s fun to get a deep dive into Bobby Rush’s entire career, and I’m ending up with a ton of new favorite songs. Probably my favorite track so far is his 2014 cover of Rufus Thomas’ classic jam “Push and Pull,” featuring both the Hi Rhythm Section and rapper Frayser Boy.