Welcome to another edition of "Friday's Elk." I'm settling down here at my new home at Buttondown and hope to send this newsletter out on a fairly frequent basis. It'll stay free, but any support will be much appreciated!

X Marks Many Spots

It's been so long since I learned about the X chromosome that I can't remember when I became aware of it. It's one of the first things we learn about genetics, because the basics are so basic. We have 23 pairs of chromosomes, 22 of which are identical. The 23rd pair are the sex chromosomes: in females, two X's, and in males an X and a Y. Done.

It wasn't until much later that I learned the X chromosome hides a marvelous mess of complexity and raises all sorts of interesting questions about what is the best way for biology to work.

There are some 900 genes on the X chromosome. All things being equal, a woman's two X chromosomes should produce twice as many proteins from those genes as the genes on a man's one X. But that's not what happens.

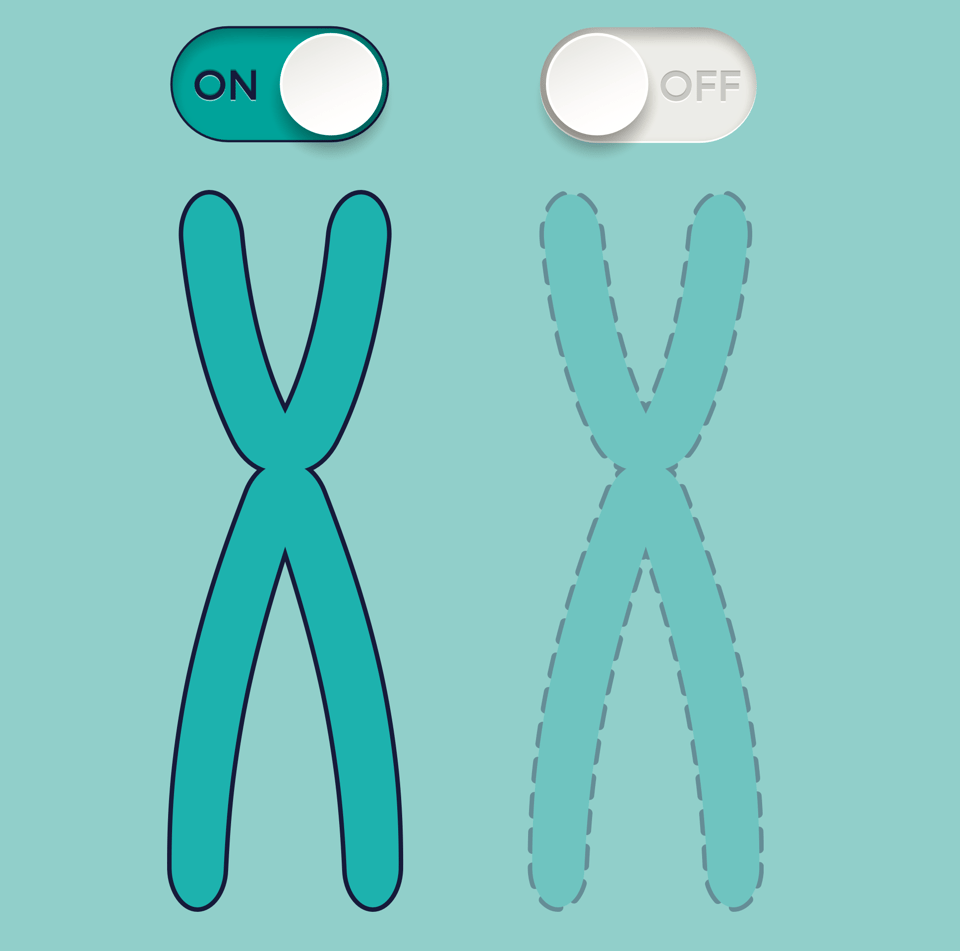

Thanks to a remarkably complicated system of molecules, one X chromosome in every cell is silenced. Almost all of the genes on the second X chromosome can't make their proteins. As a result, women produce about the same amount of proteins from their X chromosomes as men.

The system that silences the second X is crazily complicated. It starts with a molecule of RNA called Xist that's 19,000 bases long. That alone is ridiculous. Then a bunch of proteins stick to it, and then they grab onto the X chromosome and initiate all sorts of reactions that block the genes on the X from making proteins. Scientists are still working out all the details, and when I ask them to walk me through the latest understanding, my head is alway left spinning.

Keeping this balance seems to be very important: too many X proteins can be toxic to a cell, and may even contribute to diseases like cancer. But the elaborate system that silences the X chromosome inflicts a pretty steep price for its services. In the New York Times yesterday, I wrote about how the X-silencing proteins may confuse the immune system, leading to auto-immune diseases. That confusion may help explain why 80 percent of people treated for auto-immune diseases are female.

This may turn out to be an inescapably bad deal for people with two X chromosomes. (That includes people who have two X's and one Y, a condition known as Kleinfelter syndrome.) But X chromosomes also cause problems for those with only one copy. If a man carries a harmful mutation in a gene on his X chromosome, he does not have a working back-up of the gene on another X chromosome. As a result, a number of dangerous hereditary diseases such as muscular dystrophy strike mostly males.

Just because the X chromosome is at the heart of human biology does not mean that all this suffering is an inescapable rule of nature. Things didn't have to turn out this way. If you look at other species with sexual reproduction, they don't have our particular trouble. My favorite example is flies. Their chromosomes are strikingly similar to ours. Their sex is determined in much the same way: two copies of a fly version of X leads to the development of a female. An X and Y leads to a male. But the female flies don't even things out by silencing one X chromosome.

Instead, it's the male flies that do the compensating. They rev up their one X chromosome so that it doubles its production of proteins. The system male flies use to reach this balance is wonderfully baroque in its own right. Since flies don't go to doctors, we don't have a good sense of whether the males suffer from various ailments as a result of X-chromosome overdrive. But it wouldn't be surprising if they did.

While that may remain unclear, what is abundantly clear is this: our particular X chromosome woes are the result of a less-than-perfect solution, one of many that have evolved along the tree of life.

DNA on the Daily, and Tales of Wandering Mammoths

On Wednesday, I spoke to Sabrina Tavernise on the Daily podcast about my recent article on ancient DNA and modern medicine. You can listen to it here.

I also wrote a story about how scientists reconstructed the life and travels of a mammoth that lived 14,000 years ago. You can read it here.

That's all for now!

Best wishes, Carl

You just read issue #166 of Friday's Elk. You can also browse the full archives of this newsletter.