Friends!

Last week I rambled out loud about web components and how their true magic lies in extending HTML. Heck, Jeremy even called them “HTML web components” in a blog post which feels like the perfect framing for them.

You might have noticed how I’ve written several hundred words about the subject already and have not once mentioned Shadow DOM, slots, or templates. And that’s because before we get to styling our web components or making anything more complicated we have to sloooowly build up to all that stuff. Otherwise we’re bound to repeat what happened to me when I started learning about the styles of web components before I understood the philosophy behind it all.

Thus ensued a mid-life crisis that I'd rather not talk about.

So today let’s start with this fantastic piece by Eric Meyer called Blinded by the Light DOM. In his post, Eric creates a humble slider where you can change the font-size of some text:

<super-slider unit="em" target=".preview h1">

<label for="title-size">Title font size</label>

<input id="title-size" type="range" min="0.5" max="4" step="0.1" value="2" />

</super-slider>

And elsewhere in his markup he has the following HTML:

<div class="preview">

<h1>This is a title</h1>

</div>

Here Eric has a custom web component called <super-slider>. That target attribute finds the preview element and then when you play around with the input it’ll change the font-size of the h1 inside.

Here’s the script, which I think is super interesting:

class superSlider extends HTMLElement {

connectedCallback() {

let targetEl = document.querySelector(this.getAttribute('target'));

let unit = this.getAttribute('unit');

let slider = this.querySelector('input[type="range"]');

slider.addEventListener("input",(e) => {

targetEl.style.setProperty('font-size', slider.value + unit);

});

}

}

customElements.define("super-slider",superSlider);

Now you might notice that there’s one thing that I got wrong last time. I mentioned that you have to have something like this in your barebones web component script:

class SpookyButton extends HTMLElement {

constructor() {

super();

}

connectedCallback() {

// magic goes here

}

}

customElements.define('spooky-button', SpookyButton);

But Chris Krycho thankfully wrote in saying that’s not the case at all. You don’t need the constructor or super() function in the vast majority of cases when you’re making a web component.

So, with that, the building block of a web component looks like this instead:

class customElement extends HTMLElement {

connectedCallback() {

// set variables, create functions, make magic

}

}

customElements.define("custom-element", customElement);

Just a bit simpler and just like Eric showed above: you make a class, do almost everything in the connectedCallback function, and then you define your custom element so that the browser can grab the HTML like <custom-element> and apply your customElement class to it. That sounds like a lot! But compared to what we’d have to do in the past this is wondrously simple stuff.

In fact, Adam Stoddard mentions in Step into the light (DOM) that this stuff alone is fantastically helpful:

Vanilla javascript always felt spaghetti-ish in my clumsy hands, but there’s only one way to write custom elements. There’s no making a custom element without writing it as a class. For me, it’s meant an overall improvement in code quality.

Now, here’s where things get weird. Sure, you can wrap markup with a web component and I strongly feel like that should be the default. But when we’re making a web component we don’t have to put any HTML inside at all, like this:

<thanksgiving-button></thanksgiving-button>

See how there’s no HTML elements in there? Lots of web components are like this, although it makes me feel ikcy for reasons we'll get into in a bit. But let’s walk through more of it before we get all judgey.

We want our custom element here to wish folks a happy thanksgiving and we can do that from within our JavaScript instead of our markup. First off we can create a template, like this:

const template = document.createElement('template');

template.innerHTML = `<button>Happy Thanksgiving!</button>`;

This is where we could put any markup that we want. Then, inside our web component itself we append the template...

class ThanksGivingButton extends HTMLElement {

constructor() {

super();

this._shadowRoot = this.attachShadow({ 'mode': 'open' }); this._shadowRoot.appendChild(template.content.cloneNode(true));

}

}

customElements.define('thanksgiving-button', ThanksGivingButton);

(I think I have to use the constructor() here since I’m setting this. But also there are no good blog posts out there explaining any of this stuff and so I challenge you, nay dare you, to really explain all this to me).

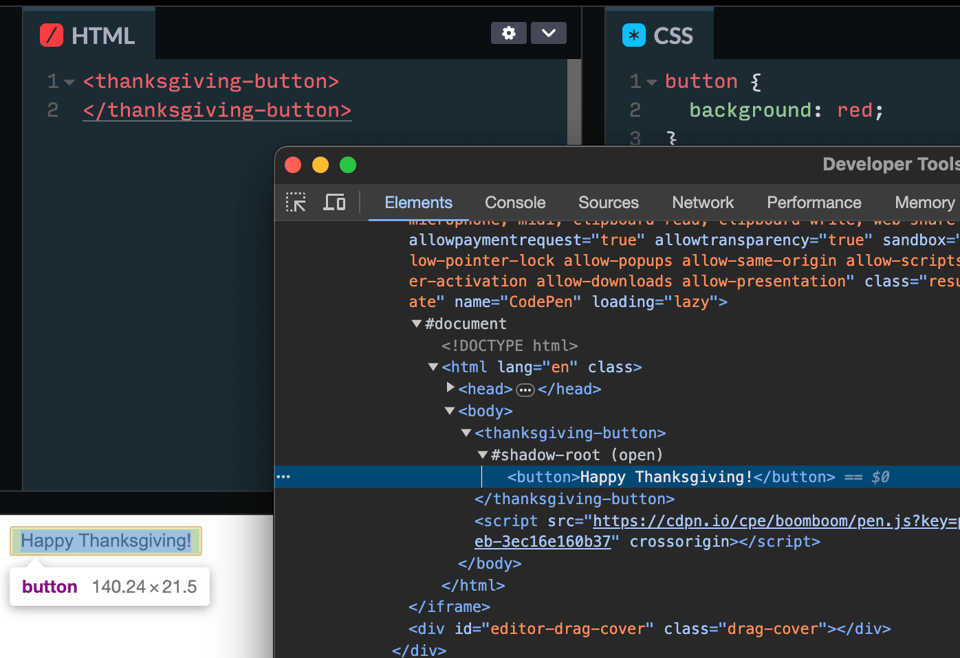

But what we’re doing here is defining what’s known as the Shadow DOM. What this means is that when I inspect the HTML here I’ll see the following...

The text doesn’t really live in the regular ol’ DOM where you’d find all your other HTML elements but in a separate, second place. It’s hidden away from the rest of our markup and shown there in the inspector as the #shadow-root.

An element on the page that is not really an element! That’s neat, although kinda odd.

But when I first used the Shadow DOM I got a bit confused because when I wrote this line of code here in my web component script...

this._shadowRoot = this.attachShadow({ 'mode': 'open' });

...I half expected that this would enable all outside styles AND scripts from being able to peek inside my component. Closing this off would be handy if I want to drag in a web component to a big web app and be 100% certain that nothing goofy happens. This is what I originally thought the whole point of web components was: protected little islands of code.

Instead, that line only disables/enables JavaScript from “peeking” inside our web component.

So if, outside our web component, we write something like this:

console.log(document.querySelector('thanksgiving-button').shadowRoot.innerHTML);

Then in the console we’ll see:

"<button>Happy Thanksgiving!</button>"

But if I “close” my web component off...

this._shadowRoot = this.attachShadow({ 'mode': 'closed' });

...then that console log will absolutely scream at me:

Uncaught TypeError: Cannot read properties of null (reading 'innerHTML')

Sure, okay. That makes sense. But then why doesn't this 'close' off styles, too? Shouldn’t it work all the same?

Ugh, okay. Let’s stop talking around styling web components and just jump right in and be confused together. Because there are many weird and unexpected things about styling a web component.

Let’s start again and go back to our button:

<thanksgiving-button>

<button>Happy Thanksgiving</button>

</thanksgiving-button>

The button element inside is what's known as the Light DOM and I hate that word and refuse to ever use it again. But if you have HTML in that web component like that and try the following styles:

thanksgiving-button button {

background-color: blue;

}

This will work! The color of your button will be blue! This is good! Heck, the styles will also be inherited, like this:

body {

color: red;

}

thanksgiving-button button {

color: inherit;

}

The <button> example here is a bad example since they have default styles and you have to override em, but the point here is that you can change your web component with regular ol’ CSS in exactly the same way you’d expect from styling any other HTML element. There’s no magic, it’s just HTML and CSS working as expected.

You can even style your web component just like a div...

thanksgiving-button {

background: red;

padding: 30px;

}

And that’ll behave just as expected. A big weird red box will appear, just like if you were to style a div.

But now let’s return to that Shadow DOM example from earlier where we used templates to import a HTML button into the web component (wow those sure are words I just typed, huh):

const template = document.createElement('template');

template.innerHTML = `<button>Happy Thanksgiving!</button>`;

class ThanksGivingButton extends HTMLElement {

constructor() {

super();

this._shadowRoot = this.attachShadow({ 'mode': 'open' });

this._shadowRoot.appendChild(template.content.cloneNode(true));

}

}

customElements.define('thanksgiving-button', ThanksGivingButton);

So if you remember, our markup looked like this too:

<thanksgiving-button>

</thanksgiving-button>

Now our CSS won’t work at all...

thanksgiving-button button {

background: red;

padding: 30px;

}

When it comes to the Shadow DOM, all our styles are somewhat encapsulated.

But then in my brain I’d expect it to work because we have ‘opened’ our shadowRoot in JavaScript. That just feels backwards to me, currently. I can imagine sometimes there being a need to have components that are fully editable from CSS outside — say theming or something, and other times I want a fully encapsulated component where neither script nor CSS nor space nor time leak inside.

Okay, that’s fine. Can anyone else hear screaming? Just me? Okay. Let’s continue.

To style our hidden HTML from within our web component we can add a style tag to the template inside our JavaScript:

template.innerHTML = `

<style>thanksgiving-button button { background: red; }</style>

<button>Happy Thanksgiving!</button>

`;

This...won’t work! We can’t select thanksgiving-button like this and instead we have to use a strange CSS selector called :host, like this:

template.innerHTML = `

<style>:host button { background: red; }</style>

<button>Happy Thanksgiving!</button>

`;

Now that works! :host let’s you access elements with CSS from within the Shadow DOM. Okay, got it. By default the :host is an inline element so I expect every web component in the world is going to have something along the lines of this inside:

:host { display: block; }

So there is another way to tweak styles from within a web component with this thing called part. The idea is that from within your web component you can open up bits of components to be styled by global CSS. Let’s say we wanted the button from within our thanksgiving-button to be editable via outside CSS, we can write something like this:

template.innerHTML = `

<button part="button">Happy Thanksgiving!</button>

`;

Now with CSS outside this web component we can access it like this:

thanksgiving-button::part(button) {

background: red;

}

Okay, that makes some kind of sense but also I can now see the screaming.

I guess in a perfect world, I would almost always avoid Shadow DOM – all this complexity is what’s led folks like Chris Coyier to argue that “Shadow DOM is not a good default” or Dave Rupert mentioning that “styling is the least fun part of web components.”

But! I do want to write my web component like this...

<thanksgiving-button>

<button>Happy Thanksgiving</button>

</thanksgiving-button>

...and yet have all those styles isolated in some way. I don’t want button styles leaking in, nor do I want button styles inside leaking out. If I could simply encapsulate styles here then I would barely ever need the complexity of all this template stuff and writing HTML with JS and Shadow DOM which feels sickly to me anywho and overly complex.

Encapsulating styles is a developer convenience, but it feels like all this Shadow DOM stuff actually continues the trend of giant JavaScript libraries: I now have to decide between the developer convenience of isolating my styles with Shadow DOM without good accessibility options OR choose to have a web component that will have a nice HTML fallback BUT is a bit annoying when it comes to styling it and copy/pasting it into other codebases.

Phew. I gotta take a breath for a bit because this knocked the wind out of me.

I guess ultimately I’m not pitching alternatives here, but I wish it was an attribute or a single value I could set in JavaScript that opens/closes my component and still preserves the nicely-wrapped markup. I want Light DOM with the Nice Stuff from Shadow DOM but Without the Complexity Of All That Template Stuff.

Okay, I’m sure all of that made little to no sense whatsoever because at this point I have become the screaming.

See you in the cascade,

Robin

You just read issue #6 of The Cascade. You can also browse the full archives of this newsletter.