1975: The Year It All Changed For P-Funk

A few months ago, a friend asked me what was the greatest funk album of all time. I didn't hesitate: I immediately named Mothership Connection by Parliament.

So I was excited when I saw that Daniel Bedrosian had written a book about Mothership Connection, and the year that led up to it. In 1975, Parliament released two iconic albums: Chocolate City and Mothership Connection. And their sister group, Funkadelic, released its best album, Let's Take It to the Stage. Bedrosian's new book, Make My Funk the P-Funk, talks about that year, and how George Clinton took his budding empire of oddballs and musical geniuses to a whole other level.

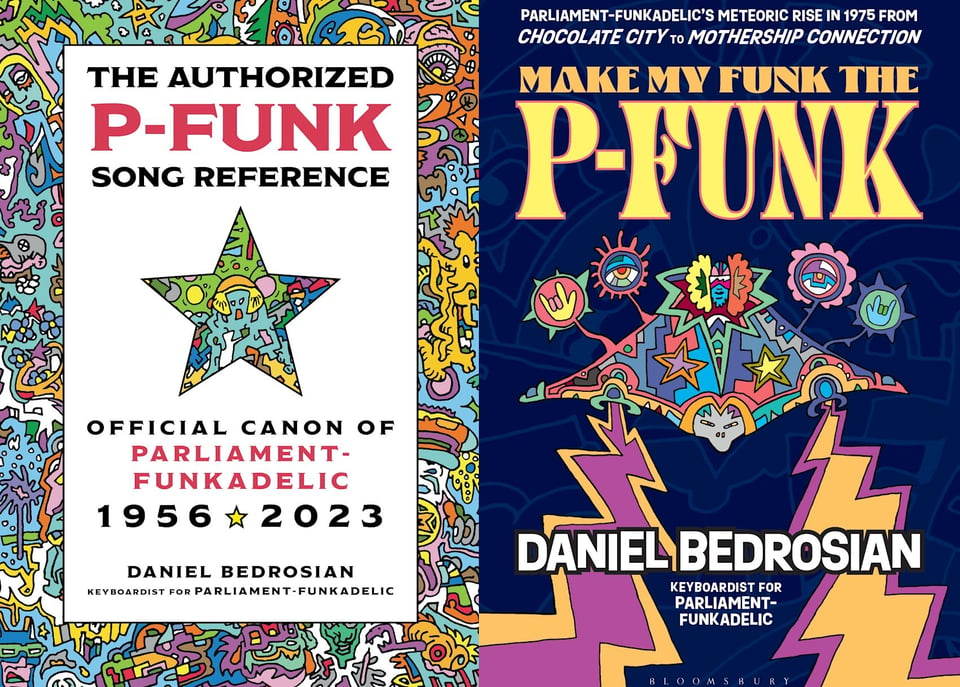

Bedrosian was the perfect person to write this book: he's been the keyboard player for Parliament-Funkadelic for half a century, working closely with most of the musicians who made those three albums happen. He also wrote an utterly indispensible reference guide a while back called The Authorized P-Funk Song Reference, an exhaustive guide to every major release that involved the core musicians of the P-Funk Mob. So I was excited to get the chance to chat with Bedrosian about the year that changed everything for P-Funk.

Why is Mothership Connection the greatest record?

Mothership Connection represents the "high water-mark of P-Funk," says Bedrosian. "It truly suggests a new theme for George [Clinton]. You know, he was constantly continuing to elaborate on previous ideas and experiment with new ones." But with Mothership in particular, "everything is kind of a right place, right time type of situation. You know, starting from the top down."

It starts with the record company that had signed Parliament: Casablanca Records. Founder Neil Bogart believed in the band enough to provide a bigger budget, and to "say yes to George's seemingly outlandish but utterly successful ideas." Bogart would go on to fund the ridiculously ambitious P-Funk Earth Tour in 1976-1977, including sets designed by Broadway legend Jules Fisher and a full-sized Mothership prop that descends onto the stage in an emotional climax.

Mothership Connection also boasts the right combination of musicians. By 1975, Bedrosian says, Funkadelic had won a reputation as "the live band that nobody wanted to mess with." To those seasoned musicians, you add some newly-arrived veterans of James Brown's band, the J.B.'s. And then there's the growing confidence of long-time P-Funk keyboardist Bernie Worrell. It's a perfect mix.

Add to that George Clinton's development as a producer, having already tried a lot of experimentation with previous albums. The earliest Funkadelic albums "were doing the things that hadn't been done," says Bedrosian, "until they felt like they had gotten a lot of that out of their system."

Bedrosian actually believes the band's "true creative peak" is the record before Mothership Connection, Funkadelic's Let's Take It to the Stage. But really, all three of P-Funk's 1975 albums are powerful enough to justify writing a book about this turning point in the band's history. Bedrosian painstakingly explains the band's development, who played what instruments on each track, and the inspiration for each individual song. He also puts the whole thing in the tumultuous context of the mid-1970s — a time when everything was changing.

1975 was a turning point in music overall

At the start of 1975, Parliament-Funkadelic had a cult following, and was the opening act for more mainstream bands like the Ohio Players. By 1976, they were ready to headline their own massive tour, with acts like Sly and the Family Stone opening for them.

And 1975 was a transitional year for music in general. Stax Records went out of business, and James Brown begins to fade. Disco became a recognized music genre, gaining its own Billboard chart at the end of 1974. A whole era of psychedelic rock and genre-defying pop music that began around 1967 came to an end around that time.

So 1975 could have easily been the year that Parliament-Funkadelic faded away, as so many other similar bands did. Instead, they were able to take advantage of the musical shifts happening that year, and fuel themselves to become a major act. How did this happen?

Bedrosian says it starts with George Clinton's skewed "version of what's commercial," which is "so far far afield from your average music writer's idea of what is considered commercial." Later, in 1978, Clinton released his most "bubblegum" pop record of all, Funkadelic's One Nation Under a Groove — which was also Funkadelic's biggest hit — and it's weird as hell. Clinton's notion of pop music is "ahead of its time," bringing together a lot of different sounds.

A good example of this is Parliament's monster hit, "Give Up the Funk (Tear the Roof Off the Sucker)," Bedrosian says.

George was trying a couple of things that he had heard. And he's translating those things he heard, and to him, it's exactly how he heard them. But because of his unorthodox style — be it compositional style, arranging style, production style, singing style, any of those things — it comes off in this way that sounds utterly unique, and like nothing you've ever heard before. Although, to him, it sounds like this pop thing that he's trying to nab and, like, trying to really, like, get at. But to us, there's nothing hackneyed, nothing derivative. To the rest of us who are listening to it, we're like, this is, like, something I've never heard, you know?

"So it's just that he's got kind of a weird sensibility in his attempts to be mainstream," adds Bedrosian. "It definitely gets more slick in '75 — like, the sound gets more slick. But it's slick in a weird way." Clinton's production on all three 1975 albums is much cleaner than his earlier works, but there are still a lot of dark, nasty, jazzy tones on songs like "P-Funk (Wants To Get Funked Up)".

Also, these albums feature Bernie Worrell working wonders with a new instrument: the ARP Pro Soloist synthesizer.

Why was the ARP so important?

Bedrosian, a keyboard player himself, devotes a lot of space in his book Make My Funk the P-Funk to the ARP synthesizer, interviewing Dina Pearlman, the daughter of inventor Alan Robert Pearlman. In the book, he explains how the ARP was a game-changer for music, including the number of different tones you could make with it. And the ARP String Ensemble could sound like a synthesized version of string section.

"People talk about the Moog [synthesizer], but [Bernie Worrell] wasn't playing the Moog yet at this point," says Bedrosian. The ARP became big with musicians earlier on, and "there were several ARPs that were built before a lot of the Moogs that became the most popular ones: the Mini Moog, and things like that."

"No album before Chocolate City has the ARP String Ensemble," adds Bedrosian. "With those string sounds, the whole sound of P-Funk is changing now, you know? Then with the synthesizer tones, all the crazy bubbly, liquidy, and stabby, and scissory, you know what I mean? These crazy tones, they come from the Pro Soloist. You start hearing that all over Let's Take It to the Stage." Those weird synthesizer noises become "iconic trademarks of the Bernie Worrell pallette, for all times." Other synthesizers come and go, but Worrell "never took [the ARP] out of his rig," says Bedrosian.

These ARP synthesizers came on the market around 1972, and you can hear the Pro Sololist on the Ohio Players's classic song "Funky Worm."

Bedrosian says the iconic synth part on "Funky Worm" is the Pro Soloist's "oboe" sound, "with the Portamento [feature] turned all the way up." When you hear the slide from low to high, the worm coming out of his hole, that's the Portamento struggling to catch up to the notes that Walter "Junie" Morrison is playing.

A singer was playing the drums

Most P-Funk fans know that 1975 was the year legendary drummer Jerome “Bigfoot” Brailey joined the band. Everyone had believed that Brailey played the drums on every song on Mothership Connection. But nope! Apart from “Give Up the Funk,” the songs on Mothership Connection generally feature drumming by Gary “Mudbone” Cooper, who is almost entirely known as a singer. Cooper told Bedrosian he’d never even owned a drum kit.

Clinton had “the wherewithal, on a production level,” to see how different players had different types of rhythm, says Bedrosian. “Mudbone had this really consistent, steady kind of pocket that didn't waver. He was just straight with it. And he played percussion, you know, Muddy always did this tambourine stuff that was super dynamic, and extremely intricate.” So Clinton saw him playing tambourine on stage and figured he could play drums, too.

Even Mudbone Cooper himself didn’t ever expect to be a drummer, but “he went on to be one of the most important drummers in the P-Funk canon,” says Bedrosian. “That's him on ‘Aqua Boogie’. That's him on ‘Atomic Dog’!”

“A lot of times, too, some of these drummers — not all, but some — were trying to get too fancy. And George is trying to get somebody who can just hold a pocket,” says Bedrosian. “The record is more important than someone's virtuosity.” Especially for musicians from Detroit, where Clinton cut his teeth in the 1960s, the perfect record isn’t necessarily one with a showy drum part.

Adds Bedrosian:

I'm a keyboard player who knows how to play a little bit of drums. I just play a gutbucket beat. There have been times where I've been chosen over real drummers to do tasks in studios, and not just in P-Funk, you know? So this kind of thing happens more often than most people would think.

This is also why drum machines became so popular later on, adds Bedrosian. “It's not because the technology is there, it's more because a lot of producers were fed up with the drummers playing too much in the studio.”

To some extent, this focus on simpler drum parts comes back to the fact that by 1975, Clinton’s production style was getting slicker. “By the time we get to mid-70s to late 70s, they're trying to simplify the drum parts to make more room for the singers and the horns and the song in general, and for the charts,” says Bedrosian. “George didn't care about the charts too much until he started landing all over them, you know? And then it's like, ‘Okay, well, we have to think about this.’”

George Clinton did Star Wars before Star Wars

If you listen to R&B or disco bands from the late 1970s, they're all doing space-themed music, because the arrival of Star Wars in 1977 was a game-changer. But Mothership Connection came out two years before George Lucas's first visit to a galaxy far, far away. So I asked Bedrosian why Clinton was so ahead of his time.

Bedrosian says that some of those bands doing space-themed music were actually copying Mothership Connection, because it had been a platinum album. You see bands like Earth, Wind and Fire and Kool and the Gang having a bit more of a cosmic theme to their songs, in the wake of Mothership Connection's undeniable success.

Of course, Sun Ra had been playing Afrofuturistic music with space themes before 1975, and Bedrosian says this was a huge influence on Clinton. Charles Earland had recorded his classic album Leaving This Planet in 1974. And Screaming Jay Hawkins had also played with spacey themes.

Stepping into some big shoes

Finally, I had to ask Bedrosian about becoming the keyboard player for Parliament-Funkadelic — inheriting a tradition that includes not just Worrell, but also people like Joel “Razor-Sharp” Johnson, David Spradley and the legendary Joseph “Amp” Fiddler.

“It's an absolute honor,” says Bedrosian. “You know, I was classically trained ever since I was 3, and my parents were concert pianists. They ran a piano school out of the home. So I had a very similar upbringing to Bernie [Worrell].”

He adds, “Classical music is still the main thing that I do. I still do a multi-hour classical regimen every morning.

It's very much the foundation of what I do. It's the most important thing in my musical day. And Bernie was no different.”

Bedrosian thinks Worrell saw this in him at a young age, and that’s why Worrell chose him as a protege. “I studied under him for several years as his protege, because I think he saw so many parallels.”

And by the time Bedrosian actually joined Parliament-Funkadelic, he’d been studying their music for over a decade, “giving it the real study that a classical musician would give classical music, you know? Over and over, dedicated, dedicated, and learning not just the original [version], but the way every subsequent keyboard player would play the parts.” He also learned to play the horn parts, guitar solos, and bass solos, and even vocal parts for the songs.

“A lot of people think they can just get into a band and not know the music,” says Bedrosian. “You have to know it better than the fans. You have to know it better than half the band to get in.” And given the depth of P-Funk’s back catalog, it pays to have a comprehensive knowledge, because you never know what obscure gem George Clinton will throw at you.

Bedrosian’s books, Make My Funk the P-Funk and The Ultimate P-Funk Song Reference, are available everywhere.