The Sisyphus Tree

With just two days left in 2023, I have been looking back over the year in biology, scanning for news that pops out.

There were some stories of long-dreamed triumphs. In late 2023, both the United States and the United Kingdom gave the green light to CRISPR as a medical treatment for the first time.

Back in the 1990s, CRISPR first came to light as a kind of immune system for bacteria. The microbes made molecules that zeroed in on viruses, shredding their genes. Scientists converted those molecules into a tool for editing DNA in human cells. With CRISPR, researchers rewrote genes in the blood cells of people with sickle cell anemia and other blood disorders, reversing their diseases. Newer forms of CRISPR may very well cure other diseases in the years to come. (Here is a piece I wrote for Quanta and another for the New York Times, both on the history of CRISPR.)

This year was also full of buzz about A.I. The headlines were mostly about how it may alter human experience, from waves of plagiarism in college to rampant unemployment in the knowledge economy. The explosion of A.I. news in 2023 could leave the impression that it barely existed beforehand. But scientists have been using it for several years now to make some big advances.

Protein scientists in particular have been having a lot of fun with A.I. They have trained computers to crack the great puzzle of protein biology, known as the folding problem. Protein scientists can now use A.I. to read the sequence of amino acids in a protein chain and predict how it will fold into an intricate three-dimensional shape. In 2023, scientists took a step further, using A.I. to create proteins that nature had not yet produced. In this new universe of molecules may lurk medicines and other important molecules.

These stories are significant and inspiring. But they are not the only ones to be told. For me, one of the most poignant pieces of news in 2023 concerned a stand of stunted American chestnut trees in Indiana.

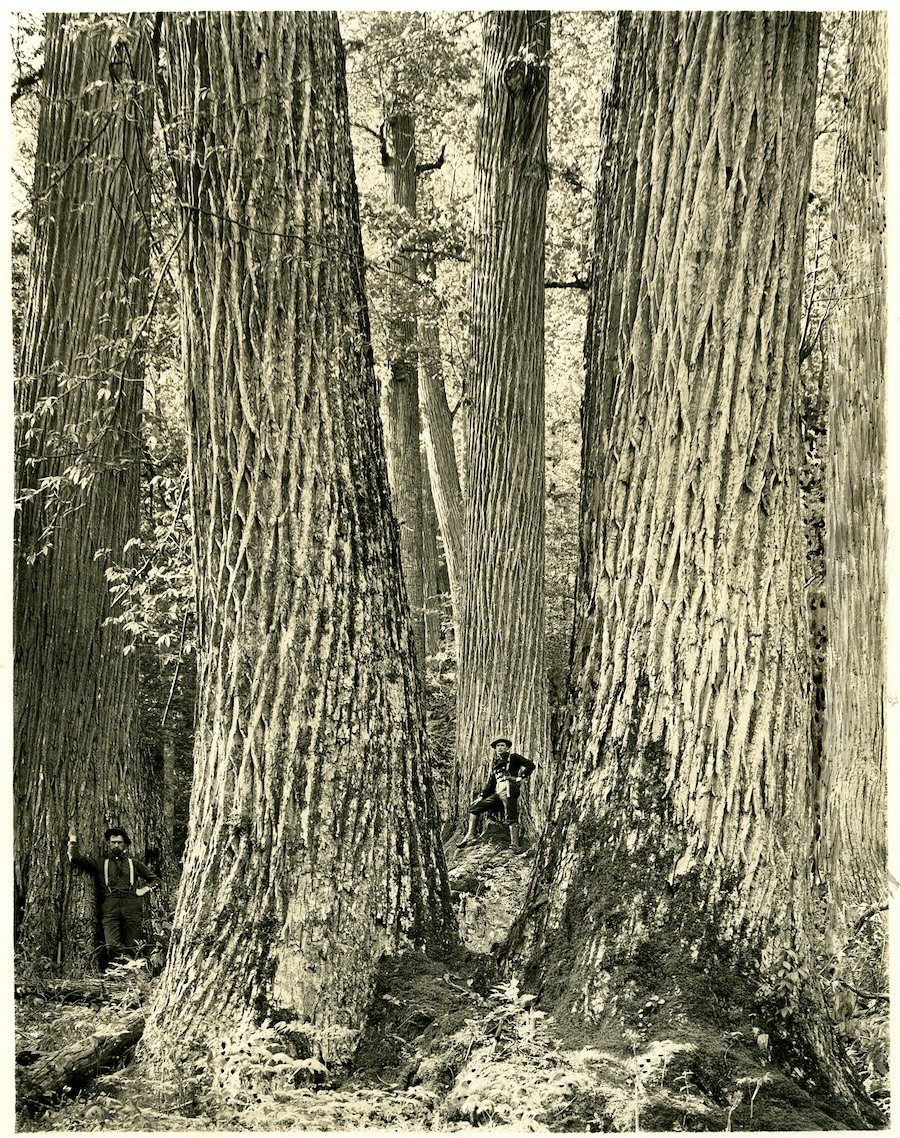

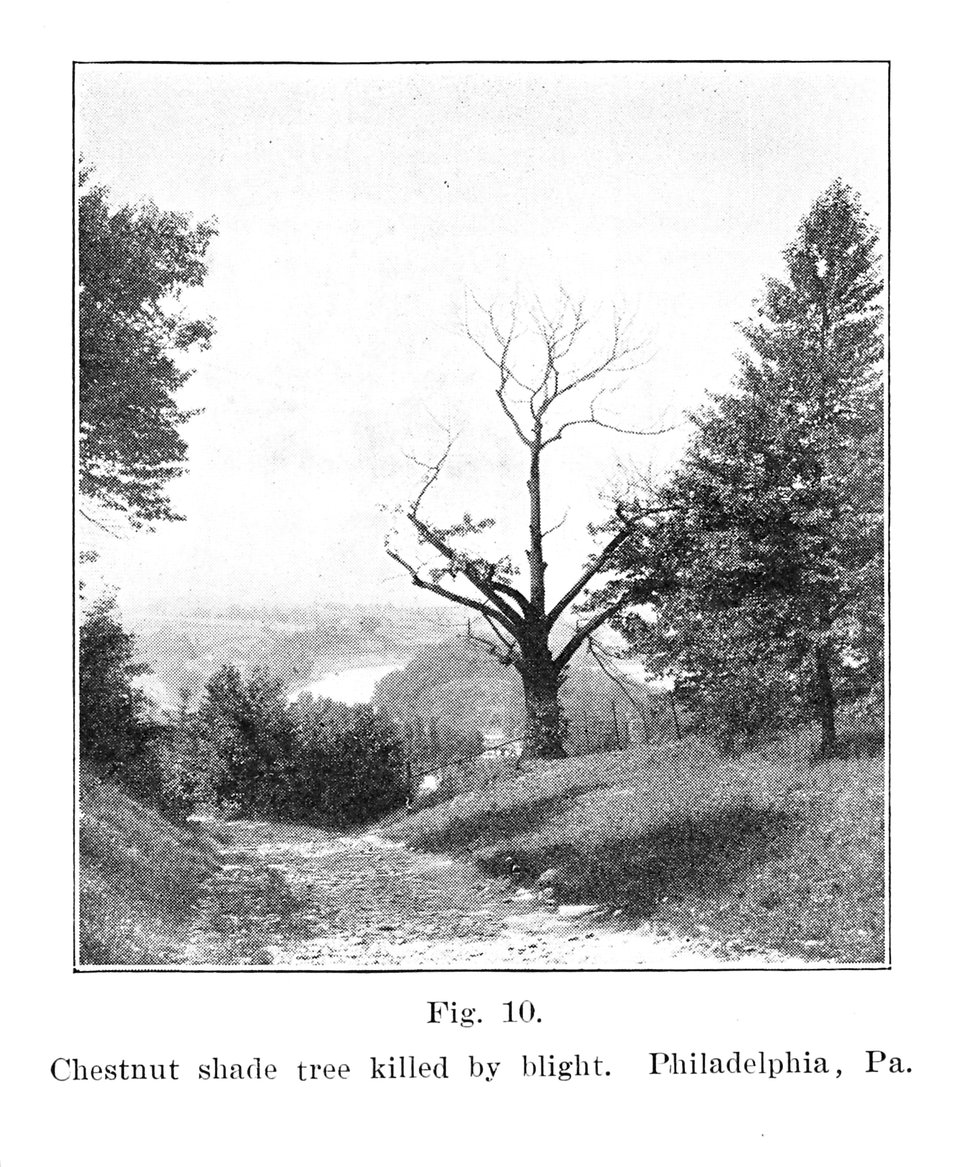

Forests dominated by mighty American chestnuts once stretched across much of the eastern United States. Each summer, their white flowers bloomed so thickly that they made the peaks of the Appalachian Mountains look as if they were capped with snow. But in the early 1900s a fungus called the chestnut blight began killing off the trees. It was likely introduced to the United States in chestnuts imported from Asia. The Asian chestnuts had evolved to hold the blight at bay, but the American species had no defenses. Three billion trees were infected, and their forests collapsed. Today, some American chestnut stumps still survive. The blight cannot penetrate all the way down to their roots. But any shoots the stumps send up are vulnerable to attack.

“They sprout up, they get the blight again, and they are killed down to the ground,” William Powell, a botanist at the SUNY College of Environmental Science and Forestry in Syracuse, New York, told me in 2012. “You know the story of Sisyphus? The guy who rolled the rock up the hill and it just kept rolling back down? Well, that’s kind of like what’s happening with the chestnut.”

When I spoke to Powell, he had spent over 20 years working towards resurrecting the tree. He and his colleagues started their efforts with an enzyme that Chinese chestnut trees uses to stop the blight's growth. Powell and his colleagues tried to endow the American species with the gene for that enzyme, to make it resistant as well.

They started with traditional hybrid breeding, an achingly slow procedure. Later, they were able to isolate the enzyme gene and transfer it directly into American chestnuts. They also tested out other genes that might increase the resistance against blight. Powell team planted a few modified chestnut trees at the New York Botanical Gardens and got to work on trials that would win the trees approval from the U.S. government.

I met Powell at a 2012 meeting in Washington. He joined a group of scientists at the headquarters of the National Geographic Society to talk about a tantalizing concept: reversing extinction with biotechnology. They called it de-extinction. Some of the people at the meeting wanted to reclaim recently vanished species, like the American chestnut or the passenger pigeon. Others wanted to reach back to earlier victims of humanity, perhaps even to revive the woolly mammoth.

I wrote about the meeting in a cover story for National Geographic. Since then, I’ve checked in on de-extinction's progress from time to time. In 2021, for example, I reported on the launch of a flashy new start-up that made de-extinction its business. For an excellent, thoughtful consideration of where de-extinction stands today, a decade after its debut, I highly recommend this essay that Sabrina Imbler published earlier this month in Defector.

Imbler explores some of the big technical advances that make de-extinction more plausible today than it seemed ten years ago. Scientists can now reconstruct the genomes of extinct animals more accurately from museum specimens and fossils. CRISPR now opens the possibility of precisely editing DNA. Instead of building extinct genomes from scratch, scientists could potentially tweak the DNA of living species: give Asian elephants a woolly coat, for example. Reproductive technology is getting more sophisticated too: scientists are getting better at cloning mammals and are making some headway in cloning birds—a far tougher challenge given the shelled eggs they lay.

Along with the how, Imbler also considers the why. Some advocates of de-extinction think it would be cool to encounter species that disappeared in the past few thousand years. Some argue that since we humans are responsible for their disappearance, de-extinction is part of the moral imperative of conservation. And still others maintain that ecosystems will function better—even capturing carbon from the air—if their crucial species are restored.

Imbler isn’t persuaded, calling de-extinction “the epitome of the incorrigible human belief that, with enough money, we can find an escape clause from the destruction we've wrought on the planet.”

As an idea, de-extinction feels wildly mismatched with the scale of the crisis it is meant to address. After a decade, its advocates are still trying to figure out how to revive a handful of species. Let’s say for the sake of argument that Colossal manages to hatch a dodo-like bird in 2030, then rears a flock of them, and then places them on Mauritius, the island where humans wiped out the real dodos three centuries ago. That feat would barely alter the destruction of bird species our species has achieved. Ornithologists have long suspected that humans wiped out several hundred species of birds. This year saw the publication of a new study in which a team of scientists raised their estimate to 1500 species.

And that’s just birds. Humans have also driven reptiles, amphibians, mammals, fish, invertebrates, and plants extinct with habitat destruction, hunting, and shuttling diseases and competitors around the world. And we are just getting started. When the de-extinction crew first met in 2012, the level of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere was 390 parts per million. Humanity has increased its emissions ever since; now the concentration has reached 420 ppm. And now the impacts that climate scientists have been warning us about for decades are here. The climate’s future is full of potential threats to biological diversity including droughts, wildfires, intolerable heat, and flooded coastal habitats.

Some of the tools that de-extinction scientists are building may help protect species that are still around. It may be possible to engineer endangered animals and plants to withstand new diseases, or to tolerate short-term shifts in the climate. But preventing the ongoing extinction crisis from reaching its full potential will require more than tinkering with one species at a time. Reviving the dodo with CRISPR may seem bold. But dedicating half the Earth to wildlife and bringing carbon emissions to zero are bolder.

In November of this year, William Powell died of cancer at age 67. He did not live to see his American chestnuts thriving in the wild again. But he could take some satisfaction in the steady progress he and his colleagues had made over his career. When Powell died, it looked as if his transgenic tree--known as Darling-58--was close to getting regulatory approval.

But by the end of 2023, it became clear that the chestnut project had not been progressing smoothly after all. Some of the trees growing on test plots were stunted. The leaves on some were turning brown. It turned out that many of the trees the scientists were testing were not Darling-58. Someone had accidentally introduced a different line of chestnut into the program. Making matters worse, the gene for blight resistance had ended up on the wrong chromosome in these trees. In December, the American Chestnut Foundation decided to pull its support for the breeding project. Its fate is now uncertain.

Reviving the American chestnut tree has long seemed like the most straightforward de-extinction project of all. Scientists did not need to rebuild the tree's genome from scratch, since its living stumps are still with us. They did not even need to invent resistance to blight, since evolution had already done the work in Asia. And yet, after more than three decades, it's hard to say when American chestnuts will thrive again. Powell once likened the trees to Sisyphus. But it’s now the scientists who continue his work who will have to roll the rock back up the hill again.

Looking Ahead

I'm looking forward to writing more issues of "Friday's Elk" in 2024. I'll be working on essays like this one, in which I'll do my best to make sense of the science news that washes over us. If there are things you'd be interested in reading about here, please don't hesitate to reach out.

I plan on keeping "Friday's Elk" free to read. If you'd like to support this work, you can sign up for a subscription at any level you'd like. Thanks to the people who have already signed up. If you encounter any trouble in subscribing, please let me know.

Best wishes, Carl

You just read issue #164 of Friday's Elk. You can also browse the full archives of this newsletter.