New Year’s Eve will never be the same. On December 31, 2019, my wife Grace and I were hosting friends at our home in Connecticut, playing board games with their kids and clinking glasses at midnight to mark the arrival of a new decade. We celebrated in cheerful oblivion of a New Year’s Eve announcement from Wuhan. Earlier that day, the city’s health commission issued a public notice of a small outbreak of viral pneumonia.

“So far the investigation has not found any obvious human‑to‑human transmission,” the commission declared.

In fact, a few doctors around Wuhan had already concluded that this was exactly how the new coronavirus was spreading. “At the end of December, the signs of human‑to‑human transmission were already very obvious,” Zhang Li, a doctor at Jinyintan Hospital later recalled. “Anyone with a little common sense could reach that assessment.” With some help from modern transportation, human-to-human transmission then spread Covid out of Wuhan and around the world. It became the worst pandemic crisis in modern history.

This week marks the fifth anniversary of Covid’s official debut. Since it emerged, the disease has killed perhaps over 27 million people. In 2020, Covid became the third highest cause of death in the United States, trailing only cancer and heart disease. It held onto third place in 2021, slipping to fourth place in 2022. In time, vaccinations and immunity from previous infections made Covid less deadly. In 2023, it slipped to tenth place in the list of U.S. deaths.

But that does not mean Covid disappeared. In 2023 alone, 49,932 Americans died of Covid. That’s a far higher toll than seasonal influenza’s damage in a typical year. And some Covid survivors struggle for months or years to recover. By one estimate, over 400 million people worldwide have endured Long Covid, the cumulative number continuing to climb each month.

I’ve been learning about epidemics for decades as part of my job. When disease-themed movies like Contagion came out, I encouraged people to think of them not just as science fiction, but also as possible futures. But I had never lived through something like Covid. And now, when I look back at photos from New Year’s Eve 2019, it’s clear that I couldn’t really comprehend a Covid future. I couldn’t conceive of just how fast a new pathogen could sweep the planet, or how much chaos it would cause, or how much it would reveal about our scientific advances and dysfunctional public health systems, or how deep a mark it would leave on our collective psyche—even as people did their best to forget that Covid ever happened.

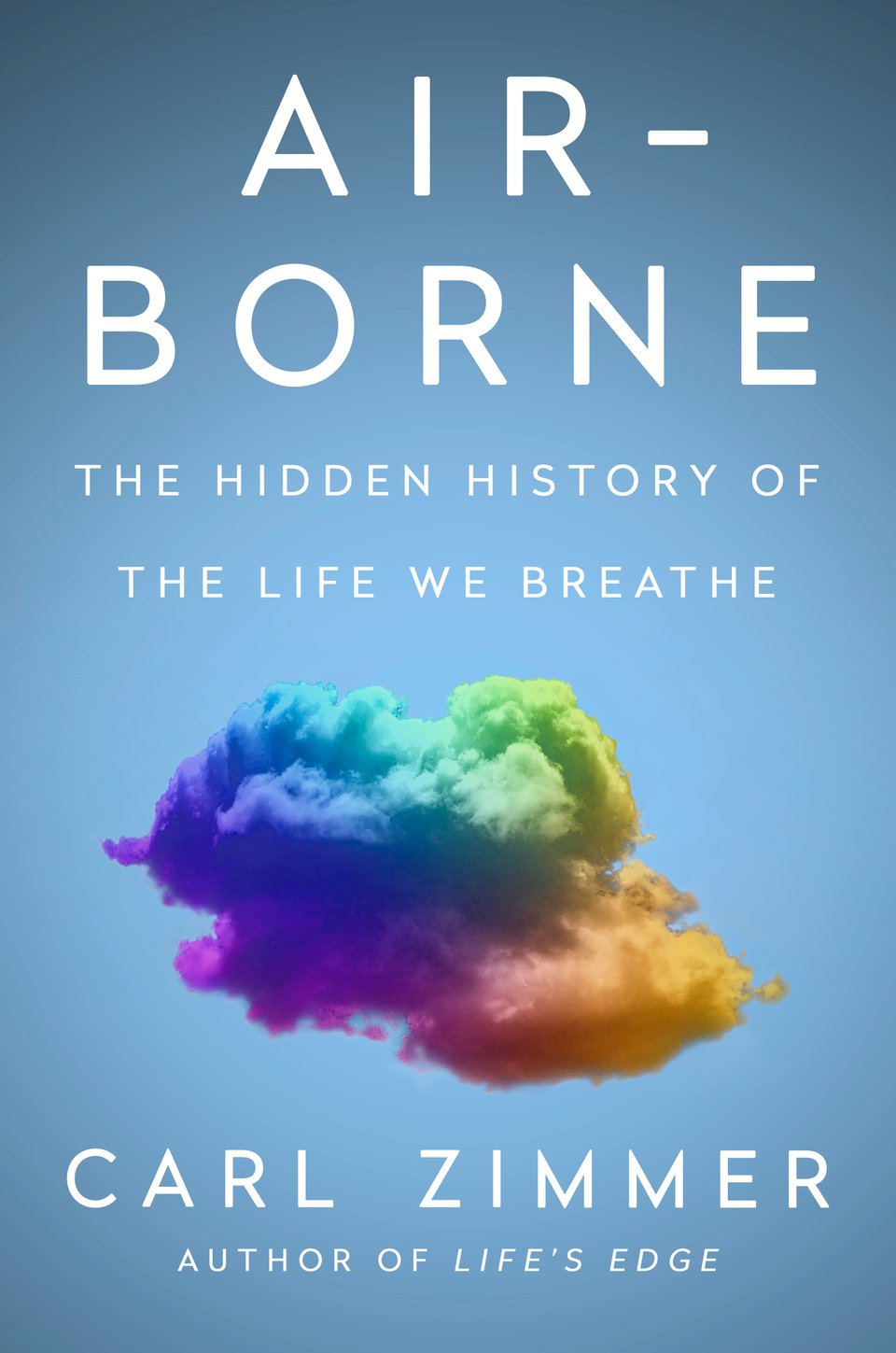

As 2025 unfolds, I’ll have more thoughts to offer here and elsewhere about the fifth anniversary of the news from Wuhan. And when my book Air-Borne comes out next month, I hope it will help, at least a little, to keep us from forgetting too much.

A Mirror Pandemic

Since my last newsletter, I’ve published a couple non-Covid pieces for the New York Times that seem to have hit a couple nerves.

The first is a piece on another pandemic of sorts [gift link]. But it’s a pandemic that cannot happen today. It will only be able to happen if scientists work hard for years to make it possible.

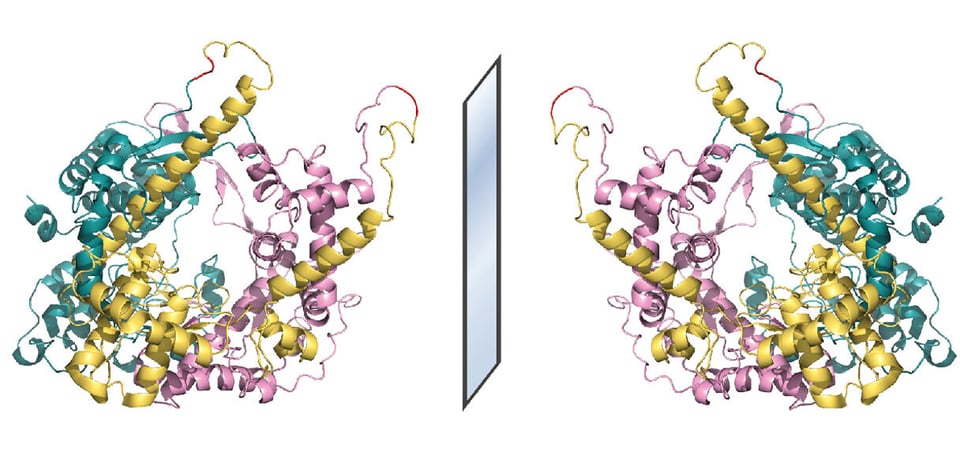

In recent years, researchers have been building proteins and RNA molecules that are mirror images of their natural versions. It now looks increasingly likely that scientists could someday assemble the mirror ingredients required to create an entire living mirror cell.

But as tantalizing as that achievement may be, a group of prominent scientists from many disciplines—microbiologists, immunologists, plant biologists, and others—have decided the risks far outstrip the possible benefits. A mirror cell might, they argue, become an unstoppable pathogen, infecting every species of animal and plant on Earth and disrupting entire ecosystems.

The scenario they offer is so stark that it reminded me of Ice-Nine, the apocalyptic water-freezing molecule of Kurt Vonnegut’s novel Cat’s Cradle. Of course, that was fiction. But the scientists I interviewed for my story think that mirror cells could readily become nonfiction. Before this warning, some researchers on the team were actually doing research that could lead to mirror cells. They have now stopped that work. And they hope the world will find a way from preventing anyone from creating mirror cells.

The Information Trickle

Before the holiday break, I came across a piece in the journal Neuron with a beguiling title: “The unbearable slowness of being: Why do we live at 10 bits/s?”

The piece comes from two Caltech neuroscientists, Jieyu Zheng and Markus Meister. It had its origin in a class Meister teaches on the brain. He wanted to give his students some basic numbers about how the brain works. If he had been teaching a class on the circulatory system, he might describe how many gallons of blood the heart pumps each minute. In the nervous system, information flows instead of blood. Meister realized no one had come up with a good estimate of this throughput, and so he and Zheng used the results of experiments and competitions to estimate the rate at which information is encoded in memory or carried forward to do things like talk or type. A dozen separate estimates converged on a remarkably tiny number: ten bits per second.

I wrote about the unbearable slowness of being for the New York Times last week. [Gift link] (The Transmitter also published an interesting Q&A with Zheng and Meister.) The story elicited a lot of comments, and I am still getting emails about it a week later. And a lot of these responses are downright angry.

Some people object to using information theory in neuroscience. They say that it’s fine to measure bits per second in a computer but not in a brain, because our brains are not computers.

Information theory is not limited to computers. Indeed, Claude Shannon laid down its foundations in the 1940s, and one of the key cases he worked over was the good old English language. You can use his ideas to calculate how many bits it can transmit (roughly one bit per character, it turns out). And neuroscientists have been using information theory to study the brain for decades now.

Other readers questioned whether Zheng and Meister had missed some hidden bits. One reader observed to me that the early cell phone networks needed several thousand bits per second to transmit the speech of callers. When we speak, we must be transmitting thousands of bits per second, right?

I shared this comment with Meister. He pointed out that there’s a difference between a channel’s information rate and its capacity. To illustrate this point, Meister reached back in history before cell phones, to the old-fashioned land-line telephone.

“It was designed to transmit human voice,” Meister told me. “But much later it was found you could use it for dial-up modem connections.” In fact, those old analog phones proved able to transmit 56,000 bits a second.

“Obviously we can’t create the screeching and hissing sounds needed to communicate like a modem,” Meister said. Instead, we use phones to transmit spoken words, which turn out to have an information rate of around 10 bits per second.

There's no doubt that our brains are amazing in some ways. But that amazingness can make it hard for us to recognize the boundaries of their performance. Imagine what the world would be like if we were chirping at each other like modems…

The argument that Meister and Zheng are making is just that—an argument. In the years to come, I will not be surprised to see other neuroscientists take issue with some or all of it. If you’d like to engaged with their argument directly, Meister has posted a pdf of the paper here.

The Air-Borne Book Tour

We’re less than two months from the publication of Air-Borne. Early reviews are coming in. Booklist gives it a star, along with these kind words: “Breathtaking facts plus superior science writing equals engaging, essential reading.”

If you live in or around New York, I hope you can join me and Jad Abumrad, creator of Radiolab, for an Air-Borne launch-day celebration at 92NY. I’ll be signing books after our talk. Details here.

Here are the other events I have lined up, with more to come:

February 26, 2025, Boston. Harvard Science Book Talk/Harvard Book Store. Details here.

February 27, 2025. St. Louis. St. Louis Library. Favorite Author Series. Details here.

March 3, 2025. Online. The Commonwealth Club. Details here.

March 4, 2025. Westport, CT. Westport Library. Details to come.

March 6, 2025. Madison CT. RJ Julia Bookstore. Details to come.

March 19, 2025. Online. Atlanta Science Festival. Details to come.

March 28, 2025. Powell’s City of Books, Portland, Oregon. In conversation with writer Ferris Jabr. Details here.

April 9, 2025. New Haven, CT. Yale University Book Talk. A conversation with biologist and writer Brandon Ogbunu. Details here.

April 10, 2025. Online. The Smithsonian Institution (virtual event). Details to come.

April 24, 2025. Frenchtown NJ. The Frenchtown Bookshop. Details here.

April 26, 2025. Montclair NJ. Montclair Literary Festival. Details to come.

___

That’s all for now. Best wishes for a happy, safe 2025!

You just read issue #182 of Friday's Elk. You can also browse the full archives of this newsletter.